Welcome, readers! I’ve written quite a bit about Abington, Massachusetts, at eleven-names.com. Today I add further context by examining a 1930 pageant, colonial account books, and census data. - Wayne

The Spirit of Abington

Last spring, Abington’s Dyer Memorial Library & Archives received a collection that included a 1930 program outlining Abington’s Old Home Weekend.

I was able to examine the program shortly after it arrived, and the event that caught my eye was a historical pageant titled “The Spirit of Abington,” which consisted of a series of vignettes starting in 1620 and running through post-World War I immigration.

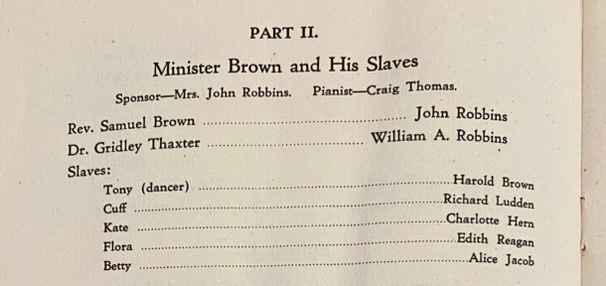

Note the title of Episode III, Part II: Minister Brown and His Slaves. This depicts a conversation between the Rev. Samuel Brown1 and Dr. Gridley Thaxter.2 The program lists a cast of non-speaking characters, including Tony (dancer), Cuff, Kate, Flora, and Betty. The names of these enslaved people are historically accurate and appear in the primary archival sources, and I’ve written about them before. These names are also lifted directly from Benjamin Hobart’s 1866 History of the Town of Abington.

Like any playbill, actors are listed alongside each role, meaning five Abingtonians played enslaved people. Being honest, it’s hard to imagine that the pageant committee a.) found five Black folks willing to perform and b.) that five Black actors wanted to play Rev. Brown’s “slaves.” So where did that leave the production? I have not seen photos of the production, but given that the 1930s were the height of blackface enthusiast Al Jolson’s popularity, and noticing that the scene ends with Tony dancing—another hallmark of vaudeville minstrelry—this was likely a blackface performance.

