Welcome, readers. This is a reminder to new subscribers that there are 30 back editions of Open Notebook and a call to explore the archive. Take a look! -Wayne

Last year, I won a grant to identify and compile records of slavery in Massachusetts through the Northeast Slavery Records Index. The database is “an online searchable compilation of records identifying individual enslaved persons and enslavers.” Most valuable are the NESRI locality reports. Users can investigate records of slavery on a town, county, or state level. [Click here to see the locality report for Cambridge, Massachusetts.]

Publically launched in 2018 as the New York Slavery Records Index, the project expanded to New Jersey and the six New England states. John Jay College of Criminal Justice (CUNY) administers the index, and state-level partners of NESRI include the estimable Maine-based Atlantic Black Box Project and Connecticut’s Witness Stones Project spearheaded by career history teacher Dennis Culliton.

Witness Stones Project

Throughout his professional life, Mr. Culliton collected information on slavery in Connecticut but became frustrated at the lack of public engagement with the historical record. A friend of Culliton remarked how Germans wrestle with the historical memory of the Holocaust through Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones.” The original Stolpersteine are four-inch cubes of concrete mounted with a brass plaque commemorating those murdered by Nazis. The stones are nestled in the paving stones and cobbles adjacent to the homes and businesses of the people memorialized. Culliton and his friend wondered if the same could work to honor the enslaved in Connecticut.

The Witness Stones Project is not exclusively a historical marker/memorial program; placing the stone is the last step. For a community to qualify for a stone, a school or civic group must complete educational programing and compile research on the individual to be memorialized. So along with a visible stone, the primary and secondary research on that person is cataloged, and the names on the stone have fleshed-out biographies to accompany them. Furthermore, students and teachers gain tools to expand historical research into their community’s Black history.

And yes, the Witness Stones Project’s adapted Stolpersteine concept works in Connecticut. In partnership with more than a dozen communities, the project has placed 130 stones in Connecticut, and stones in New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. WSP also partnered with Historic Deerfield to place the first 19 stones in Massachusetts.

Culliton notes that the rapidly-expanding Witness Stones Project will be pretty busy placing 40 more stones within the next few months.

Further reading: Game Changer: Witness Stones Project by Dennis Culliton (April 2023). From Connecticut by the Numbers.

Slavery and Universities, Colleges and Schools

Longtime readers of the Eleven Names Twitter feed know that I’ve been framing Harvard as a hub-and-spoke delivery system that spent decades blasting slavery into the New England hinterlands. You may be familiar with my #ordainedslavery Twitter thread where I tweeted 104 examples of Massachusetts and New England ministers who were enslavers; if you consult the classic nineteenth-century histories of Massachusetts towns, you’ll notice that many parishes’ “first ministers” were enslavers.

There are strengths to the landmark Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery. First, the report recounts enslavement on campus and documents how colonial faculty and benefactors were deeply entwined with slavery. Later, the report chronicles Harvard folks who enriched themselves through the business of slavery in the nineteenth century.

But one opportunity to expand this excellent work is to investigate Harvard’s impact in propagating slavery throughout the countryside as its graduates and influence spread across the region. It seems the folks leading NESRI arrived at a similar but further-reaching conclusion.

When campus officials model and normalize slavery, this is an important educational message to students, who as alumni bring these values and norms back to their home communities. Thus, slavery at the campus can promote slavery in distant communities. This is particularly true when the campuses are educating future ministers and religious leaders, who then model and espouse slavery to their congregations and home communities.

Validation at last!

