Hello, Open Notebook readers! Can we leverage modern resources to update local nineteenth-century histories of slavery?

New England abounds with antiquarian town histories chronicling the region’s early days. These endeavors were popular from the 1830s to the early twentieth century when a local well-to-do white man would self-publish a comprehensive but monotonous narrative volume. Examples of such tomes include Drake's The Town of Roxbury (1878), Roads' History and Traditions of Marblehead (1880), and Dwelley and Simmons' History of the Town of Hanover (1910). Some of these works, like Old Scituate (1921), were published by organizations like the DAR and authored by a committee of women and men. However, today’s subject, Mary de Witt Freeland’s The Records of Oxford, Mass.1 (1895), stands out as a rare volume written solely by a woman.

Of course, these volumes are problematic: they lack citations, include oral histories that range from accurate accounts to folklore, and even the most progressive white authors displayed anti-Black bigotry that permeated their writings. Furthermore, some authors were outright racists.

Distinguishing between fact and fiction can be daunting. Still, we live in an era where digitization and indexing of historical records have become a research superpower. Moreover, these texts are in the public domain and are ripe for reexamination.

Reprinted below are pages 596 - 600, which discuss Oxford in the time of slavery and its aftermath. I am struck by the treatments of Phylis Whittemore and Dinah—women who statistically should be lost to history, yet we can tenderly interpret their memory through Freeland’s historical sketch.

The text is lightly edited for readability and annotated with primary sources and my observations. - Wayne

Annotated excerpt from “The Records of Oxford Mass. . .” (1895)

Dinah, "A Slave."

In the town papers appears the draft of a petition to the General Court, from the Selectmen, representing that "Dinah a Negro Woman is in the Town of Oxford without any means of support by which reason she has become chargeable to said Town she being Aged and infirm; by the best information we can get she was born in Sudbury. . .& came into this Town upwards of 30 years ago & at length became a servant of one Charles Dabney who came into this Town from Providence in the latter part of ye year [1776]2 (or a little later) but did not in any wise gain a habitance in said Oxford, & remained servant to said Dabney until ye adoption of this State Constitution soon after which time said Dabney her master removed back to said Providence & there soon after deceased & left said Negro in Oxford without any means of support by which reason she has become chargeable to said Town. Therefore your Petitioners pray your Honours to take the case into your consideration & (give) us relief by considering her one of this State's Paupers, etc." An endorsement on this paper is dated 1807.

Dinah, as appears, was for many years after Dabney's removal a faithful domestic in the family of Josiah Wolcott.

Boston and Dinah, two slaves, with their two children, Genny and Silvy,3 were in the family of Josiah Wolcott, Esq., of Oxford. They were at one time in the possession of Duncan Campbell, Esq.,4 his brother-in-law, and when Dinah was no longer a slave she had a home in the family of Major Archibald Campbell, and previously in the family of Samuel Campbell. Faithful Dinah!5 ever in the kitchen, with her dark skirt and neat calico short dress (in the fashion of the time called a "long short"), with her blue checked apron and neat turban. In figure Dinah was extremely short but immensely stout. Sometimes she would be seen standing in the chimney corner making chocolate,67 for she was always busily at work, or maybe giving her orders to her young masters Campbell in the absence of their parents,8 and at whatever happened in the family or neighborhood she would at once declare “I've tellt ye so.” Notwithstanding her temper was not always the sweetest, there was in Dinah a kind heart.

During her service in the Wolcott family she was much attached to her two young mistresses. Miss Wolcott and her sister, Miss Mahetabel. After their marriages, for they left Oxford for distant homes in New Hampshire and Maine, Dinah would make many inquiries for the young ladies, and if opportunity offered, many messages of her love and "duty" were sent to them.9

The following town record is found of Dinah, after a long life of faithful service: “The town paid Samuel Campbell for supporting Diner a negro wench up to the 2 day of November 1807."10— Oxford Town Records.

