Mariah Negro vs. Cornelius Briggs (pt. 3)

What happened to Molly, and Grace, and Tony Sisco?

Over this series' first and second editions, we’ve learned that Mariah is the earliest African person we can name in Plymouth Colony. Her life was well documented, and in 1716, Mariah—by then a free woman—and her husband Tony Sisco brought suit against Cornelius Briggs Jr. to free the Siscos’ eight-year-old daughter Molly, whom Briggs was detaining and enslaving in neighboring Pembroke.

The case and its appeals dragged on until 1720, and Briggs enslaved Molly the entire time. Sadly, Mariah did not survive to see victory, but Molly recovered her freedom and a small amount of cash covering court costs.

Molly’s Fate

The burning question, though, is what happened to Molly after her landmark freedom suit? The short answer is that we don’t know.

Mariah had three children; her son Will Tomas was sold in 1703 to Hingham’s Jabez Wilder, and below we will examine the compelling story of Molly’s younger sister Grace Sisco. But turning to Molly herself, she disappears from the record.

Or does she? In a 2012 edition of the New England Genealogical and Historical Register, there was a suggestion that Mary Crouch, a woman from Scituate, might be Molly alias Mary Sisco. In 1750, Mary Crouch's daughter, Patience Crouch (baptized in 1732), married Samson Dunbar,1 a Black man from Braintree.

It’s an interesting theory, but it seems like a stretch. Molly would have been aged 24 in 1732, a prime age for motherhood; unexplainable, though, is the Crouch surname. No one surnamed Crouch appears in eighteenth-century Plymouth County records other than Mary and Patience. Furthermore, we know that Mary Crouch was a “single woman” because 1731 court records show she was fined “four pounds” for fornication. Notably, the race of Mary and Patience Crouch is not noted in the baptismal record, the court case, or in Patience’s 1750 marriage intention.

Mary Crouch is a mystery. For Molly to be Mary Crouch, it would’ve been contingent upon several things. However, the only thing we can know about Crouch is that she was a single mother who lived in Scituate in 1731-1732 and lived in a county where no one else shared her surname. Although I suspect Mary Crouch is not Molly Sisco, I hope I am proven wrong because Mary Crouch is an ancestor to Sarah Roberts, the African American girl who, through her father’s efforts, filed the landmark Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston school desegregation case in 1849. It would be fantastic to connect Mariah and Molly’s lineage to another famous activist parent/daughter pair; for now, though, it’s wishful thinking.

Grace Sisco escapes an indenture (but likely enters another)

Scituate vital records show that “Grace, negro” was born to “Meriah” on March 20, 1713. No father is listed, and Mariah didn’t marry Tony until 1714. This is likely the birth record of Grace Sisco who appears in a 1741 indenture contract2 with Deacon Joseph Clap(p) Jr.3 Fornication was illegal in colonial Massachusetts and the courts enforced penalties; yet, the indenture contract underscored to Grace that her sexuality would be policed and over-scrutinized as she must agree not to “commit fornication or contract matrimony” over the seven-year term.

Joseph Clapp Jr. was no stranger to holding Black neighbors in bondage. His wife Hannah Briggs was born in the Walter Briggs house where Mariah once lived, and she was the granddaughter of Capt. Cornelius Briggs.4 Clapp lived adjacent to his slaveholding father Joseph Clap Sr. on lands known today as Norwell’s Cuffee’s Lane and the Cuffee Hill Conservation Areas. The year before Grace's indenture, the Rev. Nathaniel Eells records that “Cuff negro man of Mr. Joseph Clap + Flora negro of Mr. Thomas Clap were married Jan. 22 1740/41.” According to Joseph Sr.’s will,5 Cuffee was still enslaved in 1747, but at some point, Cuff and Flora adopted the last name Grandison/Granderson and had four or five children.6 After their sons Charles and Simeon returned from the Revolutionary War, the brothers settled on and owned portions of the contemporary conservation lands that bear their father's name.

