Greetings, readers. On Monday evening, the Roxbury Historical Society and the Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry of Roxbury presented a landmark report titled Race & Slavery At The First Church Of Roxbury: The Colonial Period (1631–1775), authored by Harvard scholar Aabid Allibhai. Download and read the report here.

As I mentioned in Monday’s newsletter, which contains the story of Joseph Dudley trafficking an African boy from a pirate ship to his son Paul, ENP began by examining the Dudley family’s ties to slavery. Therefore, I wanted to introduce new readers to these original stories. Today’s excerpt gives details on a coachman named Brill.

The next original newsletter will review Allibhai’s report and highlight a new name uncovered by Aabid’s work. - Wayne

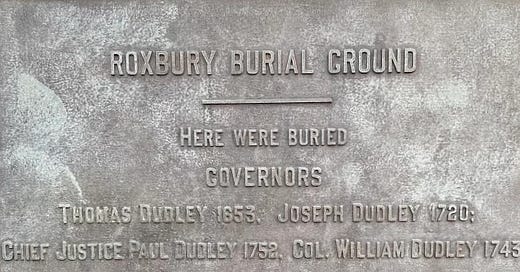

Gov. Joseph Dudley (1647-1720) was a colonial Governor of Massachusetts whose family were multi-generational residents of Roxbury. He played a key role in the Dominion of New England (1686-1689), and served in the Province of New York government. He then spent 8 years in England as Lieutenant-Governor of the Isle of Wight, including a year as a Member of Parliament. In 1702, Dudley returned to New England as governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and Province of New Hampshire, which he held until 1715.

Brill

Rebecca Tyng Dudley died in 1722, two years after her husband, Governor Joseph Dudley, bequeathed (.pdf pg 402) to her his vaguely-defined and unquantified “servants”; Dudley noted neither the status–indentured, Negro, or Indian–nor number of servants. Fortunately, UW Madison historian Gloria McCahon Whiting notes in a 2020 journal article that Rebecca Dudley’s will specified that Brill, her “negro servant,” would be freed within a year of her death–that is unless her children required his services.

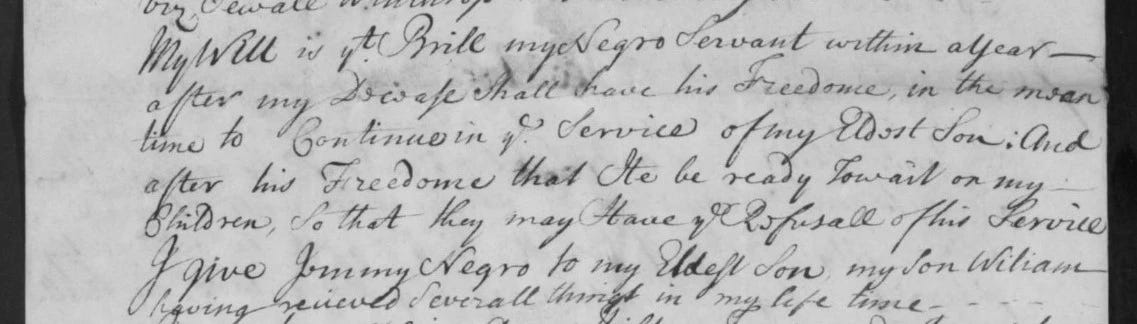

Through the miracle of digital collections, we can see an image of Rebecca’s original will above. In addition to Brill, the man Whiting leads us to, Rebecca further specifies, “I give Jimmy Negro to my eldest son.” Paul was Rebecca’s oldest son, the Dudley who conspired with his father to traffic an enslaved boy from a pirate ship. I’m still searching for more details about Jimmy, but as luck would have it, the Massachusetts Historical Society’s Collections contain two credible witnesses to Brill’s life in bondage: Salem Witch Trial judges Samuel Sewall and Waitstill Winthrop.

The first record I came across is when prolific diarist Samuel Sewall noted at least 2 encounters with Brill in 1713. On February 16th, “Brill calls just at night, From the Govr enquires of my Son’s Wellfare,” and on February 25th, “Brill Comes to Town, and acquaints that the Govr was taken with a sore Fit of Gravel last night so can’t be at Council today.” (Sewell pp 371, 372).

Joseph Dudley served as governor from 1705-1715, so we apparently have the same servant Brill in Rebecca Dudley’s 1722 will relaying messages to Samuel Sewall nine years earlier. In later diary entries, Sewall paints the picture of Brill as Governor Dudley’s coachman. On July 5, 1714, Sewall notes a time when the governor’s chariot failed at B. White’s and that “Brill could fetch the coach.”

