The Sylvester Family, Slavery, and Early Civil Rights Activism in Norwell, Mass.

Issue # 15: Activism and pushing for full citizenship is a Sylvester tradition, especially amongst Sylvester women.

Hello & welcome new readers. First, I want to thank Wendy Bawabe and the Norwell Historical Society for publishing this essay in its February newsletter. Also, in case you missed it, check out PYRATICALLY AND FELONIOUSLY: The Taking of Joachim/Cuffee. Thank you for subscribing and sharing. - Wayne

Deep New England Roots

What does it mean to have multi-generational roots in our New England hometowns? White English people weren’t the only people here before the Declaration of Independence. Wampanoag, Mattakesett, and other native peoples used and cared for Norwell’s land and waters for millennia and are still here. In 1765, when Fruitful Sylvester was born enslaved, the population of people of color in Scituate/Norwell was 5%, significantly higher than the colony’s average. That year, census takers categorized 14 Scituate/Norwell residents as Indian and 107 residents as “negro.”

What’s important to understand is that this enslaved and free Black population were not transients who existed alone without kin and community. Although some mid-eighteenth-century enslaved South Shore residents were born in Africa, by the mid-1700s, most Black or multiracial residents of Massachusetts were native to the colony and lived close to where they were born.

Still, crafting narratives of enslaved families in colonial Massachusetts remains challenging. Slaveholders forced family separations and frequently stripped enslaved people of their last names. Despite this, we can and must build family trees. We see undeniable evidence of foundational Black families like the Sylvesters, Freemans, Gunderways, and others deeply embedded in and contributing to Plymouth County for decades before the Boston Tea Party. These Black families then sent children to the Revolution, to labor on shipyards, toil as housewrights and maids, establish a tight-knit free Black community, and send great-grandsons to the Civil War at a higher rate than white Norwelleans, and they are our neighbors in twenty-first-century Plymouth County—deep local roots indeed.

Family Tree

Attentive Norwell history enthusiasts may remember Fruitful from my story about his abolitionist sister, Venus Manning, or Briggs’ Shipbuilding on North River:

One of the characters of the time was Fruitful Sylvester. He was a negro born of a slave in the service of a Mr. Sylvester who lived on the Chittenden place during the Revolution. He died about fifty years ago and will be remembered only by the older people. He worked for the Fosters in 1820, and to show what wages were at that time he was paid for ‘Killing, cutting up and salting a cow, 62 cents. ‘For shearing six sheep, 36 cents.’ ‘Cutting two cords of hard wood at Grey’s Hill, $1.00,’ and other labor equally cheap. He was known the country round.1

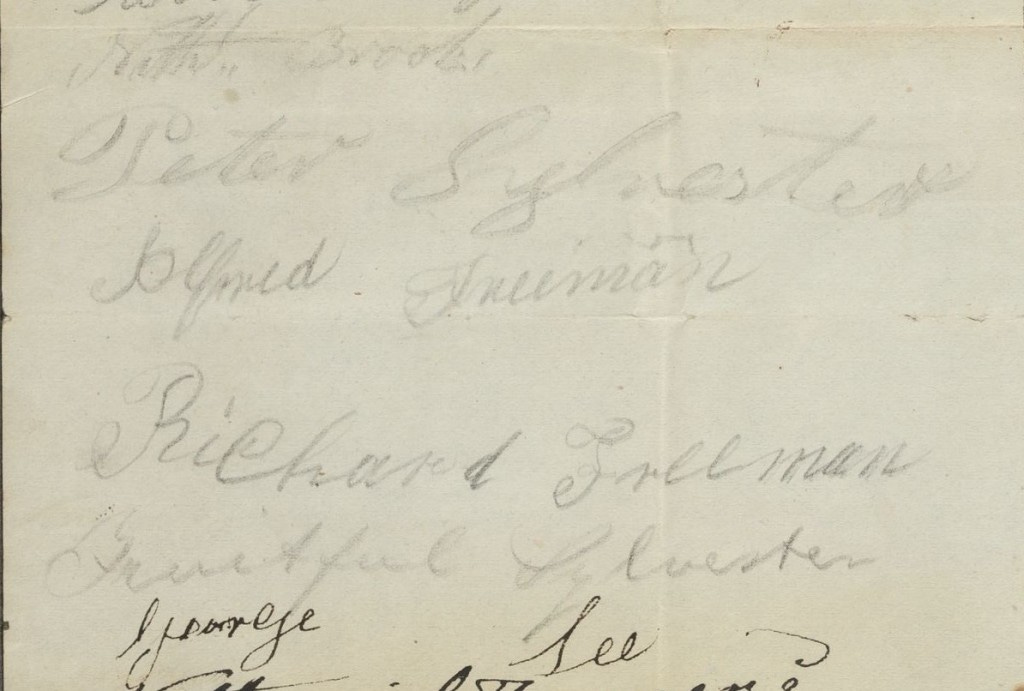

But who were Fruitful Sylvester’s parents? Luckily, we have strong circumstantial evidence to build a speculative family tree. First, note that Fruitful’s oldest sister was named Catherine. Then, digging into family genealogy, we find that Fruitful’s first daughter was named after his wife Patty, but the couple named their second daughter Catherine; was Fruitful’s daughter, also called ‘Katie,’ named after her aunt? Or perhaps it was her grandmother?