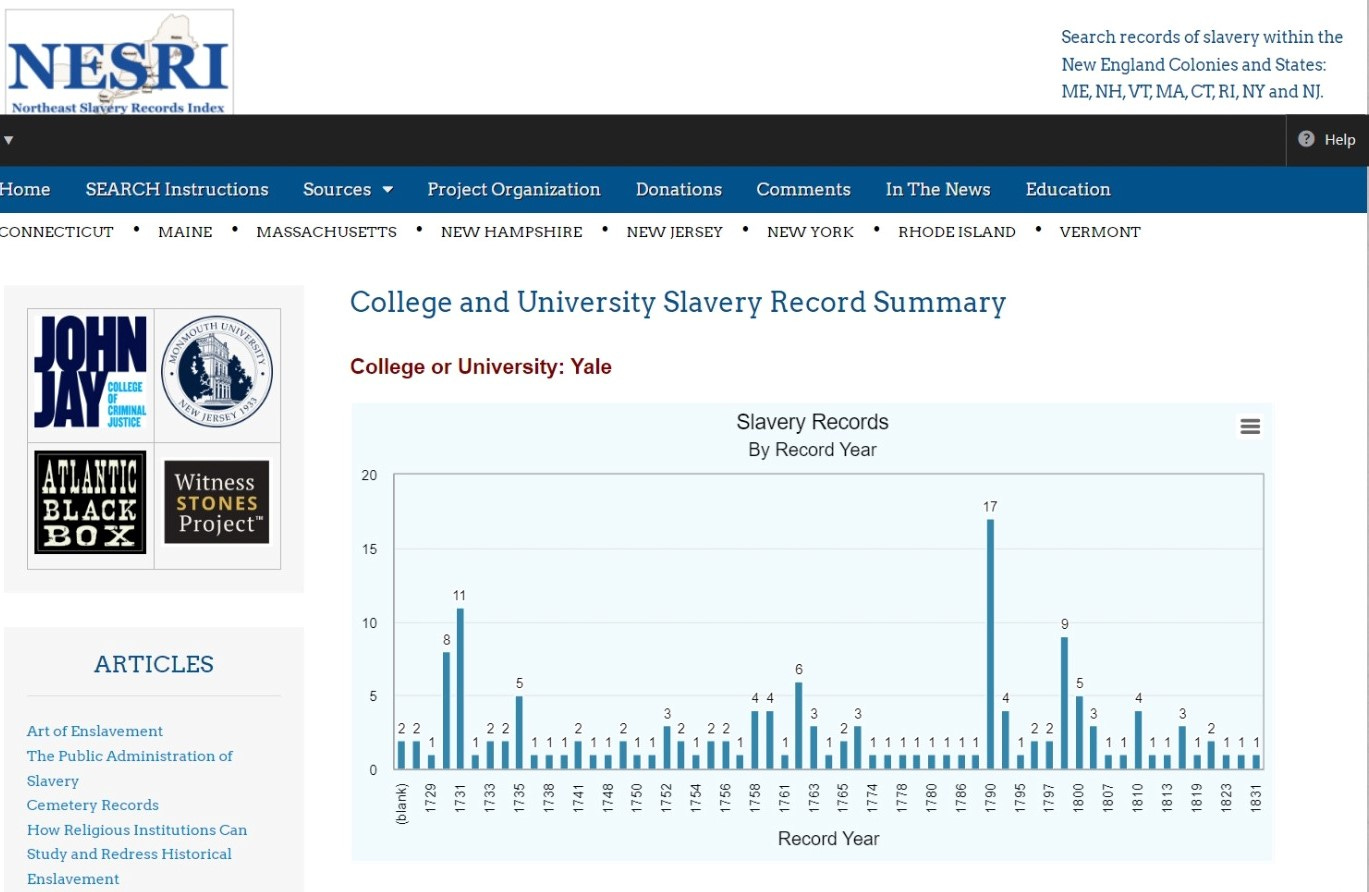

The blockquote above comes from NESRI’s introduction to its Slavery and Universities, Colleges and Schools project. The college project is a work in progress, and NESRI will continually add records, but this first phase gives a nice idea of how it will be useful in the future. Indexed institutions are Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Brown, Rutgers, Dartmouth, and Union College.

Where are the records of slavery in the Massachusetts suburbs?

