Mariah Negro vs. Cornelius Briggs (Pt. 2)

Mariah is the first African resident of Plymouth Colony that we can identify by name, and she also initiated a landmark suit to free her daughter.

In writing this edition of Open Notebook, I owe a debt to Edward L. Bell.1 Mr. Bell is the author of the book Persistence of Memories of Slavery and Emancipation in Historical Andover (Shawsheen Press, 2021) and the eye-opening Atlantic Black Box article, Freeing Eral Lonnon: a Mashpee Indian Presumed a Fugitive Slave in Louisiana, and the Role of Native People in the History of Judicial Abolition in Massachusetts.

I lean heavily on Edward’s legwork and expertise and thank him for permission to use his work. - Wayne

Mariah Negro vs. Cornelius Briggs (Pt. 1)

Mariah Negro is a neglected yet foundational figure in Massachusetts history. Purchased in Boston as a child in 1673 by Scituate shipbuilder Walter Briggs, Mariah later sued for the freedom of her daughter Molly (née Mary), who had been wrongfully imprisoned and enslaved by Cornelius Briggs.

The series' first installment examines Mariah’s well-documented life from 1673 - 1716. This second installment reviews seven court records involving Mariah and the wrongful detention and enslavement of her daughter Molly alias Mary.2

Tony and Mariah Negroes vs. Cornelius Briggs

I root Mariah’s “founding mother” status in two facts. First, although African slavery took hold in Plymouth Colony twenty-to-thirty years before Mariah’s 1673 arrival in Scituate, she is the third identifiable African-descended person and the first enslaved Plymouth Colony resident that we can name.3

The second cornerstone of Mariah’s foundational status is the freedom suit she and her husband Tony Sisco initiated to liberate their daughter Molly. In the previous newsletter, I established that Mariah was a free woman at the time of Molly’s 1708 birth. Curiously, though, Briggs asserted that Mariah was not a free woman and it was unclear why; fortunately, Briggs’ losing argument survives in court records. Although both parents are plaintiffs in this lawsuit, it’s ultimately Mariah’s freedom status—not Tony’s status as an enslaved man, and not Mariah’s marriage to Tony—that is the central factor in this case. This gives Mariah central importance in this case and in history.

Moreover, this suit brings into stark relief that even “free” Black folks were second-class citizens. Beyond the pittance awarded in court costs to the Siscos and their prochain ami, the Rev. Nathaniel Eells, it’s striking to the modern eye that there is no criminal penalty for kidnapping and detaining a child while pressing her into slavery.

