Plymouth Deeds Reveal Activist Origins

The Roots of Sarah and Benjamin Roberts, Hosea Easton, and the Gunderways

Welcome. Would you take a moment to recommend Open Notebook on your social channels or forward this email? Thanks! - Wayne

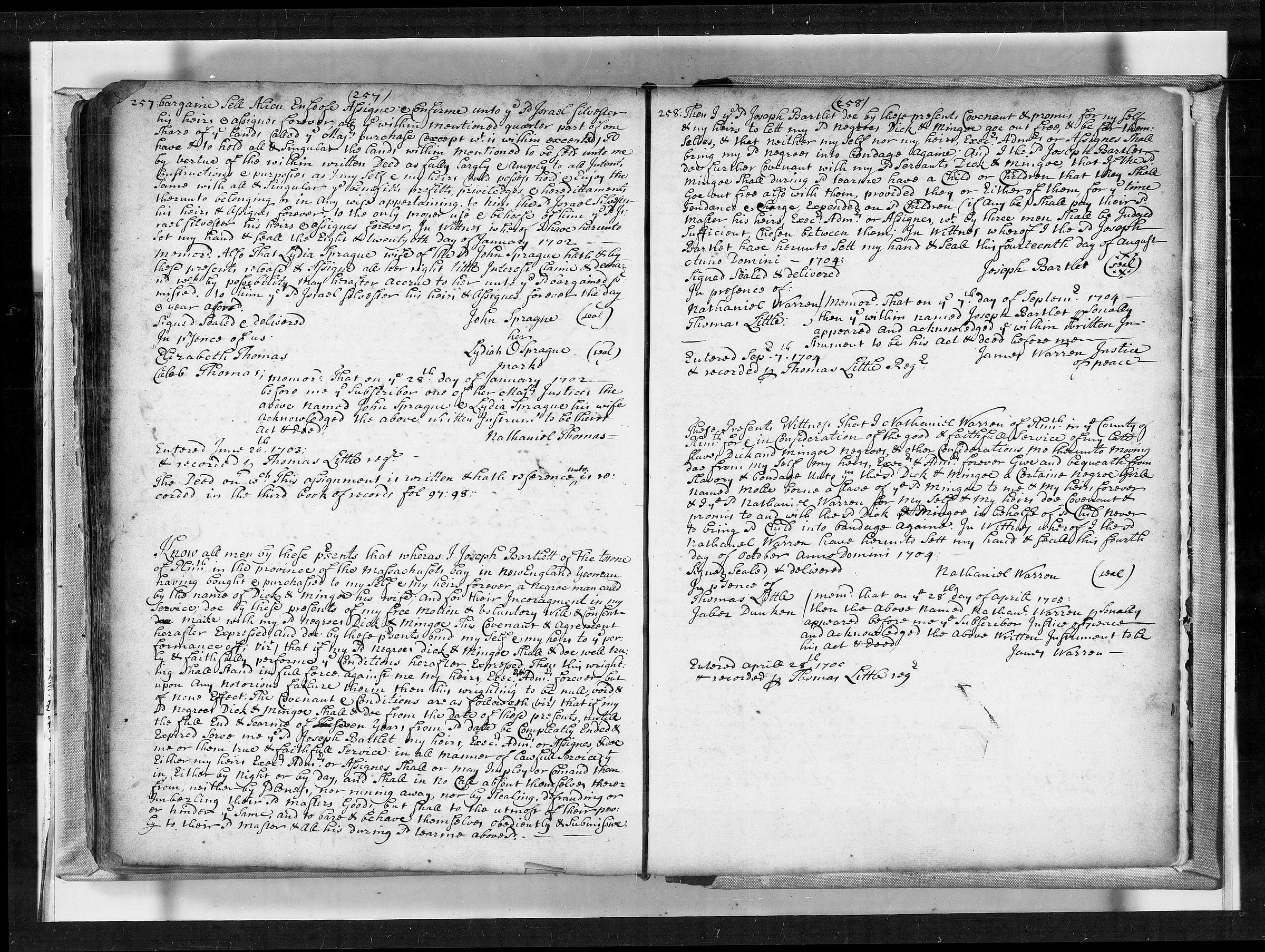

Dick and Mingoe are Manumitted in Plymouth, 1704

The Plymouth County Registry of Deeds—it’s not just for researching old houses. Enslaved people appear in deed books.

Below are the entries for the 1704 manumision documents of Dick and his wife Mingoe of Plymouth, signed by Joseph Bartlett and Nathaniel Warren. Circumstantial evidence suggests that this may be Richard and Mingo Gunderway1, ancestors to the Easton/Roberts family of activists and the Gunderways of South Scituate/Norwell. These families are well-documented, and their descendants are alive today, many still in the South Shore region.