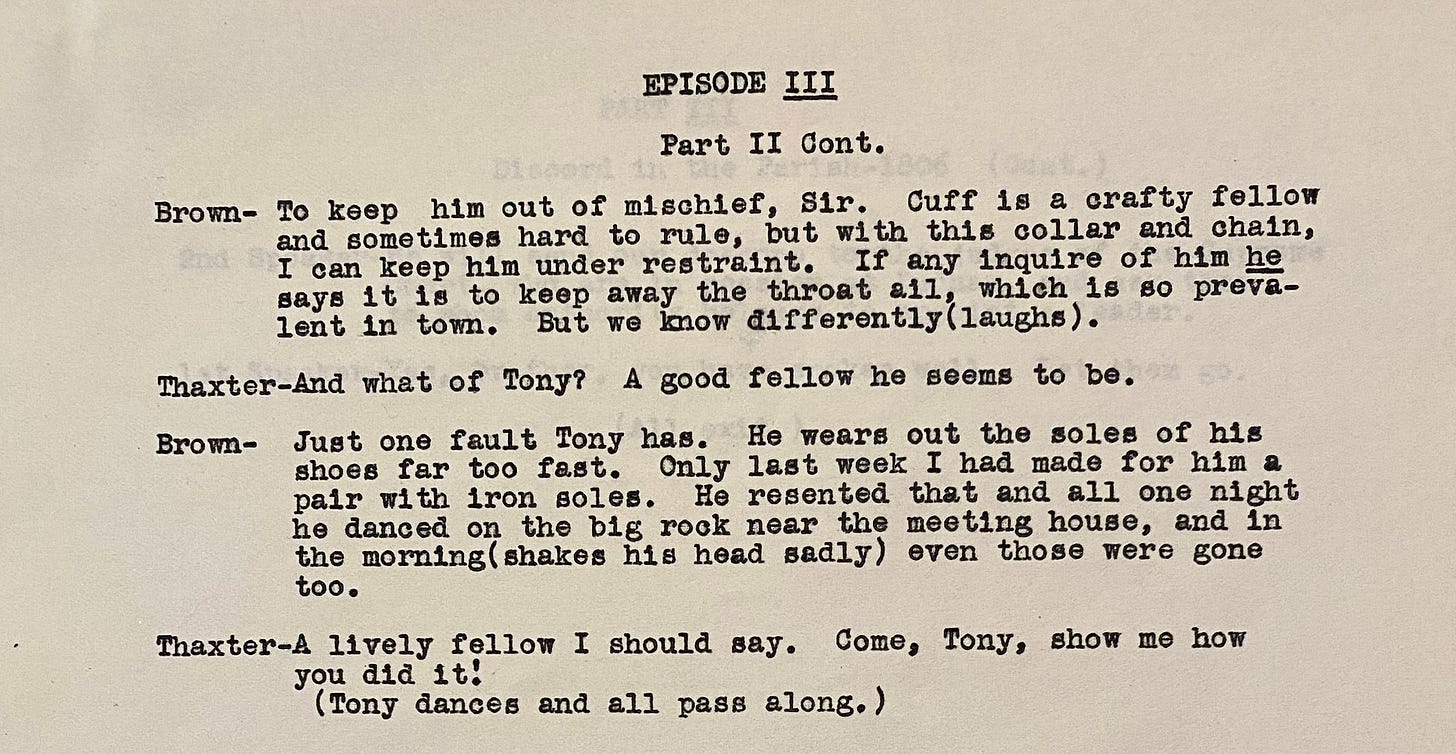

Last month, I located the pageant’s script at the Dyer—and it gets worse. Rev. Brown is praised for being a slaveholder, and he boasts and jokes about Cuff’s humiliating iron neck collar. He further laments Tony’s “fault” for wearing out his shoes; that complaint conveniently sets up Tony’s dance.

Thaxter—Whither bound this beautiful morning Brother Brown?

Brown—Neighbor Gloyd has asked for assistance in raising a new barn this day and I am taking my five slaves to aid him in his task.

Thaxter—Well done, Mr. Brown. And you are indeed rich in possession of five such valuable slaves. But for what reason does Cuff wear this iron collar? (points to collar.)

Brown—To keep him out of mischief, Sir. Cuff is a crafty fellow and sometimes hard to rule, but with this collar and chair, I can keep him under restraint. If any inquire of him he says it is to keep away the throat ail, which is so prevalent in town. But we know differently (laughs).

Thaxter—And what of Tony? A good fellow he seems to be.

Brown—Just one fault Tony has. He wears out the soles of his shoes far too fast. Only last week I had made for him a pair with iron soles. He resented that and all one night he danced on the big rock near the meeting house, and in the morning (shakes his head sadly) even those were gone too.

Thaxter—A lively fellow I should say. Come, Tony, show me how you did it! (Tony dances and all pass along.)

What strikes me about this pageant, beyond the predictable racism, is the historical memory. In 2023, the popular refrain is, “I didn’t know slavery was so common in Massachusetts! I was never taught this.” Yet, here’s a hyper-local historical pageant in 1930 that wedged a skit highlighting slavery between depictions of the arrival of the Pilgrims and the Revolutionary War. Why was slavery important for the pageant’s author to include?