Nothing now remains to remind one of Dinah but her picture embroidered by the Wolcott ladies representing her as making the tea by pouring water from a tiny tea-kettle into the china cups containing the tea, as she was standing behind the chair of her mistress at the tea table. Jack, another slave in the Wolcott family, is represented in embroidery as passing to guests a silver salver with glasses filled with wine.11

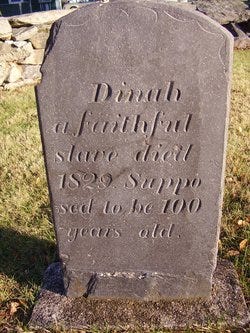

Dinah lived to be one hundred years of age1213 and died in 1829. Her grave was in the northeast corner of the churchyard, styled the poor corner. The late Andrew Sigourney, Esq., who had married one of the ladles of the Wolcott family, placed a headstone to her memory, naming her faithfulness in servitude. The humble gravestone of Dinah records the death of the last slave in Oxford.

Story of Phylis Whittemore

After the termination of slavery in Massachusetts near the close of the last century, Jack and Phylis Whittemore, two freed slaves, with their child, Deborah,14 came to Oxford. They were most respectable in their characters. Their home was a small brown cottage on the old Charlton road, one mile west of the old North Common, just west of the river. It was long known as Jack's house. Jack died of a lingering consumption. “January 1 1797 gave Abner Mellen amount of one dollar and thirty-three cents for digging Jack Whittemore’s grave." "On January 30, 1796, the State paid the town a bill for the support of Jack Whittemore." — Town Records.

In 1760, or at a still later date, a vessel was at anchor off the Guinea coast; her boats were lowered and when manned put out for the shore. Phylis and her two brothers younger than herself were gathering nuts and berries when captured by the sailors. They were soon dragged on board the vessel, then came the battering down below hatches, and there like rats in a cage young and old were down in the hold of the vessel.

If before being placed on board a slave-ship any poor African attempted to escape he was struck on the head and when senseless was thrown on board. Whenever the hatches were opened the poor captives would draw themselves off to the far end of the hold, as all who were sick were drawn out and thrown overboard with the dead.

Phylis and her brothers were brought to Boston and were purchased from a slave-ship. Phylis was ten or twelve years of age according to her own account and with an uncovered head, with a single scant garment of coarse hempen cloth covering her body, with her two brothers stood friendless, dejected and travelworn on the auction slave-stand in Boston, Mass., her sad face showing a hopeless sorrow, while the auctioneer glibly enumerated her various qualities — good looking, healthy, active — with all the coarseness and indifference that he would have spoken of an animal or any article of commerce.15 Soon Phylis and her brothers were sold, and all to different masters, never to meet again. During her whole life Phylis would speak of this parting scene with bitterness and with maledictions.

Phylis Whittemore was much employed in service in the family of Mr. James Butler, and Deborah, her child, was in service to the family for many years of her life, having been taken by Mrs. Butler in her childhood on the death of her mother. She was taught reading, spelling, and to keep accounts correctly, with plain needlework. Deborah excelled in all departments of the kitchen and as a housekeeper. At her death she was mourned as a loss to her friends for her moral excellence of character.

November 24, 1800, Phylis Whittemore left Mrs. Butler's for home in a snow storm, and was found dead in the road next morning.

Among a list of notes and papers delivered to Peter Butler, Esq., Town Treasurer of Oxford for the year 1807, from the late Samuel Campbell, Treasurer, there was a note of Amos Shumway, Jr., to pay Deborah Jack* twelve dollars and interest, amount due, $15.51.

*Deborah Whittemore [I don’t know why her surname is not that of her parents and is instead her father's first name. -ed.]

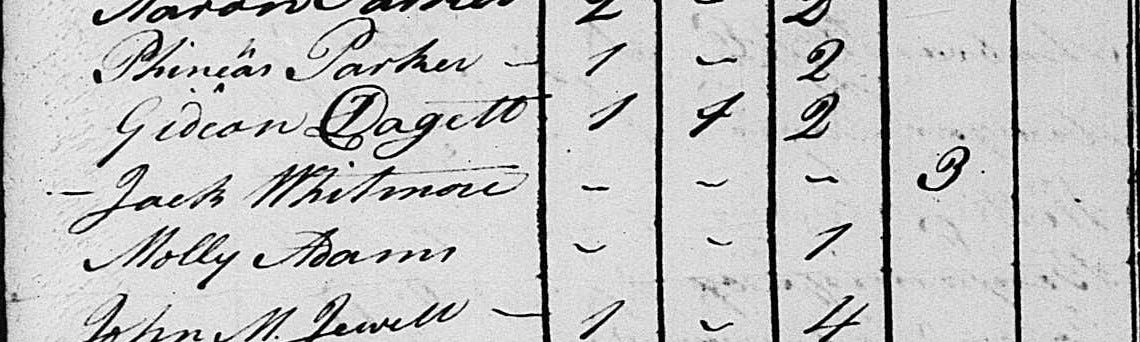

Others enslaved in Oxford

Richard Moore, Esq., owned Sharper, a slave, and sold him, 1736, by Joshua Haynes of Sudbury. Richard Moore, Jr., in 1755, owned Caesar, a slave. Moses Marcy, in 1747, owned a female slave. 1771, William Watson is taxed for two slaves; in 1775 a slave was sold as a part of his estate. . .