This document also manumitted a daughter named Molle, and I wonder about the line “in Consideration for the good and faithful service of my Cato” that appears in the bottom right paragraph. Perhaps Cato was the father of Dick or Mingo? If so, Cato is the earliest tracable ancestor in this prolific line of activists and fighters.

Next, we find the 1708 baptismal record for the children of Richard and Mingo, servants of Mr. Joseph [illegible]; Margret is noted as being born in 1701, and twins Mary and Marth(a) are born in 1708. Margret and Molle may be two different people, but ‘Molle’ might be the family nickname for Margaret. Then, in 1712, Mercy, daughter of Richard Gundaway was baptized. Although Mingo is not mentioned by name, the name Mercy fits the pattern of the other four female members of Richard and Mingo’s family having an ‘M’ name.

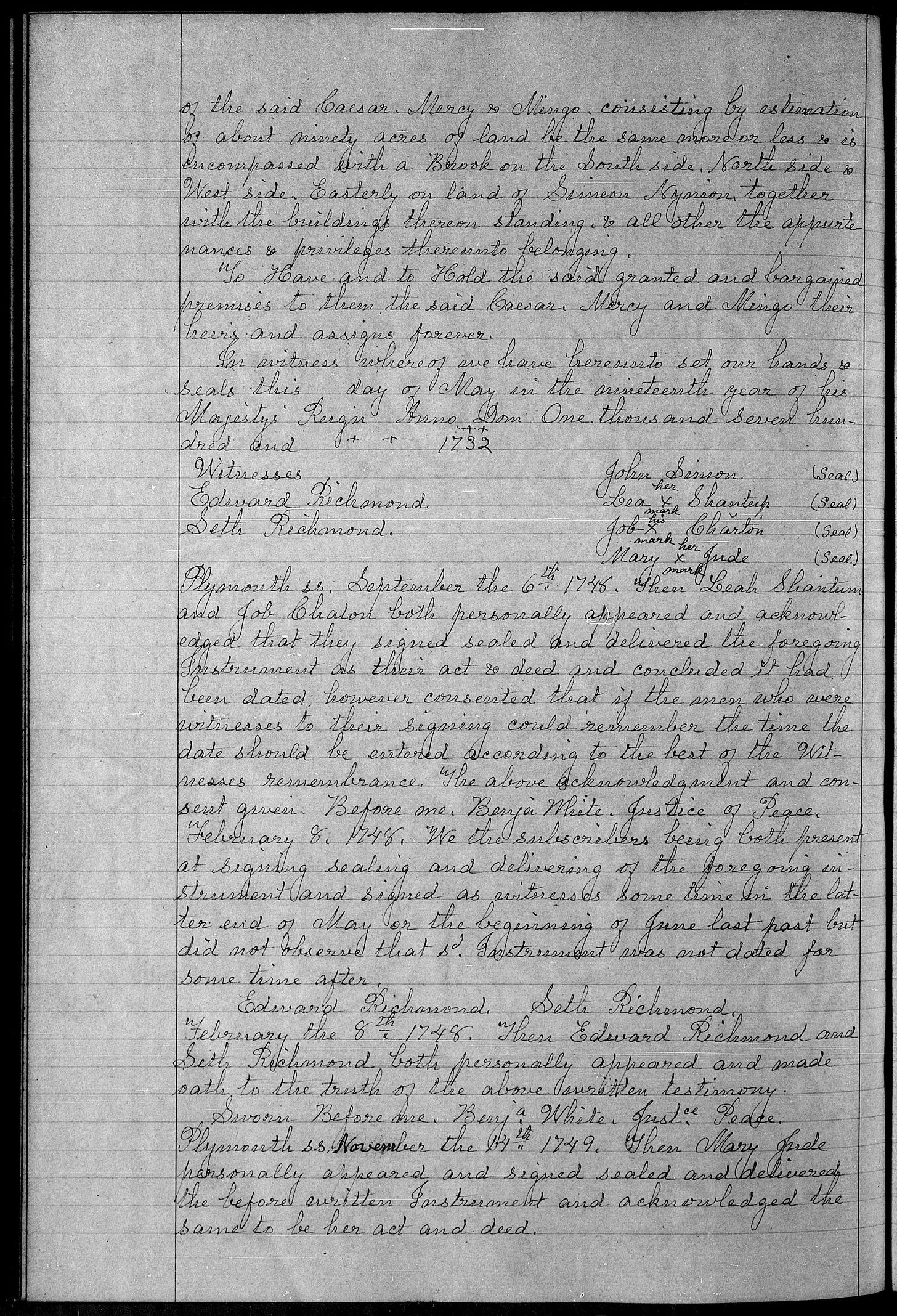

Of course, Mr. Gundaway having the first name of Richard and an “M”-named daughter is a tepid connection; but staying in Plymouth County Deeds, we encounter Richard, Mingo, and Mercy “Gonduary” referenced in a 1732 transaction (quoted in a 1752 deed) at the Titicut reservation of Middleborough. Mercy married a free Black man named Caesar Easton, whose ancestors were manumitted by a Newport Quaker family of the same last name. Examining the set of facts, it feels safe to speculate (stress speculate) that Dick and Mingoe from 1704, Dick and Mingo from the 1708 batisms, Richard and Mercy Gunderway from 1712, and the trio attested to in the 1732 transaction are all the same family.

The story of the descendants of Richard and Mingo Gunderway could fill a Ph.D. dissertation. In fact, many of the leads used to build this entry came from George R. Price’s The Easton Family Of Southeast Massachusetts: The Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations Of Human Rights Activism, 1753-1935, a 2006 dissertation housed at the University of Montana. It has subsequently been revised and published as a book in 2020. Here are some selected examples of how this extended family fared after Dick and Mingoe’s 1704 manumission.

Caesar and Mercy fought to maintain their land rights. Elkanah Leonard, Esq, a wealthy and litigious Middleborough landholder, sued Ceasar Easton in 1755 to eject the Eastons from 17 acres allegedly seized in 1753. Leonard was awarded £10 plus the court costs for his attorney, the James Otis, Jr, “County of Suffolk, gentleman.”

In 1763, Caesar petitioned the legislature to stop further encroachment on his land by Leonard and Stephen David, an indigenous man who acquired land between Easton and Leonard through the marriage to two Titicut women.

Digital Archive of Massachusetts Anti-Slavery and Anti-Segregation Petitions, Massachusetts Archives, Boston MA, 2015, "Massachusetts Archives Collection. v.105-Petitions, 1643-1775. SC1/series 45X, Petition of Josiah Edson", https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KSHXIL, Harvard Dataverse, V4 Next, through Price summarizing William Cooper Nell, we learn that Caesar and Mercy’s son James Easton. . .