The Historical Cuff and Tony

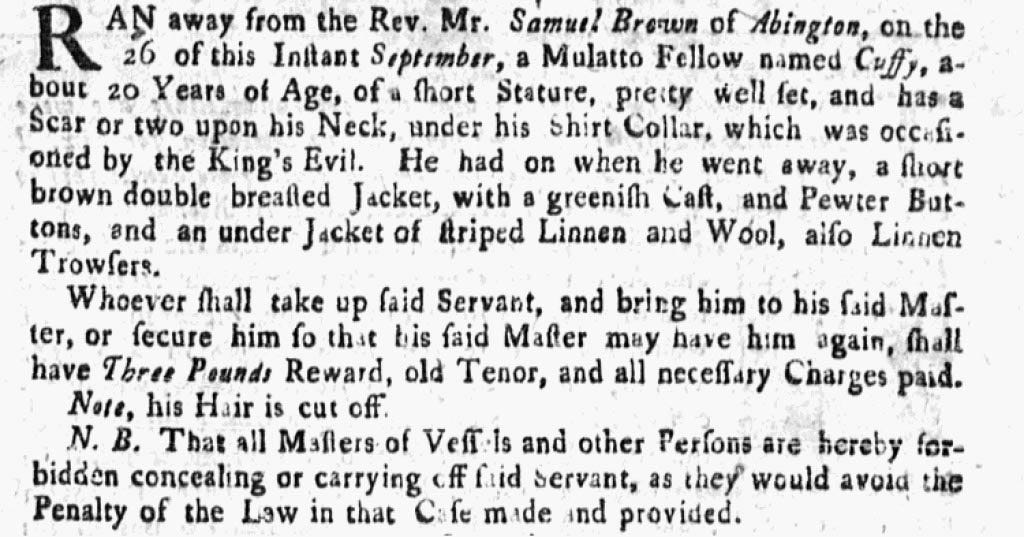

Several sources attest to the historical existence of the enslaved people depicted in Abington’s pageant. I wrote at length about Cuff, a/k/a Cuffy Rosaria, before; he is noteworthy for appearing in both a runaway ad and in Revolutionary muster rolls. Here is the 1747 ad authored by the Rev. Brown:

Tony is noted in Rev. Brown’s church diary and local oral tradition.

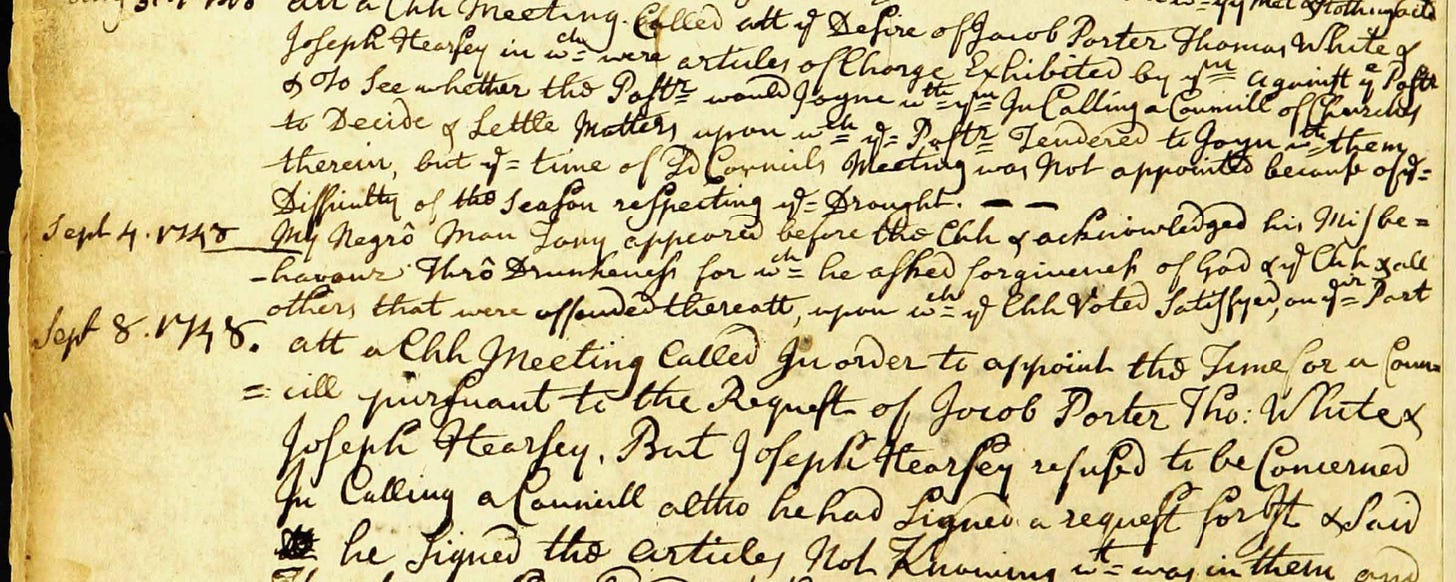

In 1748, Tony, who was admitted as a member of the Abington church in 1742, the same day as Rev. Brown’s son Woodbridge was admitted, was required to make a confession to remain a member in good standing:

Sept 4, 1748: My Negro Man Tony appeared before the [church] & acknowledged his misbehavior through drunkenness for [which] he asked forgiveness of God & [the church] & all others that were offended there at, upon [which the church] voted satisfied [and is passed].

Additionally, Benjamin Hobart’s narrative of Tony informs us that:

One of the anecdotes told of Tony's strength and agility, is, that at the raising of a forty-feet barn belonging to Samuel Norton, Esq., he jumped from beam to beam, the whole length of the building.