February 1716

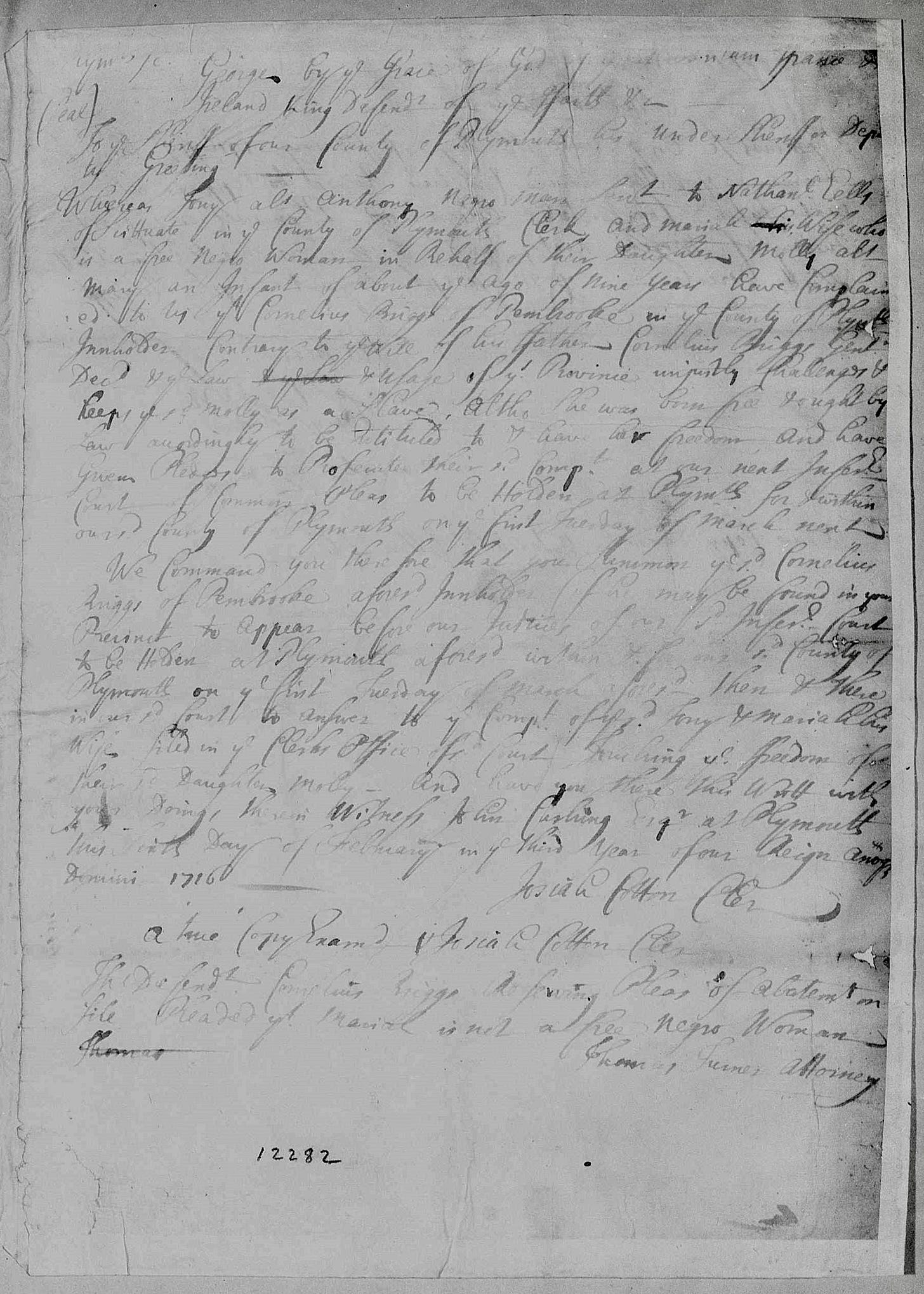

In the Suffolk Files Collection, File #12282, we find six pages regarding the Siscos and Walter Briggs. The first document found is a writ issued by the inferior court at Plymouth in 1716. Here the Siscos allege:

Whereas Tony alias Anthony, a negro man servant to Nathaniel Eells of Scituate. . . and, Mariah his wife who is a free negro woman, in behalf of their daughter Molly alias Mary an infant of about the age of nine years have complained [to the court that] Cornelius Briggs of Pembroke. . .inholder, contrary to the will of his father. . . and of the law and usage of the province unjustly challenges and keeps the said Molly as a slave, although she was born free taught by law.

The court ordered Cornelius Briggs to appear at the inferior court held at Plymouth in March, but the paper trail doesn't pick up until April of 1717.

April 1717

Tony & Mariah Negroes vs. Cornelius Briggs } In an action to prove the liberty4 of the plaintiffs' daughter Molly alias Mary, detained by the said Briggs as a slave contrary to the law and [his father’s] will.

Here, Briggs pleaded for an abatement because he claimed, without evidence noted in this case file, that Mariah was “not a free negro woman.” The court wasn’t buying it—

“We find for the plaintiffs the freedom of their daughter Molly. Sued for court costs. . .£5:10.” So Tony, Mariah, and Molly won the initial suit in 1717. Briggs naturally appealed. And frustratingly, Briggs continued to hold Molly in captivity.

April 1718

Returning to Suffolk File #12282, we find a brief in which Briggs outlines his rationale for why Mariah was not free. On the first page, Briggs’ made procedural arguments, first about the damages and court costs paid to the Rev. Eells, the point of which I don’t fully understand. Next, he complains (as he did in the first hearing) that he wasn’t served a summons with the proper notice.

But the meat of the complaint comes when Briggs argues that Mariah couldn't be free. It begins:

“Whereas there is but three ways of being made a freeman: either by birthright or by naturalization [or by] denization; but neither Tony nor Mariah have either of them, and all that are not freeman must be [considered] aliens, of which there are two sorts:” “alien friends” and “alien enemies.” “Alien,” of course, meant non-English people.

The “alien enemy” distinction is important; the 1641 Massachusetts Body of Liberties allowed the enslavement of “lawful Captives taken in just wars, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves or are sold to us.” This broad clause was the pretense used by New Englanders to instigate the Pequot Massacre in 1636 and ramp up the enslavement and slave trade of local Indians. It was also the eventual justification for purchasing and enslaving Africans.