Fruitful and his siblings were born enslaved to “Mr. Sylvester,” a shipbuilder. In Hanover church records, Newport and Kate, “negro slaves belonging to Nath’l Sylvester,” married in 1760; Fruitful’s oldest sister Catherine was born two years later in 1762. During this time, deeds show that shipbuilder Nathaniel Sylvester owned land in Hanover and Scituate.

Further compelling, in 1745, we find in Norwell church records that an enslaved woman named Cuba baptized three children: Richard, Thomas, and Katherine. Katherine’s age is unclear, and given that Cuba gained admission to the church a few months previous in 1744, Katherine may have been anywhere from toddler-age to nine(-ish) years old. And if Cuba baptized Katherine as young as age 3, she would have been 18 at the 1760 Hanover marriage of Newport and Kate and aged 20 at the 1762 birth of Catherine Sylvester.

Another enticing clue is that Cuba married a Hanover man named Jupiter, who died in 1747. Later, we find Cuba moving to Hanover in 1768, where she was admitted to the Hanover Congregational church with a recommendation from the “2d Church of Scituate” (today’s First Parish UU in Norwell.) It appears Cuba was sold or given away, and perhaps she moved closer to her daughter and grandchildren. And I can’t help but wonder if Venus (Sylvester) Manning’s celestial first name was a nod to her grandfather Jupiter. If correct, this lineage establishes three generations of Sylvesters in the Norwell/Hanover area before the Revolution.

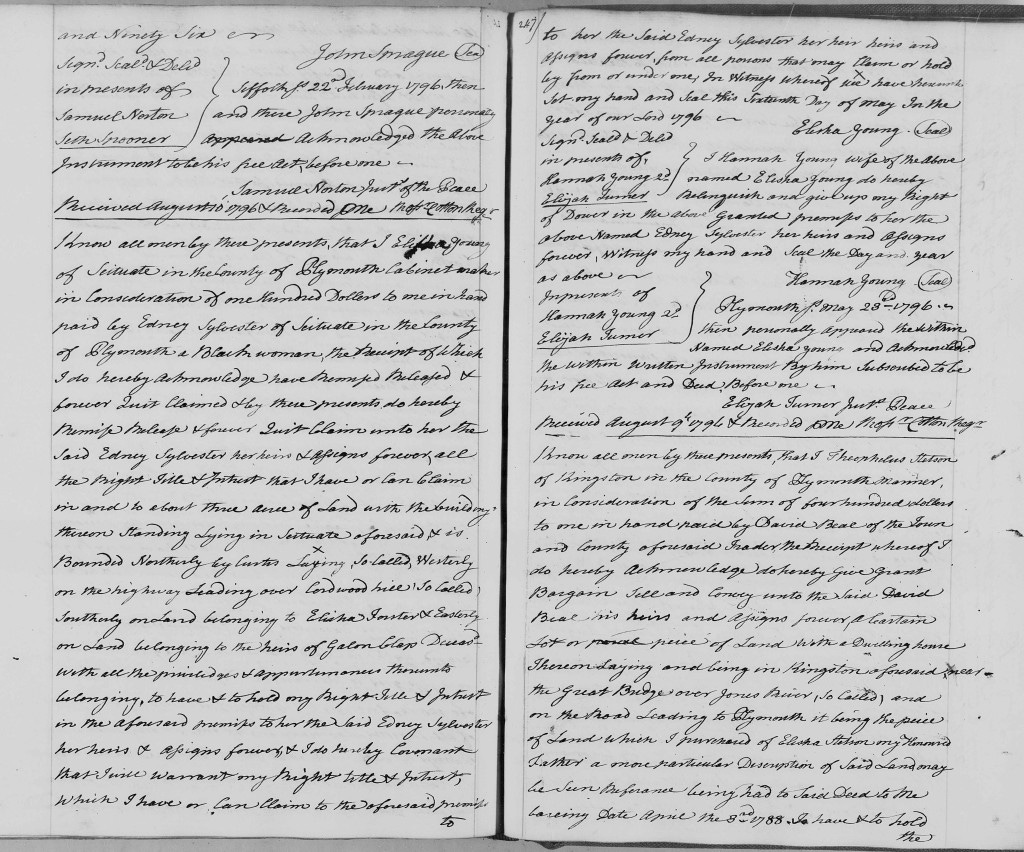

Land Transactions

1783 was an important year; it closed out the Revolution, and it’s cited as the year gradual emancipation gained momentum in the Commonwealth. Ten years later, Fruitful and Edna Sylvester, one of Fruitful and Venus’s four sisters, bought property in South Scituate, which today is Norwell.

