Investigating a 1724 "interracial" marriage in (West) Bridgewater

The mystery of Sash and Margaret Linsford's marriage in Plymouth County. Also: Abington's Moses Sash/Nash.

Last week: Notes on pivotal Massachusetts women to kick off Women’s History Month; if you missed it, check it out! This week: I close out a mystery that has eluded me for over a year. Next week: one remarkable Revolutionary muster roll for Evacuation Day. - Wayne

Was Margaret Linsford white?

The Margaret Linsford mystery has vexed me for more than a year.

Colonial Massachusetts record keepers were diligent in noting when someone was not white. Furthermore, it was unusual for African-descended people to be noted with a first and last name and not be classified as “negro,” or “mulatto.” So what to make of Margaret Linsford marrying “Sash, negro,” in (West) Bridgewater, Massachusetts,1 in 1724? The textual evidence indicates that Linsford was white.

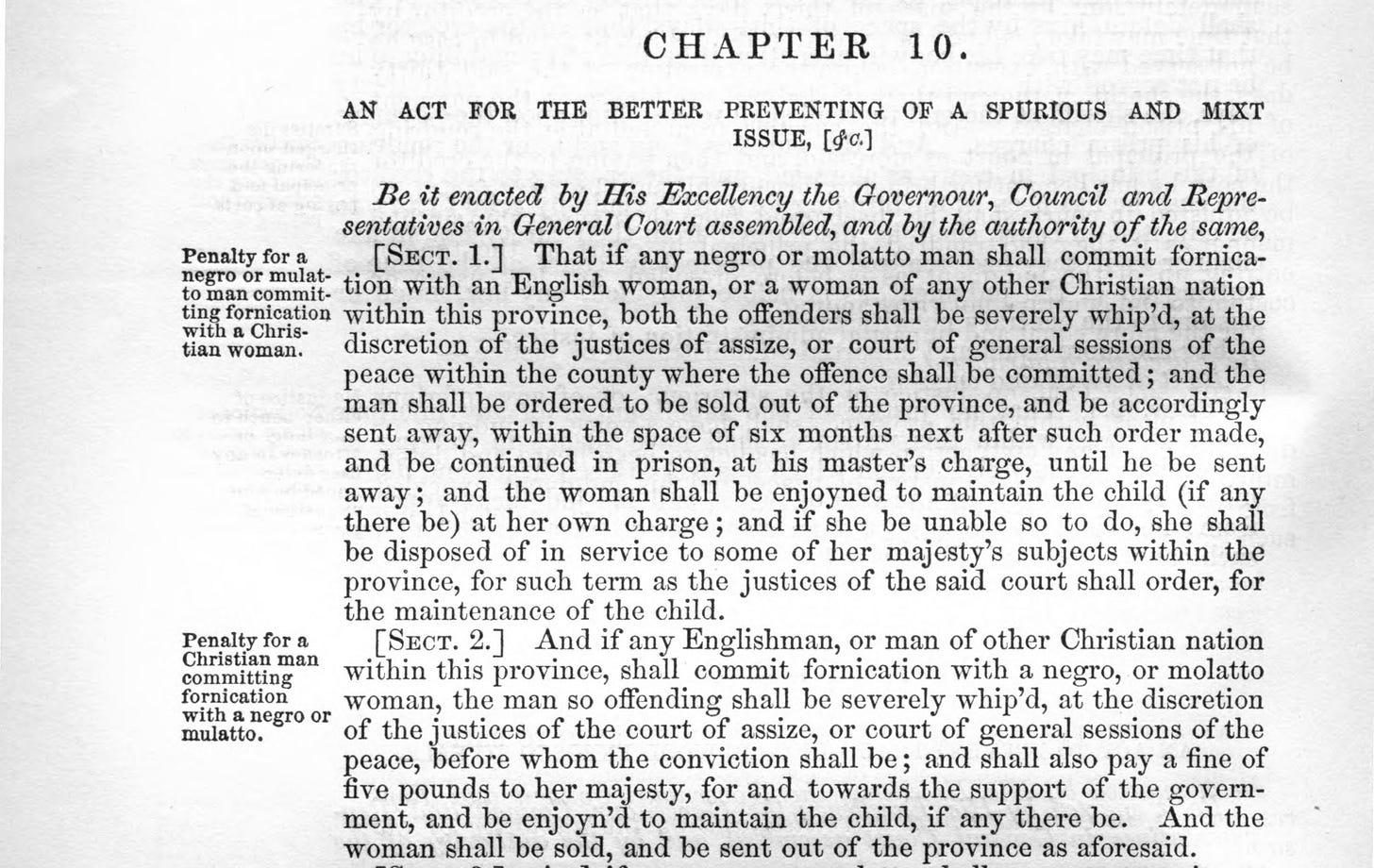

Although interracial marriage was not explicitly prohibited, “An Act for the Better Preventing of a Spurious and Mixt Issue” passed by the General Court in 1705 made it clear that it was dangerous to carry out a love affair across racial lines. For example, the law stated that “if any negro or molatto man shall commit fornication with an English woman. . .both offenders shall be severely whip’d. . .and the man shall be ordered out of the province.”