Therefore, I infer that the argument Briggs’ lawyer is making is this: Mariah was justifiably enslaved under Massachusetts law either because she was sold to an English person as a slave or she was born of a woman who was enslaved; as Briggs notes, the freedom status of the child follows that of the mother. Furthermore, because common law didn’t permit Capt. Cornelius Briggs the power to manumit Mariah via his last will and she wasn’t naturalized or denized, Mariah was never legally freed and was still the property of Capt. Briggs’ estate. Hence, it would be impossible for Molly to be born free, and she was the property of Capt. Briggs’ heirs.

The brief further argues that because Africans were aliens, they had no standing to sue white Christian men in Massachusetts. To paraphrase the argument, why should negroes have access to the courts when they don’t pay taxes, they can’t inherit, they can’t bargain if they trespass (default on debt), can’t be sued in civil court because their masters are responsible for their liabilities, and they can’t serve on juries, etc.?

This argument did not succeed; if it did, the history of gradual abolition in Massachusetts, the core of which was freedom suits driven by the enslaved, would likely be unrecognizable to modern historians. Yet, Briggs’ argument wasn’t rejected right away.

May 1718 appeal

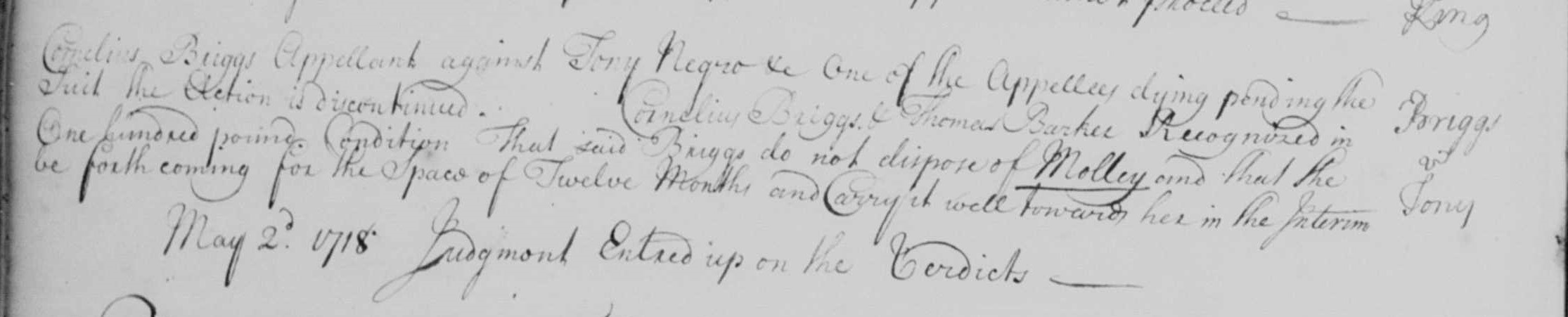

The above appeal was discontinued because one of the appellees died.

There is no death record for Mariah, and we confirm her death only through this court record; her scarce appearances in vital records are in the Scituate births of her daughters Molly and Grace. However, even in these records, she is listed as the anonymous “Meriah,” and other documents are required to corroborate the life of Mariah Sisco.

Born before 1673 and died circa 1718, Mariah likely passed away between the ages of 48 - 55. Her oldest child, Will Tomas, was approaching thirty, Molly was about ten, and Grace was four going on five.

Although this case is discontinued, the court thankfully ordered Briggs not to “dispose of Molly” in the forthcoming twelve months giving the plaintiffs time to mount another suit.

July 1719

The following year, Molly and the Rev. Eells re-file the plea for freedom. Tony is notably not a party to this suit. One wonders if he accompanied his daughter to the hearing. Had Tony already moved to the home of Marshfield’s Thomas Rogers?5 Was he not allowed the “day off” for the court appearance?

Molly alias Mary Negro, by her next friend Mr. Nathaniel Eells vs. Cornelius Briggs} Touching the freedom of said Molly. . .held by the said Briggs as a slave. . .

In sum, Molly recovers her freedom again, and Briggs appeals again; Briggs retains Molly. A more legible copy is filed in the Suffolk Files #14033. Also in this file is a previously-issued writ commanding Briggs to appear at this hearing.