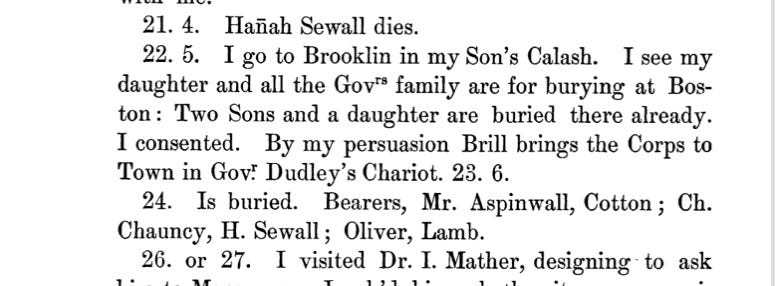

In October 1719, Sewall records that his granddaughter Hannah Sewall, who is also the granddaughter of Governor Dudley, dies and Brill is the one to transport her body: “I go to Brooklin[e] in my Son’s Calash. I see my daughter and all the Gov’s family are for burying at Boston: Two Sons and a daughter are buried there already. I consented. By my persuasion Brill brings the Corps to Town in Gov Dudley’s Chariot.”

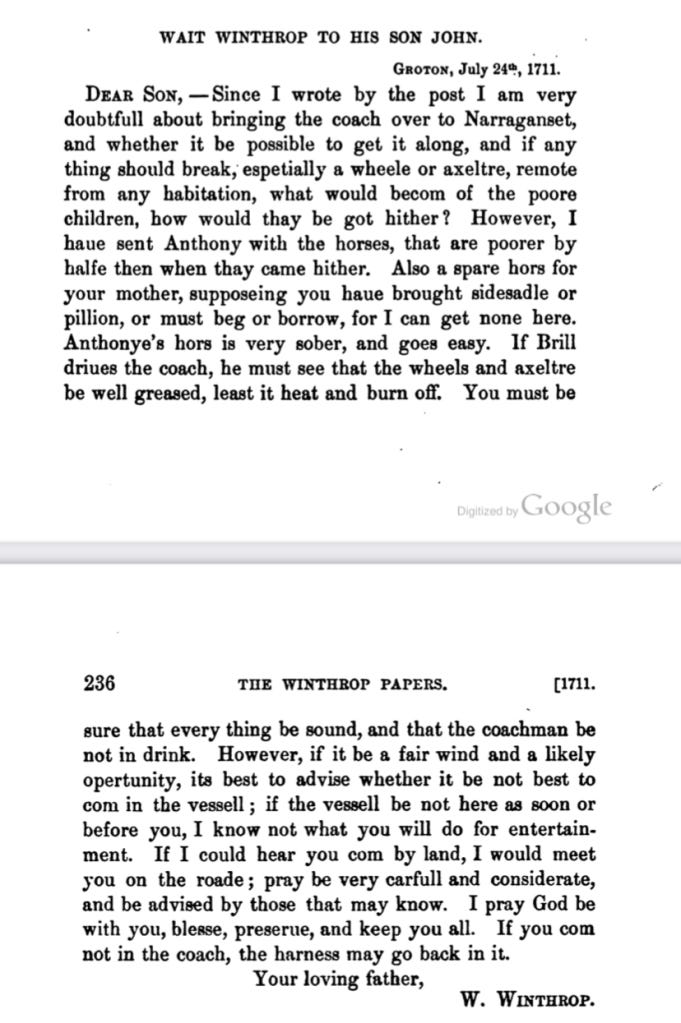

Brill seems to be well-known in greater Roxbury; he not only appears in Samuel Sewall’s diaries but is attested to earlier in 1711 letters from Waitstill Winthrop to his son John (husband to Ann Dudley and son-in-law to Governor Joseph Dudley). Waitstill, writing from Connecticut, dispatches a series of letters to dissuade John and his family from visiting from Boston. In a July 24th letter, Winthrop warns, “If Brill drives the coach, he must see that the wheels and axeltre be well greased, least it heat and burn off. You must be sure that every thing be sound, and that the coachman be not in drink.” Winthrop confirms that this is our man Brill when Winthrop writes two days later by asking, “I know not how you will all com in the Governor’s coach and if a wheele or axltre brake in the woods, how will the children get to any shelter?”

The last entry I’ve found mentioning Brill before Rebecca Dudley’s will is Judge Sewall noting that on March 30, 1720, Governor Dudley is on his deathbed and “Brill came to Town in the Morning; Put up a Note at [Rev. Benjamin] Colman’s [house].” Joseph Dudley died three days later.

I can’t find any narrative of Brill’s life using Google, Google Books, or Google Scholar. It’s safe to say that Joseph and Rebecca Dudley enslaving a Black coachman for 11 years is not a well-discussed fact and it’s exciting to share this with readers of this site.