. . .educated himself, became a skilled blacksmith, served the patriot cause in the American Revolution, successfully operated his own iron foundry for over twenty years, and ran one of the earliest combined vocational and academic type schools in the U.S. He also led what appears to have been the earliest sit-in protests in U.S. history, protesting against segregated seating in two Massachusetts churches, first in 1789 and several more times during the next 37 years. Easton accomplished most of this while residing in North Bridgewater, Massachusetts (now Brockton, about twenty miles south of Boston), a town in which free people of color, in the early 19th century, made up only about one and one half percent of the population, and the extended Easton family made up nearly half of that “free colored” population.

James’s son Hosea Easton was a firebrand abolitionist minister in Hartford, Connecticut, who advocated for reparations, arguing:

I repeat, that emancipation embraces the idea that the emancipated must be placed back where slavery found them, and restore to them all that slavery has taken away from them. Merely to cease beating the colored people, and leave them in their gore, and call it emancipation is nonsense. Nothing short of an entire reversal of the slave system in theory and practice—in general and in particular—will ever accomplish the work of redeeming the colored people of this country from their present condition.

James’ grandson and great-granddaughter were Benjamin Roberts and Sarah Roberts. Benjamin was a well-known printer in Boston’s flourishing African American activist community and filed the 1848 Sarah Roberts v. City of Boston school desegregation suit. Although Roberts lost in court, he kept working, and in 1855 the Massachusetts legislature passed a school desegregation law. Later, the Roberts case was exploited in the odious Plessy v. Fergeson to prop up the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Other descendants include:

Revolutionary War veteran Richard Gunderway of Pembroke.

Richard’s son, locally-notable North River gundalow operator Jeremiah Gunderway, of Pembroke and South Scituate/Norwell.

54th Massachusetts Infantry soldiers from South Scituate/Norwell, brothers William and Warren Freeman.

An impressive family to be sure. Also, It’s important that the military service of Black and multiracial men in these eras are not undervalued as forms of civil rights activism. There was strong political opposition to allowing soldiers of color in the Revolution, peacetime, and the Civil War. Not only did these men serve, but it took tireless advocacy to break down barriers to service, and these men and their surviving families faced discriminatory practices when self-advocating for benefits that they earned, all of which is a continuous spectrum of activism.