As in the pageant, here we see enslaved labor being loaned/hired out to labor for neighbors.3 Hobart speculates that tale of Tony’s jumping ability is exaggerated. Reading further, Hobart relates of Tony’s shoes that:

His master complained of his wearing out his shoes too fast, and got him a pair shod with iron, telling him he thought they would last him longer. Tony put them on and danced all night on a flat rock, and wore them entirely out. In the morning he carried them to Mr. Torrey4, and said he had had a dance last night and wore them all up-iron bottoms did not last so long as leather ones.

Speaking of Shoes. . .

Content warning: racial slurs in the image below.

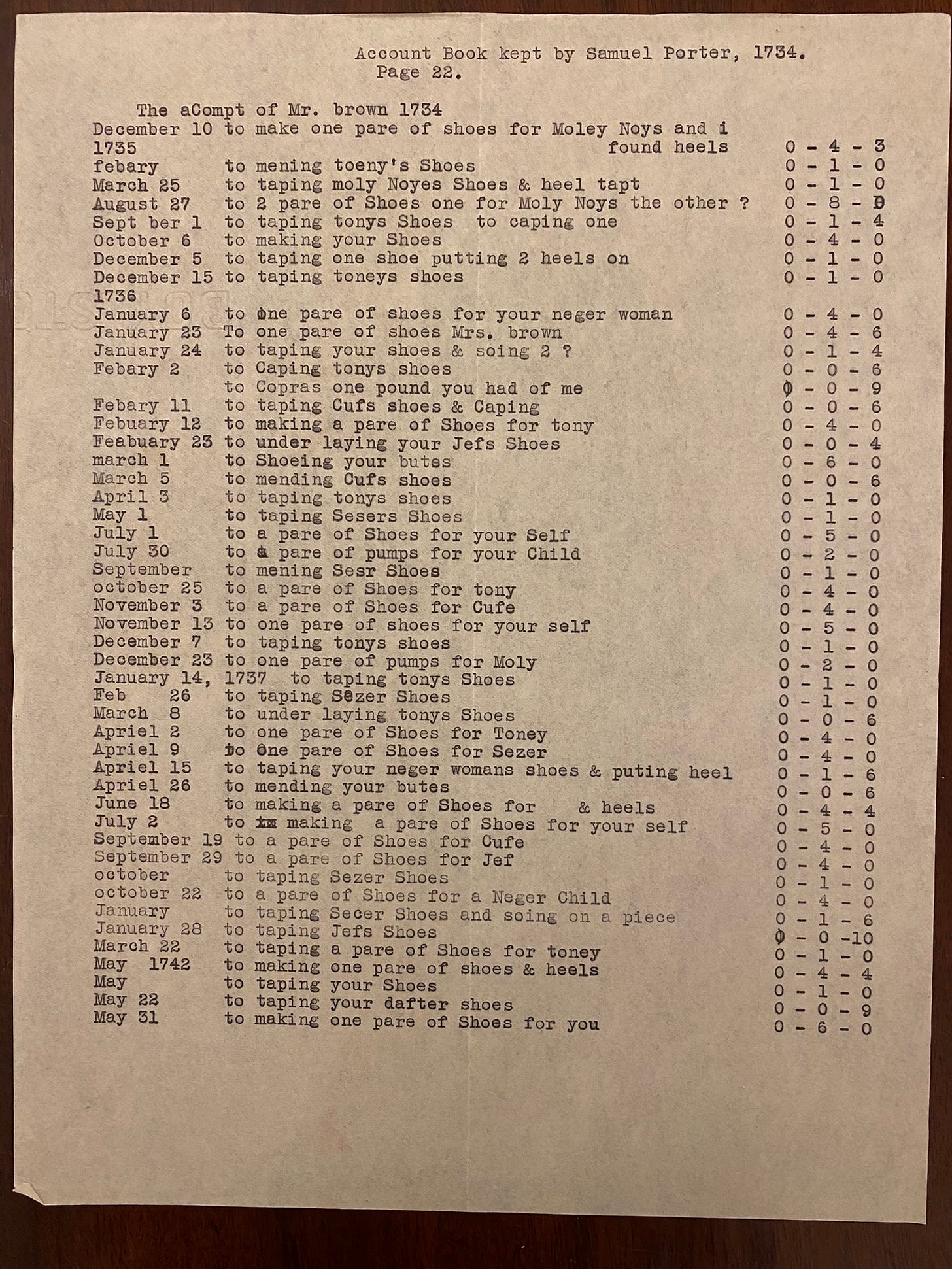

In the possession of the Dyer Memorial Library and Archives is the account book of Samuel Porter, a cobbler. Upon spying a typescript of Rev. Brown’s account for 1734-1736, I noticed that the page shows 47 transactions, with 27 noted for repairs on the shoes of people Brown enslaved (57%). Conspicuously, 12 of the repairs (25%) were made on Tony’s shoes, meaning the data supports the folklore.