Grace’s indenture was the subject of a lawsuit the following year. In 1742 Joseph Clap Jr. sued fellow Scituate man Samuel Stockbridge alleging that Stockbridge “enticed away and took into his own service one Grace Sisco a negro woman who was at that time and is now a covenant servant of the plaintiff.” Surprisingly, the jury found Stockbridge not guilty and ordered Clap to pay his court costs.

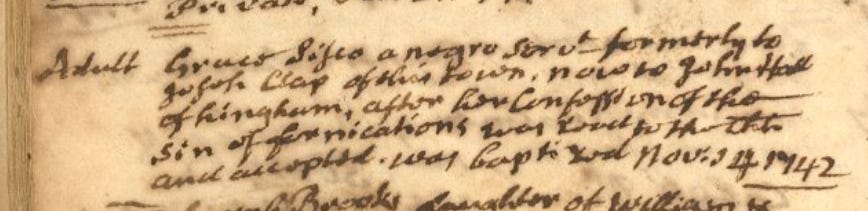

In November of 1742, Grace, now age 29, was baptized by her father’s enslaver and her sister’s advocate, the Rev. Nathaniel Eells, but only before Eells read her confession of fornication before the congregation. The tell-tale sign of fornication is pregnancy, but sadly there is no record of Grace Sisco giving birth. Eells further notes that Grace was “servt. formerly to Joseph Clap of this town now to John Hall of Hingham.” Seven years later, Prime Coley and Grace “Thiscoe” (presumably a mistranscription from the original record) marry in Hingham in 1749. This is the last record I have for Grace. Primus Cooley, who died in 1777, married a woman named Rachel in near-by Weymouth in 1775.7

Tony, Phebie, Ruth, and other Siscos

The Rev. Nathaniel Eells played an outsized role in the Siscos’ lives. He was Tony’s enslaver and he married Mariah and Tony in 1714. He was Molly’s advocate in court and baptized Molly’s younger sister Grace as an adult two decades later.

Mariah died circa 1718 before Molly recovered her freedom, and in 1719 Eells married Tony to his second wife, Phebie. In 1724, Eells baptized Tony and Phebie as adults along with their young daughter, Ruth; the family was now enslaved by Thomas Rogers8 of Marshfield, the grandson of Frances (Rogers) Briggs, who first inherited Mariah from her second husband Walter in 1676.9 Mariah’s family could not seem ever to be rid the Briggs family.

Other Siscos

The Sisco surname proliferated throughout eighteenth-century New England. We find the name in Norton, several Franklin County communities, and the name (spelled ‘Cisco’) rates an entry in Joseph Carvalho III’s superlative Researching Black Families in Hampden County, 1650-1865.10 I don’t know how or if any of these Siscos further afield relate to Anthony Sisco of Scituate and Marshfield, but he is the earliest man in Massachusetts with that surname. Perhaps moving west may have been the family's only escape from Scituate servitude.

Conclusion

(Coming next Open Notebook.)

Patience Crouch’s baptismal record is found here. Her marriage record is found here. Vital Records of Scituate, Massachusetts, to the year 1850. NEHGS.

Spchronometry.WordPress.com. 2019. Two Indian Indentured Servant Documents, Massachusetts. I found Grace Sisco’s (uncited) indenture by Google searching “Grace Sisco” + Scituate. Shout out to the anonymous author of the (perhaps) abandoned blog, spchronometry.

For disambiguation of Scituate men named Joseph Clap(p), see The Clapp Memorial (1881), pp 113 & 127.

See: L. V. Briggs (1938), History and genealogy of the Briggs family, 1254-1937, Vol. 1. p. 241.

Will of Joseph Clap (Sr.). 1747. Plymouth County Probate Records. Probates v. 11-11B 1748-1750, 1841-1848.

See pp 434-435 of Vital Records of Scituate, Massachusetts: to the year 1850. NEHGS.

Primus Cooley’s marriage record can be found in Vital Records of Weymouth, Massachusetts, to the year 1850. NEHGS. See also: Suffolk County Probate File #16423.

The 1746 will of Thomas Rogers notes a “negro girl named Phebie.” It's unclear if the Phebie in Rogers' will is the baptized Phebe, Phebe and Tony's daughter, or another person altogether.

I learned of this familial link through Pattie Hainer’s unpublished work.