Black Bridgewater-area Soldiers, 1775

Remarkable Revolutionary muster roll links forever four Black soldiers and their dogged pursuit of liberation.

Welcome! Friday is Evacuation Day in Suffolk County, Massachusetts. This holiday marks the end of the Siege of Boston that began when the British army’s April 1775 retreat from Lexington and Concord left them bottled up on Boston’s Shawmut Peninsula. The siege ended when Gen. George Washington’s forces armed and fortified Dorchester Heights, demanding the British to evacuate Boston on March 17, 1776. - Wayne

Four Black Soldiers

The document excerpted below is a treasure; it links forever four men and their dogged pursuit of liberation. They are:

Tobey Torbett/Talbot, (West) Bridgewater

Cuff Mitchell/Ashport, Bridgewater

Jupiter Richards, Bridgewater

Cuffy Rosaria, Abington

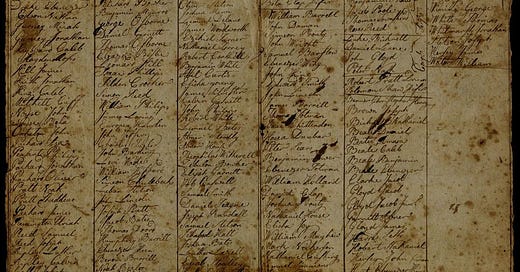

The document is a Muster Roll for the 10 Companies of the 34th Regt of Foot in the Service of the United Colonies 1775, a regiment formed in April 1775 in response to the Lexington Alarm.

This two-page muster roll is an exceptional historical and genealogical resource documenting the names of hundreds of soldiers, primarily hailing from Plymouth County, Massachusetts, who were present during the early days of the Siege of Boston, including at least seven soldiers with African background and one Indian man, Joel Sugmug/Suikamug.1 In recent years, the stories of these soldiers have resurfaced, bringing them into the center of historical discourse.

Below are the compelling stories of four such men.2 Also, take note of the intergenerational-ness of Black military service from colonial times to the Civil War and how it’s an underexamined feature of our local heritage.

Tobey Torbett/Talbot (1st Company)

Tob(e)y Torbett/Tarbet/Talbot’s incredible struggle is well known to those ensconced in local colonial Black history, but it is an extremely offline story. I have little original research about Talbot and rely on parsing two secondary sources, most specifically Mary Blauss Edwards' presentation to the NEGHS titled Black Families of Revolutionary Plymouth County, Mass., summarized here.3 4

Pvt. Toby Talbot endured shocking hardship and violence to keep his family together. Enslaved by Ichabod Keith (d. 1750) in the present-day town of West Bridgewater, Toby was a laborer responsible for clearing land and harvesting pine tar.

Toby married Dinah Goold in 1735, and the couple had eleven children. Chatel slavery being what it is, many Talbot children were sold or given to different households. Toby’s subsequent enslaver, Lydia Williams Keith White Jones, married thrice and moved towns several times. As a result, the Talbot family was, at times, scattered throughout West Bridgewater, North Bridgewater (now Brockton), Whitman (then Abington), and Weymouth.

Toby was constantly advocating to keep his children close and insisted on visitation. This self-advocacy would continue for decades, even after he completed his Revolutionary service.

As we can see in the muster roll, Talbot answered the Lexington Alarm. After that, he mustered in the Bridgewater militia at least two more times and then served as a professional soldier in the Massachusetts line of the Continental Army.

According to Blauss Edwards, Talbot used his service to negotiate his freedom. Although Talbot asserted himself as free after his militia service, Jesse Howard contested Toby’s freedom. In 1779, Talbot negotiated a deal that allowed him to earn wages in the army to purchase his freedom. After his 1780 discharge, Talbot returned from West Point, New York, and attempted to resume life as a free man. Unfortunately, Howard reneged on the bargain, and Talbot had to sue Howard to prove his free status.

During this time, Toby invited his teenage daughters Dinah and Matilda to live with him, but enslavers Elijah Snell and Samuel Dunbar gathered a mob of angry white men who violently broke and entered Toby’s home, assaulted the Talbots, and then kidnapped and re-enslaved Dinah and Matilda.5

Ever the freedom fighter, Toby sued several times for his daughters’ freedom, albeit unsuccessfully. By 1783, the final suit in the Quock Walker case had been adjudicated, accelerating gradual abolition in the Commonwealth; all Talbots were free, with many of the younger children living with their parents. Dinah, perhaps wanting to escape traumatic memories of the Bridgewater/Brockton area, became one of the many Plymouth County Black folks to remove to Maine after the Revolution.