Tony’s small act of resistance in the 1730s, the destruction of his shoes, became so legendary that it echoed into a historical pageant 200 years later and three centuries later rippled into an email newsletter/blog in 2023.

Slavery in Abington before it was Abington

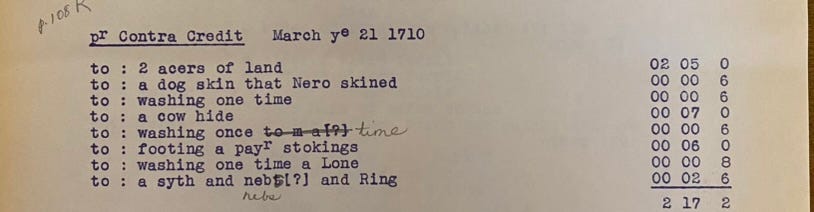

Another transcribed account book in the Dyer’s collection is that of Daniel Axtell. In the years before Abington’s 1712 incorporation, tanner Axtell records his transactions, including times that he rented out his enslaved men, Pompey and Nero. One line item accounts for “a dog skin that Nero skined [sic].” Axtell was tanning more than just cow and horse hides, and the price was sixpence.

Slavery in Abington by the Numbers

In 1754, Gov. William Shirley ordered a colony-wide slavery census of all enslaved people aged 16 or older. The results for Abington were as follows and do not account for the known enslaved children in town:

Enslaved Males: 5 | Enslaved Females: 2 | Total: 7

There was also a colony-wide census in 1765 and in addition to accounting for all the white people, it included male and female categories “Negro” and “Indian.” The census does not indicate freedom status. The results:

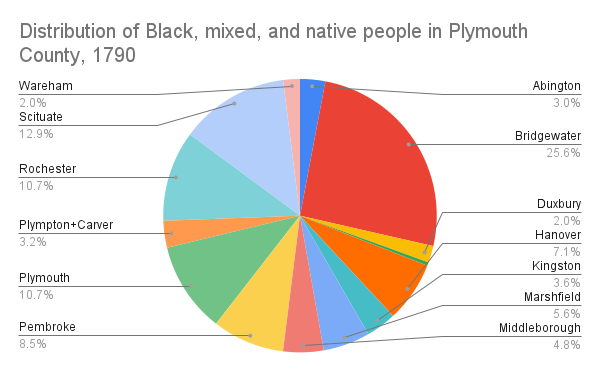

So, how does Abington stack up to the rest of Plymouth County that year?

Further interesting is the 1790 census. It’s oft repeated about this census that Massachusetts was the only state not to report enslaved people. But just because people of color were not recorded as enslaved didn’t mean they were free from involuntary labor. Abington’s population of color, according to the census, consisted of 15 people of color spread out over eight white households with a total population of 1,424.

. . .to be continued.

Enslaving Minister of the Week: the Rev. Samuel Brown of Abington.

Dr. Gridley Thaxter existed. He was a naval surgeon and one-time POW during the Revolution. He moved to Abington in 1783, the year that slavery was ruled counter to the Massachusetts Constitution. He arrived from Hingham with his new bride Sarah Lincoln, daughter of Gen. Benjamin Lincoln. Also in tow was an enslaved man previously enslaved by General Lincoln, Francis/Frank Bootman, who was perhaps a part of Sarah’s dowry. What’s ahistorical in “The Spirit of Abington,” besides the painfully lame dialogue, is that Samuel Brown died in 1749, 54 years before Thaxter’s arrival and seven years before his birth. Worth mentioning: the Hingham Historical Society recently acquired the Gen. Benjamin Lincoln House.

Gloyd and Norton appear to be interchangeable between the pageant and Hobart’s text, but it shows, along with the Axtell document, that it was common for slaveholders to hire out enslaved people to neighbors for day labor. In addition to Rev. Brown, the Nash family, who were the local housewrights responsible for constructing the first two iterations of Abington’s church, were slaveholders. This raises the question: what amount of enslaved labor was used to construct the first two meetinghouses?

Notorious Abington enslaver, Squire Josiah Torrey.