If Linsford and Sash took a risk and this was a sanctioned interracial marriage, it would be a significant data point in the history of race and slavery in Plymouth County and worthy of scrutiny.

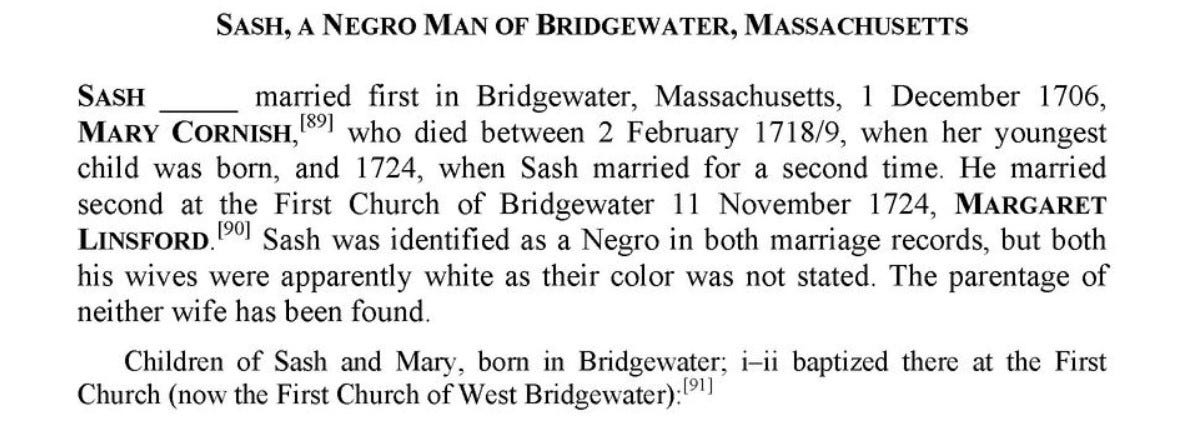

Little has been written about the Linsford-Sash marriage, and when Margaret’s race was discussed, speculation always concurred with my speculation. At the end of the day, though, it’s still speculation. I often hit a dead end trying to unravel Margaret Linsford’s identity, and I could not find a creative search query to unlock informative results. But recently I stumbled upon a three-part treatment of the family of Sampson Dunbar in 2012 -2015 editions of The New England Historical and Genealogical Register. (See first image above.)

The Sash and Dunbar families are tenuously connected via Dunbar’s second marriage, yet the author thought it fit to include a short appendix on the mononymic Sash. Here, he too concludes that Margaret Linsford and his first wife Mary Cornish were “apparently white.” Well, who am I to argue with The Register? Still, it didn’t sit right. And this information is potentially ten years outdated.

Although I’ve cracked many a mystery via the Eleven Names Project, this one wasn’t in the cards. Google and the regular genealogical databases weren’t going to cut it. Fortunately for me, someone already knew and published the definitive answer on Margaret Linsford’s racial identity, even if she was unaware that many diligent people questioned it.