In a letter of Gabriel Bernon,16 the president of the French Plantations of New Oxford, to the son of Governor Dudley, October 1720,17 he writes of his losses while interested in the French plantation of Oxford, and included his servant, "negro Tom,18 who was drowned, at fifty pounds loss." This is the record of the first slave in Oxford.

Bernon, being anxious to hold possession of his French plantation in New Oxford, had placed one Cooper and a "negro Tom" to occupy the premises, "the howse and farme at New Oxford called the olde mill," the late Captin Humphrey's estate, now occupied by his descendants.

In the will of Rev. John Campbell,19 bearing the date of August 1, 1760, is the following item: "I bequeath to my son William my saddle horse and furniture, together with all that part and number of my cattle, sheep and swine that remain undisposed of in this Instrument, as also my negro servant 'Will' to be kindly used and improved and supported by him during his natural life and at the Expiration thereof to give him decent Christian Burial."

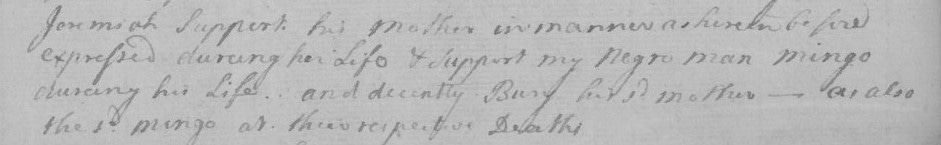

Mingo [was] a slave owned by Col. Ebenezer Learned.20 At the decease of Col Learned, Mingo was to be kept in the family. This item in the will of Col. Learned: "And support my negro man Mingo during his life and decently bury said Mingo at his death."

In 1771, on a town list for Oxford, Mr. Thomas Davis is taxed21 for a “servant for life," one of the four negro slaves then owned in Oxford.

Mary, a daughter of Mr. John Davis of Oxford, on her marriage to Major Nathaniel Healy of Dudley, Jan. 3, 1788, became the mistress of “Violet," once a slave, who the Healy family had owned. Violet had been taken from the African coast and brought to New England with a brother when children and sold. When surprised by their captors they were watching the rice fields to keep off the little monkeys from committing their depredations on the rice.22

Freeland, Mary de Witt. 1894. The Records of Oxford Mass.; Including Chapters of Nipmuck, Huguenot, and English History, Accompanied with Biographical Sketches and Notes, 1630-1890, with Manners and Fashions of the Time. Albany N.Y: J. Munsell's Sons.

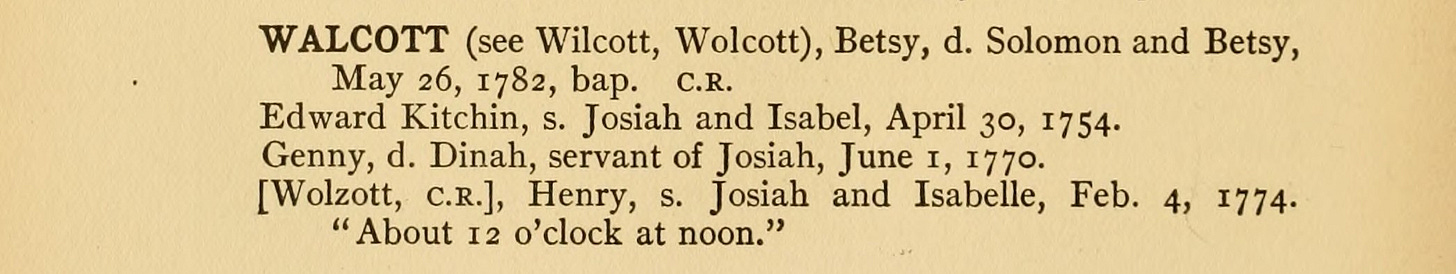

Vital Records of Oxford indicate that Dinah’s daughter Genny was born in the Walcott home in 1770, which disputes Dinah’s 1776 arrival. Or the author is fusing the narratives of two women named Dinah into one person.