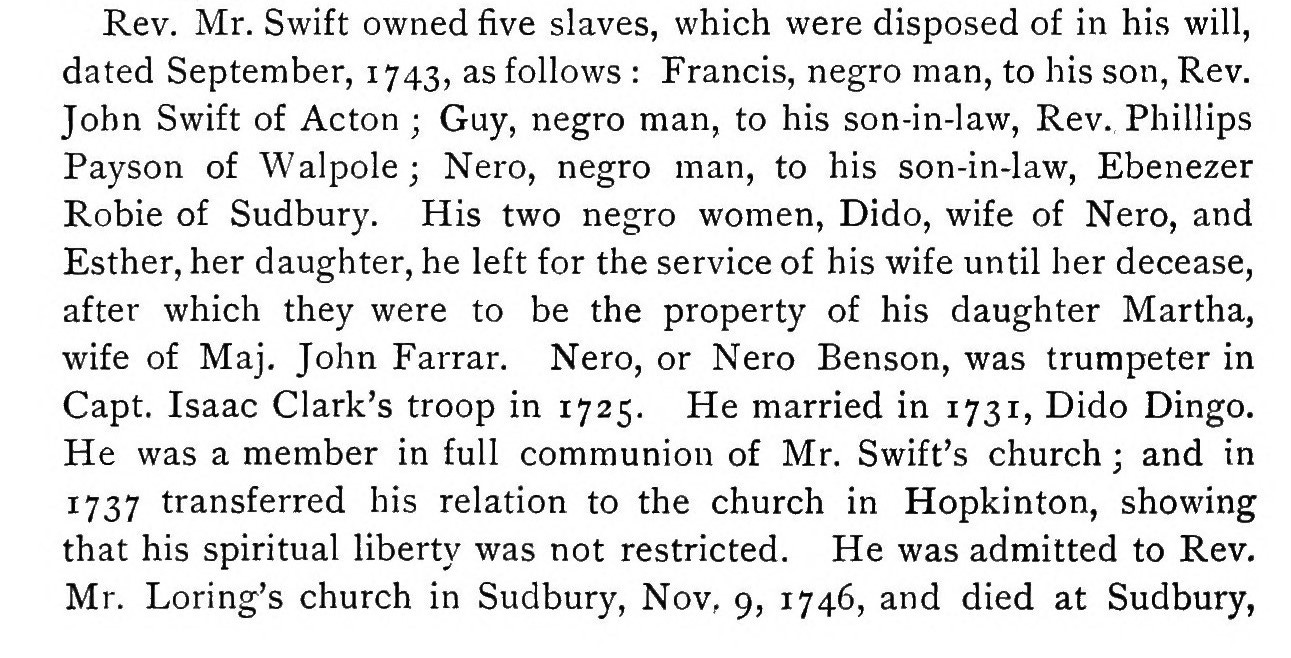

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. John Swift

Framingham’s first minister, the Rev. John Swift, held at least five people in Slavery. This ancient “History of Framingham” details what happened to the enslaved individuals in Swift’s household.

Two other enslaving ministers appear in Swift’s probate file. Rev. Swift gave a man Francis his son John Swift, minister of Acton, Massachusetts, and son-in-law Philip Payson, minister of Walpole, inherited Guy. The men responsible for propagating the gospel were also resposnsible for propagating slavery through the Massachusetts countryside.

Goodbye Horses—Equine Atlantic: New England’s Horse Trade to the West Indies in the 18th Century

My media recommendation this week comes from the Connecticut Historical Society and Dr. Charlotte Carrington-Farmer. This presentation is superb and deserves more than 77 views. (Three of those views are from me.)

Dr. Eric Kimball tells us that 75% of horses exported from British North America to the West Indies came from Connecticut.

From the late seventeenth century through to the end of the eighteenth century, countless New England vessels braved the eighteenth-century Atlantic in a quest for profit by delivering horses to the sugar colonies in the West Indies. In this virtual talk, Dr. Carrington-Farmer will explore why New England emerged as a breeding ground for horses, and how it came to dominate the equine trade to the sugar colonies. New England’s horse breeding and trading success were tied to the wider currents of rival empire building through the markets for sugar and slaves.

Essential Links

Read about another son of Caesar and Mercy Easton in Augusta’s Forgotten Minister: John Eason (1786-1879), Mary Blauss Edwards

Playwright, journalist, and activist Wiliam Edgar Easton, Wikipedia..

December 15, 2022, Jews, Slavery & the Meaning of Freedom, a virtual program presented by Dr. Paul Finkelman for the Touro Synagogue National Historic Site.

The Gunderway surname appears under numerous variations in the records. If you plan on researching the family further, consider the following spellings: Gundaway, Gundeway, Gundway, Gonduary (in the Tituct deed), and Gunway (Pembroke, MA, and Mercy’s R.I. marriage record).