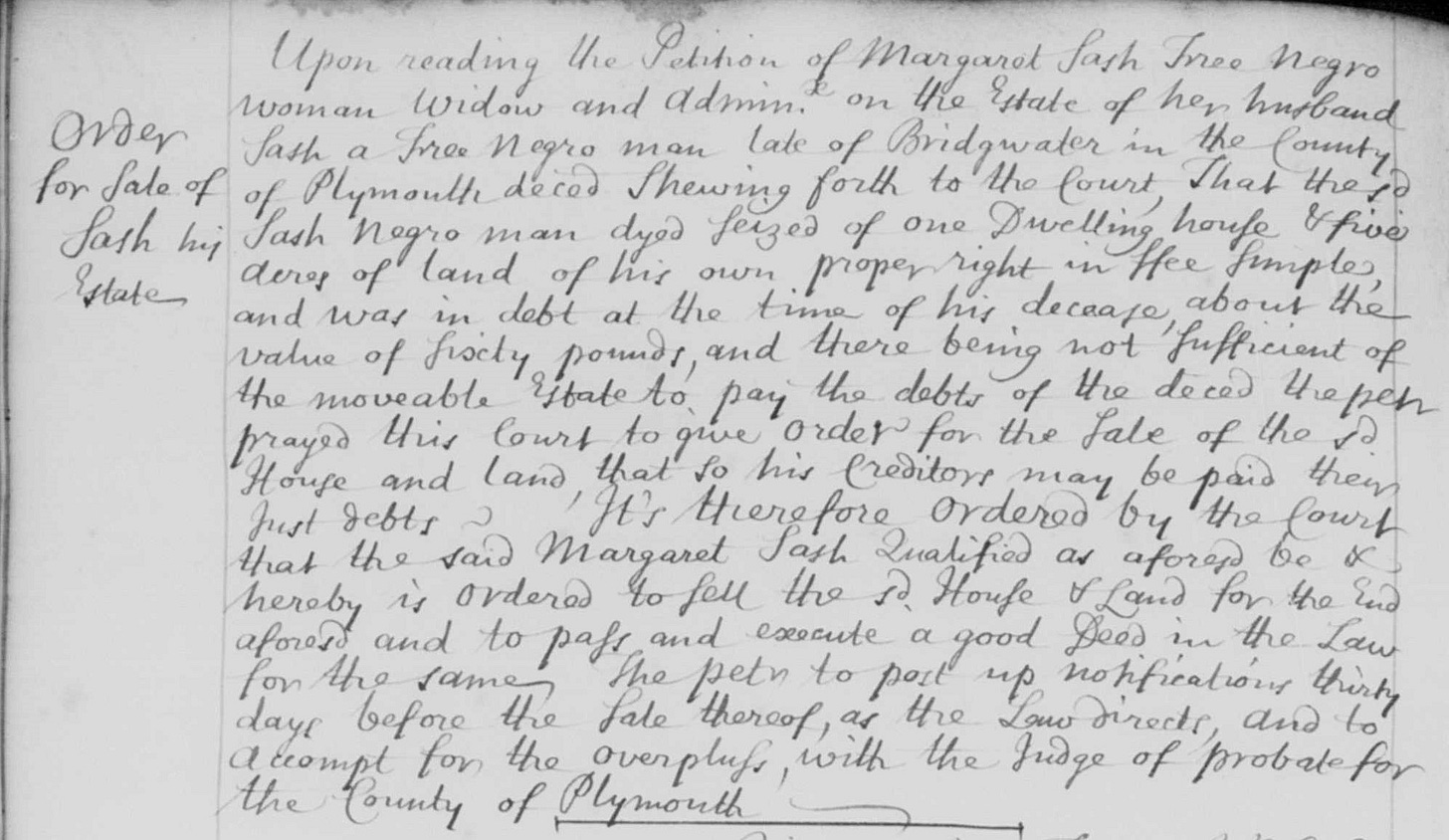

Dr. Gloria McCahon Whiting discusses Sash and Linsford in a chapter in her 2016 Ph.D. dissertation2 that was subsequently adapted into an illuminating journal article.3 Whiting quotes a court case that refers to Margaret Sash—as it was common for a mononymic man's name to become his family's surname—as a “Free Negro Woman.” So using Whiting’s footnotes, I quickly located the case transcript and, with mercifully legible penmanship, we see that Margaret Linsford Sash was a “Free Negro Woman.” Additionally, in Sash’s 1730 probate file, Margaret is listed as “Margaret Sash Negro Woman.” Case closed.4

Moses Sash, Moses Nash, & Old Moses of Abington, Massachusetts

It seems to me that there were at least two different Black men named Moses who lived in colonial Abington, and genealogists and historians (myself included) tend to fuse them into one person.5