A Plymouth County deed records a three-acre purchase from Melzar Stodder near Grey’s/Cordwood Hill. Fruitful sold most of that property in 1795. Then, in 1796, Edna, noted as “a Black woman,” appears by herself on a deed recording a land purchase, seemingly repurchasing the property.

Edna and Fruitful executed their 1793 purchase the year after the 1792 Parting Ways land grant to Black Revolutionary soldiers in Plymouth. The earliest black land ownership in Scituate attested to in town deeds references a man named Frank/Francis “Negro” in 1699. His 1714 probate file bequeaths to his wife Margaret an unspecified acreage of property worth £100. And we know, through the excellent work of Pattie Hainer, that the Grandison family gained land in the 1740s at Norwell’s Cuffee Hill.

Nonetheless, the Sylvester purchase of 1793 is amongst the earliest Black land purchases in Plymouth County, and antique maps attest that Venus Manning and the Sylvester family owned three dwellings on Circuit Street. Their heirs remained there in the early 1900s—it’s worth noting that this continuous Black land ownership touches three centuries.

Activism, Citizenship, & Legacy

Activism and pushing for full citizenship is a Sylvester tradition, especially amongst Sylvester women. When Cuba joined the church and decided to baptize her three children, although enslaved, she exercised a choice that pushed for marginal integration into white society, a choice she presumed would benefit her children. Further, Fruitful and Edna’s enslaved parents couldn’t buy and own property, and there were numerous barriers to Black property ownership in eighteenth-century Massachusetts. Yet, the Sylvesters found ways to assert property rights and reap financial gains.

What’s more, Venus Manning became a life member of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. She left a gift promoting abolition that was the equivalent of five to six months wages for a working person. And Fruitful exercised his conscience, too—in 1839, the year of his death, his signature appeared on a petition that opposed Florida’s admission to the Union as a slave state.

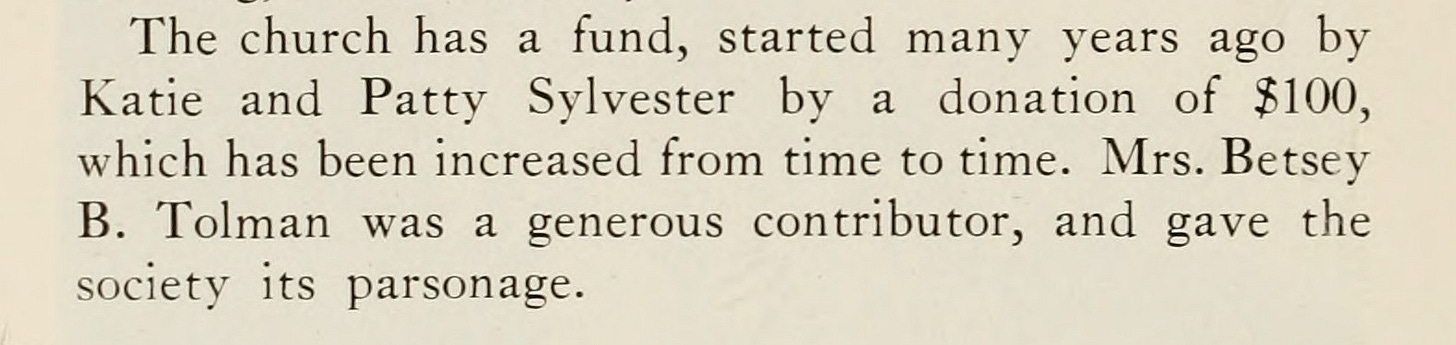

Furthermore, Fruitful’s daughters Patty and Katie were founding members of Norwell’s Church Hill United Methodist Church; constructed in 1852, it still anchors Church Street today. There are many reasons to organize a church, but it’s evident that Black women Patty and Katy felt some void in South Scituate’s spiritual community and exercised their spiritual agency in the tradition of their aunt Venus and great-grandmother Cuba.

Another physical mark the Sylvesters imprinted on Norwell’s landscape is the impressive row of six conspicuous family headstones at Norwell’s First ParishCemetery. Again, the Sylvesters made a statement; these are the earliest Black headstones in this burying ground that interred African-descended folks for more than a century previously. Moreover, the Sylvesters aren’t scattered to disparate corners of the cemetery; the family rests eternally together. This plot is a marker of financial success and is Norwell’s de facto monument to the enslaved and free Black community of South Scituate/Norwell that stretched from the 1670s to the Civil War. These long-overlooked stones are rare, regionally essential treasures that we must preserve.