Postscript: Two of Toby’s great-grandsons, brothers Jacob Talbot and John Talbot, served in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry of the United States Colored Troops. The Talbots’ sister Adeline (Talbot) Patterson (Toby’s great-granddaughter) married James Patterson, who served the USCT in the 5th Massachusetts Calvary. This means that Adeline had two brothers and a husband who served in the Civil War. These Talbots and Patterson are buried in Norwell’s historic First Parish Cemetery; although there is no headstone for Adeline, she is presumed to be buried near her husband and brothers.

Cuff Mitchell/Ashport (1st Company)

Cuff Ashport, once known as Cuff Mitchell, purchased his freedom from his enslaver Nathan Mitchell Sr. of Bridgewater, Massachusetts, in March 1775. One month later, news of the Battles of Lexington and Concord spread throughout the countryside and Ashport answered the alarm.

Rich details of Ashport’s biography come from the Revolutionary War pension application filed by his widow, Lydia (Elizabeth Quay) Ashport.6 Impressively, Pvt. Ashport was a party to several historical events.

Stationed in Roxbury, Ashport was likely amongst the men put on alert the afternoon of June 17, 1775, when the Battle of Bunker Hill erupted. Roxbury soldiers reported seeing gun smoke rise above Breed’s Hill, and then later at night, John Trumbull noted:

The roar of artillery fired at—the bursting of shells (whose track, like that of a comet, was marked on the dark sky, by a long train of light from the burning fuze)—and the blazing ruins of the town, formed altogether a sublime scene of military magnificence and ruin. That night was a fearful breaking in for young soldiers, who there for the first time, were seeking repose on the summit of a bare rock, surrounded by such a scene.

Nathan Mitchell Jr., son of Ashport’s enslaver, related that Ashport described being at Dorchester Heights during the British Evacuation of Boston in 1776; another affidavit reveals that Cuff marched from Bridgewater to the City of New York later that year. Deeper into his career as a professional soldier, Ashport witnessed the execution of notorious British spy and Benedict Arnold collaborator Maj. John André.

The Maj. André mention piqued my interest because I wrote about a teenaged Abington soldier at the same event. Here’s an excerpt:

Analyzing this moment, scholar Judith L. Van Buskirk notes in her book Standing in Their Own Light: African American Patriots in the American Revolution, that “[Primus] Coburn was part of a unit that another veteran of color described as a black company. It could be that André’s last glimpse of this world included a group of black soldiers watching his ultimate defeat from a prominent position around the gibbet.”

Postscript: Cuff’s great-grandson Lemuel Ashport was a Civil War veteran of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry; in 1881, Lemuel became the first Black police officer in Brockton.