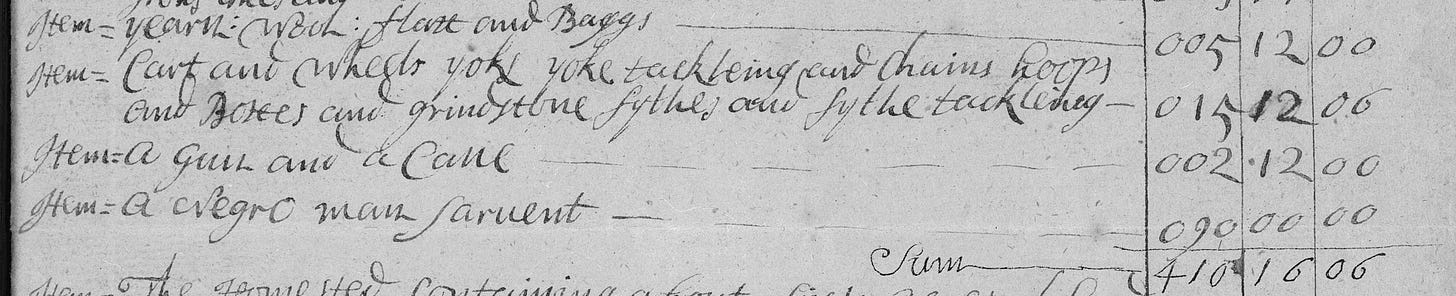

The confusion arises because the name “Moses Sash” appears in Abington’s records a few times, and he was reputed to have business dealings with the Nash family. Furthermore, when James Nash and his family moved to Abington in 1710, they brought Moses, an enslaved child. Nonstandard colonial spellings and the name changes of African-descended people being what they were, it’s not invalid to hypothesize that some Abington record keepers erroneously recorded Moses Nash as Sash. But the Nash family was prolific in Abington, so it’s not as if the Nash surname was exotic or rare.

Abington bordered the northern parish of Bridgewater (Brockton, once called North Bridgewater), and both Bridgewater and Abington sources note a Moses and his sister Margaret6 lived in North Bridgewater; this indicates that the child Moses who was enslaved by the Nash family and the free Black Moses Sash were not the same people.

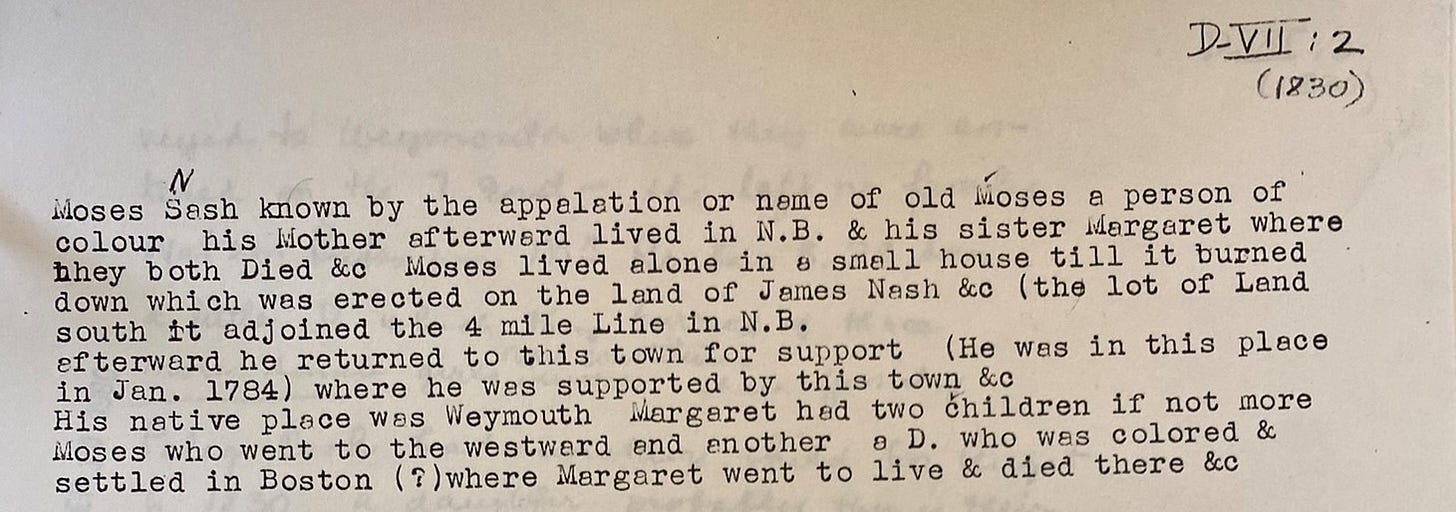

But there are more wrinkles. Abington historian Cyrus Nash writing in 1830, notes that Moses Sash lived on James Nash’s property on the Abington/North Bridgewater line in 1784. Here, he conflates the biographical details of the two men. Sash had a sister Margaret in Bridgewater, the same town he was born in. Nash was the Moses who was from Weymouth.