Vital Records of Oxford, Massachusetts, to the end of the year 1849. Worcester, MA: F. P. Rice, 1905. pp 116-117.

From 1757-1761, Duncan Campbell lived in a home now the ell section of 2 Lovett Rd in Oxford. It’s unclear if Campbell enslaved people during this time. source: MACRIS

Always reject and interrogate “faithful slave” narratives.

Making chocolate was common for people enslaved in Boston’s chocolate houses. Much has been written on this subject. I’m unaware of other mentions of enslaved chocolate production in hinterland communities such as Oxford.

The “chocolate” here is a drinking chocolate served as a coffee or tea alternative.

Dinah was responsible for food preparation and child care.

What to make of Dinah’s “love and ‘duty’?” This is surely included to support the “faithful slave” propaganda. However, there are examples of white families—such as Abigail Adams and Phebe Abdee, and Elizabeth “Mum Bett” Freeman and the Sedgewicks—who show familial affection for enslaved (and then freed) women even when they maintain structured inequality in the relationship. Compare this to the Southern “mammy” stereotype.

After Dinah’s “long life of faithful service,” she is a “wench” and it’s Samuel Campbell that gets paid.

These embroideries sound incredible. Do they still exist? Where?

According to Dr. Daniel Livesay, and I am paraphrasing liberally, it was common to exaggerate the age of the enslaved or formerly enslaved as a way to say, “Look at how well we treat Black folks! They live to be a hundred, therefore they are better off with us than in the South, the West Indies, or Africa.”

Dinah’s children were born in 1770 and 1775. If the 1829 age of 100 were correct, it would mean that Dinah and Boston started their family when Dinah was age 41. This seems unlikely and undercuts the notion that Dinah died at age 100.

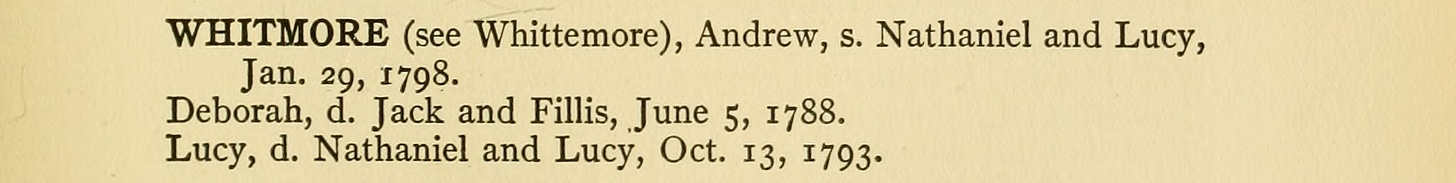

Contradictory to Freeland’s narrative, Deborah appears to be born in Oxford. Vital Records of Oxford, Massachusetts, to the end of the year 1849. Worcester, MA: F. P. Rice, 1905. p 119.

Where is Freeland getting the details of Phylis’s capture and auction?

While Oxford founder Gabriel Bernon is well-studied as a Huguenot and Rhode Island merchant, he appears to be under-studied as a slaveholder and slave trader. Bernon once enslaved Emmanuel “Manna” Bernoon, who opened Providence’s first oyster and ale house. See also: Guide to Manuscripts at the Rhode Island Historical Society Relating to People of Color, which notes that in 1714 Bernon gifted an enslaved Black woman to James Honeyman’s daughter.

This letter appears to reside in the Gabriel Bernon Papers housed at the Rhode Island Historical Society. This transcription does not mention the drowned servant's first name or racial identity.

Freeland mentions Negro Tom earlier in a 1707 letter transcribed here.

Worcester County Probate Files. Case # 9803. online: FamilySearch.org.

Worcester County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1731-1881. Case # 36615. Online: AmericanAncestors.org [Paywall]

Slave voyages rarely passed from West Africa directly to Boston. If Phylis Whittemore and Violet were born in Africa, it’s likely that they not only survived the initial Middle Passage to the West Indies or South Carolina but a second passage northward to New England.