April 1720

Molly, now twelve, permanently wins her suit that spanned four years. The court found that Briggs failed to prosecute his appeal and that Molly “recovered her freedom and costs.” But, again, it’s jarring that there was no compensation for Molly’s time, labor, or damages, or that Briggs paid no criminal penalty.

I’m neither a lawyer nor a legal scholar, but I hope this and the previous edition establish that Mariah and her family are worth greater scrutiny, contextualization, and analysis. Additionally, the next Open Notebook will probe what happened to Molly and Grace and examine the proliferation of the Sisco family into the nineteenth century.

Edward L. Bell, (2022) Research Summaries of Massachusetts Freedom Suits 1660–1784 (last revised March 8, 2023.) pp. 48 - 52. online: https://www.academia.edu/76814209. Bell has fluency with this material and his entries for these cases are more concise. I believe my multimedia approach and Bell’s mastery of the subject are complementary, and I recommend Bell’s work for richer understanding and context.

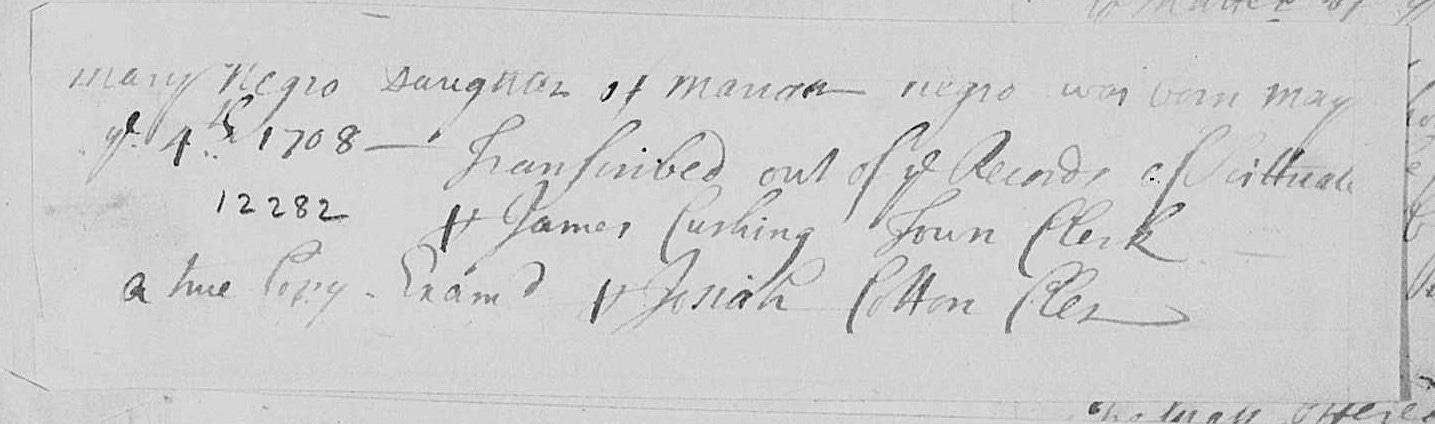

In the previous newsletter, I mentioned that Mariah’s daughter was referred to Molly and Mary interchangeably. You will see her referred to as “Molly alias Mary” in several of the above court documents. Furthermore, I previously excerpted the vital records of Scituate to show Molly’s birth to “Meriah” as May 4, 1708. Below is a note from the Scituate town clerk held in the Suffolk File #12282 that corroborates the almost-anonymous vital record extract.

In 1643, a “blackamore” is listed as living at Plymouth Colony. In 1653, a “neager maide servant” of John Barnes accused John Smith of receiving stolen goods. In 1673, we find Mariah. Next, in 1676, during King Philip’s War, we find Jethro, enslaved by Thomas Willett, who passed along crucial intelligence and is credited for saving Taunton.

A copy of this is found in Suffolk File # 12282. Bell notes that while the Plymouth County file denotes this case as a case to “prove the liberty” of Molly, the Suffolk File copy lists uses the Latin plea de libertate probanda.

As we’ll see in the following newsletter, the Rev. Eells married Tony and Febe in November of 1719, and they are both listed as servants to Thomas Rogers of Marshfield. It’s unclear when this move happened, if Tony was sold, or if this was some indenture to which Tony had a degree of choice.

READ PART 3 HERE:

https://elevennames.substack.com/p/mariah3