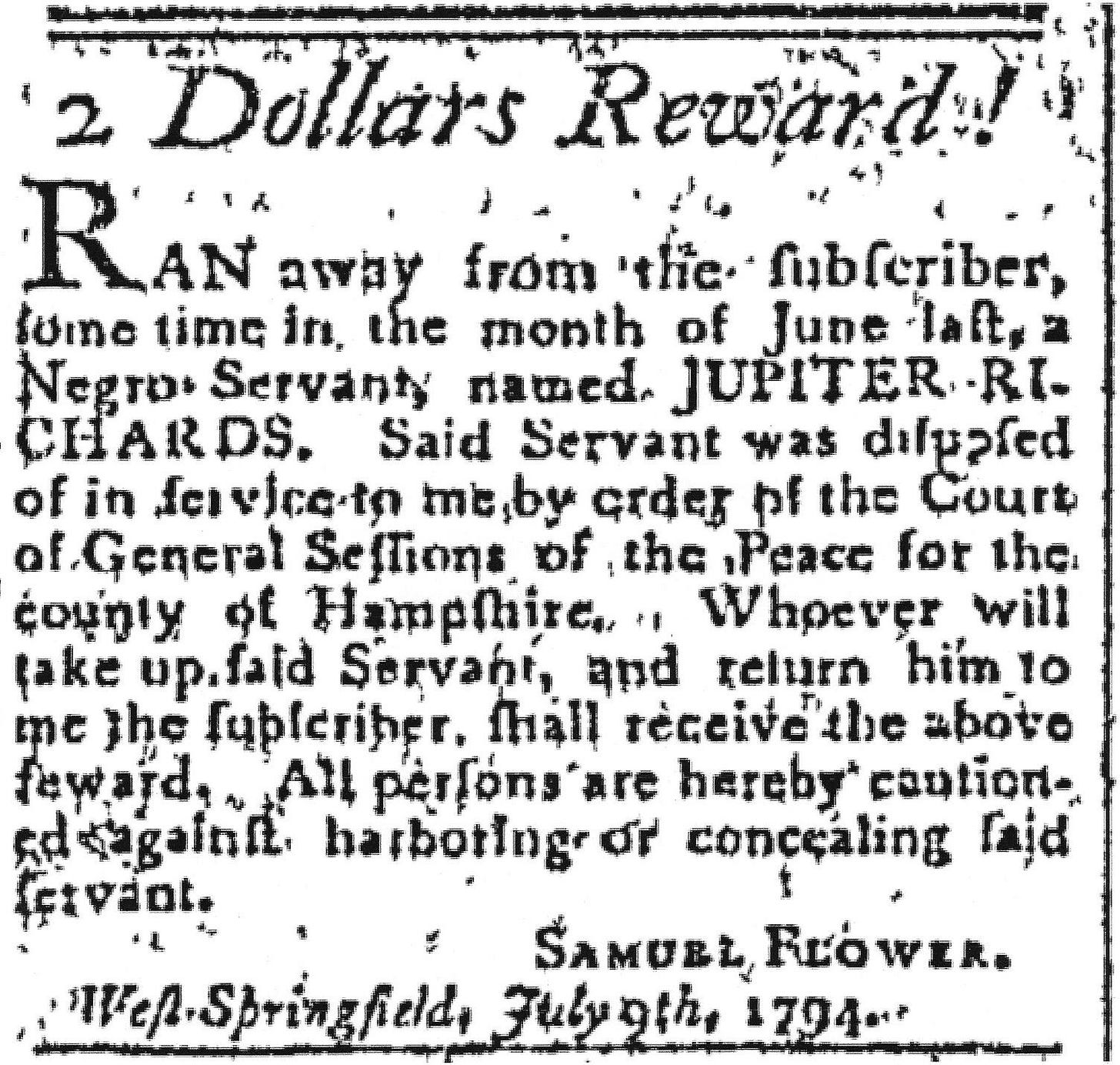

Jupiter Richards (7th Company)

Cliff McCarthy brings us “The Saga of Jupiter Richards” via Freedom Stories of the Pioneer Valley.

Jupiter Richards enlisted in 1775 as an enslaved man, but by 1776 Bridgewater vital records listed him as a “free negro man.” Perhaps answering the Lexington Alarm earned Jupiter his freedom. Richards, a father to young children and newly married, served in the Continental Army from 1777 to 1782, marching first to Western Massachusetts, then West Point, New York, and finally Rhode Island.

Jupiter’s service was unusually long; perhaps Richards did not want to return to Bridgewater. However, McCarthy notes that by 1785 Richards appeared in Springfield, Massachusetts. He was now married to Phillis, formerly the wife of Bridgewater’s Thomas Quacum, and in 1789 Quacum married Jupiter’s ex-wife Lettice Richards.

Richards’ personal life was complicated. But leaving Bridgewater only made Jupiter’s life more difficult. Richards was convicted of stealing three shillings’ worth of rye. He could not pay the fine and court costs, so the court handed down an excessive sentence requiring Richards to be indented to Samuel Flower for twenty years. Flower owned Richards’ labor and Richards would have to follow Flower’s instructions. It sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Richards’ punishment bears a striking resemblance to the Black Codes of the Jim Crow South. Black men and women were arrested on trumped-up, if not outright fictitious, charges and then given harsh sentences to perform free labor at prison farms.

McCarthy’s story is detail-rich and worth the time to read. The final detail of Richards’ life dug up by McCarthy is a 1794 runaway ad posted in Springfield’s Federal Spy newspaper.