I’ve provided NESRI with 4,000 records of slavery in Eastern Massachusetts from 16411 - 1783. The first phase of my project combed the counties east2 of Worcester County besides Suffolk. I’m working on Suffolk County for phase two and seeking to add 3,000—3,500 records. I used several types of sources, but the cornerstone of my data are the New England Historic Genealogical Society’s “Vital Records to 1850” volumes (nicknamed the “tan books”) which are now public domain and widely digitized. For example, look at the number of records on this page of Andover marriages alone.

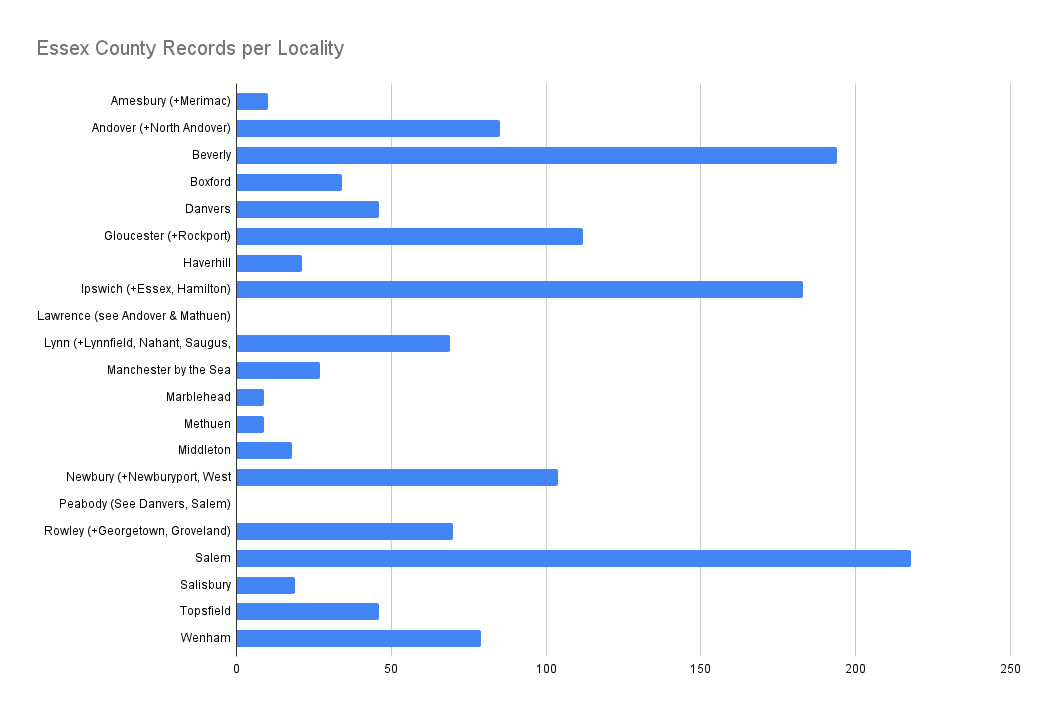

Identifying the records is half the battle. The NESRI coding team is working diligently to convert my submissions into usable data. In the meantime, I’ve adapted my tracking spreadsheets for the Open Notebook audience. I was not surprised that Essex County had the most records, but I was surprised when I found that Plymouth County ranked second.

CLICK HERE to access the full “Eastern Massachusetts Vital Records of Enslavement at a Glance” Google Sheet. I encourage you to look up your current or ancestral hometown.

This data reflects vital records that are widely available and digitized and does not indicate unindexed and unpublished (and offline) archival records. However, I think it’s fair to hypothesize that communities with a high number of indexed digitized records contain untapped caches of archival materials relating to slavery in town clerks’ archives, local libraries, and historical societies. And I hope this information nudges people to start digging in their own backyards.

The earliest Massachusetts vital record for enslaved people (of which I am aware) dates to March 19, 1641, in Boston. "Hope son of Mingo. a neger born 19th day 3rd month." Further down the page is the birth record of "Waite-still" Winthrop. This is John Winthrop’s son, a Salem Witch Trials judge, diarist, and slaveholder.

The original version of this edition (and the one that appears in subscribers’ emails) erroneously said “west of Worcester County.”

This is incredible work - thank you so much for your diligence.