Moses Sash Sr. and his sister Margaret were the children of Sash an Margaret Linsford who we met above. This Moses died c. 1758. In 1759, Moses Sash Jr. and his sister Hulda were left in the guardianship of Thomas Penniman of Stoughton. Junior grew up to be a soldier who served in the Revolution, enlisting in Western Massachusetts7 where Daniel Shays later recruited him to be a captain to his "regulators" during the famous Shays’ Rebellion of 1786 and 1787. Moses and Shays were close, as Shays was said to seek Sash's counsel. After the charges against Shays' men were famously dropped, Moses Sash Jr. lived in several Western Massachusetts communities and settled with his wife in Hartford.89 If Moses Sash Jr. ever lived in Abington, it was before the Revolution.

So perhaps there are three Bridgewater-area Moses Sashes and one Moses “Nash,” although we don’t know if the enslaved Moses identified himself as a Nash.

Further, we have this mention of a Moses where in 1783 Christopher Dyer disclaims that he “forbid[s] all Persons trusting or entertaining a negro Man, named Moses, now living in Bridgewater, on my Account, for I will not pay any Debt of his contracting after the Date hereof.” Again, the detail about Bridgewater makes me think that this is Moses Sash, not Nash.

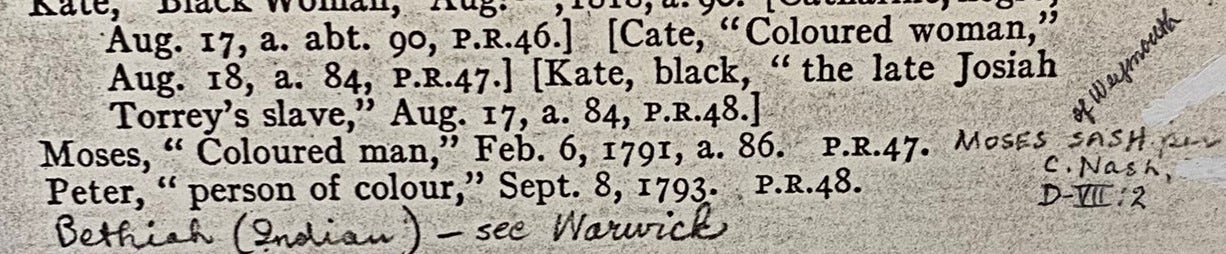

Abington Vital Records record Moses, a' “Coloured man,” dying on February 6, 1791, at age 86. The so-called Cyrus Nash House Book, held in Abington’s Dyer Memorial Library & Archives collection, notes that “Old Moses” died in a house on Adams Street, no year given. Therefore, the Moses who died at age 86 in 1791 was probably the once-enslaved Moses “Nash.” This calculates to a birth date of 1705 and comports with James Nash arriving in Abington with a “boy” named Moses in 1710. Sash of Bridgewater’s first child was born in 1712, and his first male child, James, was born in 1717.

As best as I can tell, three descendants of Sash and Margaret Linsford named Moses were born in Bridgewater before the Revolution. However, the lives of Abington's Moses Sash and Moses “Nash” were obscured due to geographic and orthographic proximity, and they were fused into the singular “Old Moses.”10

West Bridgewater did not set off from the mother town until 1820. Still, the West Bridgewater Vital Records book is composed of records from the western parish church, which is in today’s WB.

Whiting, Gloria McCahon. (2016). "Endearing Ties": Black Family Life in Early New England.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. online: Harvard University.

Whiting, Gloria McCahon. “Power, Patriarchy, and Provision: African Families Negotiate Gender and Slavery in New England.” The Journal of American History 103, no. 3 (2016): 583–605. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48560224.

As for Sash’s first wife, Mary Cornish, I strongly suspect she was not white—perhaps Indian—as the Bridgewater town records I consulted did not list anyone’s race, including men with names like “Cuffy” and “Cato” who were obviously Black or mixed race.

There’s precedent for this in Abington. A Black man named Cuffy died in 1775 and is conflated by Cyrus Nash and later historians with Cuffy Rosaria Sr., who’s recorded in Revolutionary Muster rolls for years afterward.

Perhaps Margaret (Sash) Sewall, sister to Moses Sash Sr. Moses Sr. died in 1758.

Note that Cyrus Nash says that Margaret Sash had a child named Moses who moved westward. This is another conflation, as the westward-bound Moses was the son of Moses Sash Sr. and Sarah Colley.

For a biographical treatment of Moses Sash Jr., see Carvalho, Joseph. 2011. Black Families in Hampden County, Massachusetts, 1650-1865. p. 209.

See also: Moses Sash: Black Worthingtonian of Shays’ Rebellion by the Worthington (Mass.) Historical Society.

I reserve the right to be wrong. Perhaps Moses Sash Jr. lived in Abington between Stoughton and the Revolution. shoulder.shrug.emoji. Posit your theory in the comments below.