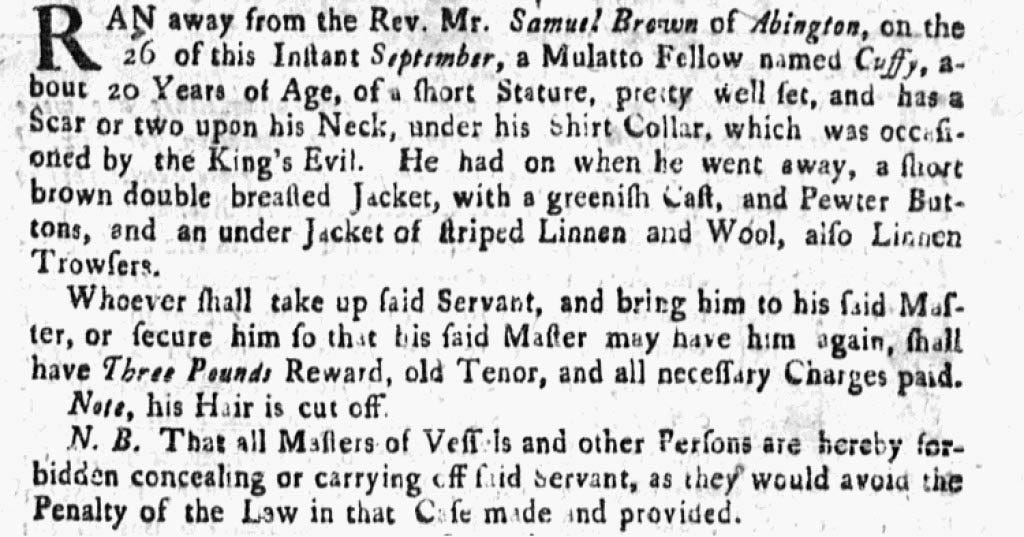

Cuff Rozara/Rosaria (4th Company)

Cuff Rosaria has the distinction of appearing both in a runaway ad and Revolutionary War muster rolls. Enslaved in Abington, first by the Rev. Samuel Brown and then by the brutal Squire Josiah Torrey, Cuffy was a French and Indian War vet and father to Revolutionary soldiers Silas Rosaria/Rosier and Cuffy Rosaria/Rosier, Jr.

The Rosaria name appears with more than twelve different variant spellings. I suspect that Cuffy senior (or his father) originally lived in a Portuguese colony such as Cabo Verde, Angola, or Brazil. Therefore, I choose to use the Rosaria spelling as a nod to local lusophonic communities and to connect their heritage with our nation's founding history.

For an in-depth account of Cuffy Rosaria’s life that includes details of torture he endured while enslaved, acts of resistance and sabotage, and an exploration of how Cuffy may have experienced the Battle of Bunker Hill, see my eleven-names.com story Abington Legend Cuffy Rosaria or the abridged Enslaved soldier’s history sheds light on Mass. Black patriots at the Bay State Banner.

Also appearing on this muster roll is Elias Sewall, a Black man related by marriage to the Sash Family, who we met last week, and the prolifically activist Easton family, who we met in December. Andrew Pomp (Andrew Pompey/Andres Pomp) is a man of mystery; perhaps a different variation of his name will unlock information in the future. Finally, Joseph Nickerson is likely the same free Black Joseph Nickerson enumerated in the 1790 U.S. Census as one of two free Black heads of household in Hanover.

For further reading on Black, native, and multiracial soldiers of the Revolution, check out the essay in the Massachusetts chapter in the DAR’s Forgotten Patriots: African American and American Indian Service in the Revolutionary War and consult the roster of 1,700 names of Black, mixed, and native men. Approximately fifty men of color with Revolutionary service records have ties to Old Bridgewater, which today would also include Brockton, East Bridgewater, and West Bridgewater.

I learned Toby Talbot’s story from Mary Blauss Edwards’ 2021 presentation to the NEGHS titled Black Families of Revolutionary-Era Plymouth County, Mass. (See: 12:47 - 18:01.) See also: Blauss Edwards’ pathbreaking WordPress site, Of Graveyards and Things; her work on early Black and native people in Southeastern Massachusetts has greatly informed my work.

For links to secondary and primary sources, see The Underground Railroad…Across Town: The Story of Toby Talbot [sic] of Bridgewater, Massachusetts.

For excellent summaries of the two Tarbet/Talbot freedom suits, refer to unpublished research from the clear-eyed and ever-helpful Edward L. Bell, (2022) Research Summaries of Massachusetts Freedom Suits 1660–1784 (last revised March 8, 2023.) pp. 133 - 136. online: https://www.academia.edu/76814209

Elizabeth (later Lydia) (Quay) Ashport declares that she was born enslaved in the household of Anthony Winslow. Bridgewater Vital Records concur, and they note in Winslow’s household the presence of Pegg, who died in 1773 at age 60. Also listed is "Anthony Winslow's Negro" Scipio "belonging to [the Continental] army," who died "in ye Summer of 1778,” in Pennsylvania. Additionally, there is a 1764 marriage record where a Scepio marries a Pegge. Three men named Scipio were known to have served in the Revolution for Bridgewater. Scipio Solomon and Scipio Paunce/Ponce were accounted for in 1780. I cannot place Scipio Parmer after February 1778, but I also can’t put him in Pennsylvania in the summer of 1778.

I have 1779 Revolutionary War Col. Wigglesworth Command Dissolution Payroll Scipio Paunce/Ponce

also called Sippe Oponce Sip Ponce Sip O'pome because of troubles with reading hand written documents and names were writen as they called the person! :D