Dear readers: this evening, the Roxbury Historical Society and the Unitarian Universalist Urban Ministry of Roxbury presented a blockbuster report titled Race & Slavery At The First Church Of Roxbury: The Colonial Period (1631–1775) authored by Harvard scholar and Du Bois Institute fellow Aabid Allibhai. Read the reporting on this study at The Boston Globe [paywall].

The first Eleven Names essays were about the founding Dudley family of Roxbury. I’m proud to say Allibhai cited my work several times and pushed it forward. Also, Aabid reached out to thank me, which was quite generous and gratifying.

To mark the release of the report, there will be three newsletters this week. As a refresher, I am re-printing two stories—tonight, the story of Paul Dudley trafficking an enslaved boy off of a pirate ship, and on Wednesday I’ll run a story about Joseph Dudley’s coachman, Brill. Then, later this week, I’ll publish an original essay that will discuss the origins of the Eleven Names Project, give a brief review Race & Slavery at The First Parish, and highlight the find that made me exclaim out loud “Holy s***!” (Yes it was that amazing, and yes it’s about the story below.)

Definitely read Allibhai’s excellent work for yourself (I’ll share it when it becomes available online.) Also, can I ask a favor? If you find yourself talking about this report with friends or colleagues, would you recommend to them my work on the Dudleys? Or perhaps forward this email? ENP is growing, but I still need your help! Thank you for reading. - Wayne

Paul Dudley was the son of Gov. Joseph, the brother of William, and the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts colonial government. Digging into archival records, we find two stunning examples of Judge Paul Dudley enslaving Black people 40 years apart.

The Dudleys, Pirates, and Clandestine Slave Trade

Looking in a “Calendar of State Papers” from a London archive published in 1916, we find a receipt showing in 1705 a “Negro boy taken from the pirate John Quelch and sold to Paul Dudley for 20 [pounds], the highest bid at William Skinner’s Tavern Boston Oct 6.” This record is enclosed in Dudley’s response to John Colman’s complaint to the Council of Trade and Plantations in London. Colman was part owner of the vessel Charles, a privateering ship granted license by Governor Joseph Dudley. The crew of the Charles mutinied and attacked ships from Portugal, a British ally, and, upon return, the pirates were tried and executed.

What happened to the rest of the ship’s booty I am not sure of, but John Colman is quite upset that the “negro boy” he viewed as his property was funneled by Governor Joseph Dudley to his son Paul and sold to him for the very cheap price of 20 pounds.

Colman writes to London requesting “[a] bond for the 50 [pounds] Governor Dudley squeezed out of us was given to his son, for the Governor. The sale of the negro boy was clandestine, for there had not been due notice there of, etc, etc.” Dudley is dismissive, characterizing Colman’s complaint as a “foolish and groundless aspersion,” further responding “[t]he sale was public and there was another negro sold at the same time at the same price…The Judge never asked 5 p.c. for the condemnations of that prize…as Receiver [Colman was commissioned as Receiver General of Massachusetts] he has, for the most part, himself bought the prizes that have been imported to this place…”

We don’t know if this “negro boy”–whose age is unknown–was originally enslaved by the British sailors or if he arrived in Boston “as plunder from piratical raids,” as Wesley Fiorentino puts it in the highly-recommended article about Quelch linked above. But we do know that Paul Dudley purchased an enslaved African from this ship and it’s likely his father the governor facilitated this, perhaps in a clandestine, extra-legal manner.

But the dubiousness doesn’t stop there. The Massachusetts Attorney General at that time argued for an immediate admiralty trial, the first of its kind outside of England. The Attorney General, as it turns out, was also the prosecutor who won a conviction at the trial. His name? One Paul Dudley.

If that weren’t eyebrow-raising enough, legal scholar Stephen M. Sheppard notes:

Joseph Dudley appointed Paul to a three-man commission for seizing pirates and their treasure, along with future allies Nathaniel Byfield and Samuel Sewall. The commission took to its task with bravado, in some cases directing the attack force that rounded up the pirate bands. As attorney general, Dudley acted also as prosecutor and attracted quite a reputation from these trials, the most notorious of which was of Captain John Quelch, a strayed privateer. On the other hand, there was also the complaint that the trials (with the inevitable hangings to follow) were nothing more than judicial murder.

- Stephen M. Sheppard, Paul Dudley: Heritage, Observation, and Conscience (2000. p. 8) St. Mary’s University School of Law

Pure shadiness. What could possibly go wrong when the official deciding who to prosecute for piracy is also on the commission in charge of seizing and divvying the ill-gotten “prizes” and, by the way, he is the governor’s son? This could be another hilarious iteration of entrenched Boston political corruption if there weren’t commodified humans on the auction block.

How many enslaved Africans did the Dudleys traffic through this pirate commission for their own—and other Dudley family members—gain? How many of them were children? And what could we learn about these enslaved people from the records? These are burning questions.

Guinea’s Baptism

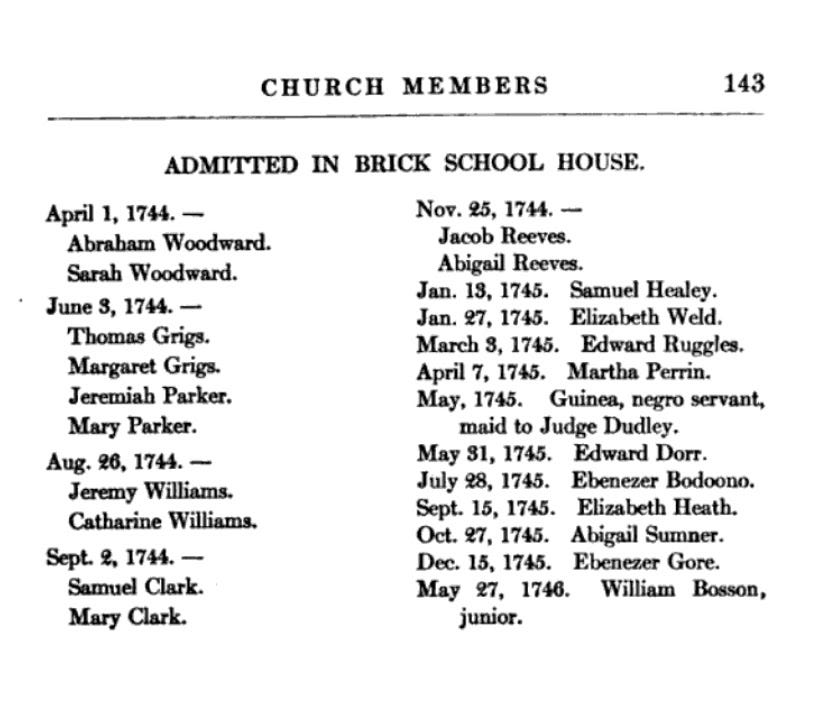

Forty years later we have another record of a Black person enslaved by Paul Dudley. In the History of the First Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1630-1904 under the heading “Church members admitted in brick school house“ – the brick school house was where the Roxbury congregation worshiped after the third meeting house burned—we find an entry “May 1745, Guinea, negro servant, maid to Judge Dudley.” Guinea’s baptism is recorded on the previous page, and she is one of the numerous examples of enslaved Africans being baptized church members in colonial Massachusetts. One of the first enslaved Africans to gain church membership was Dorcas the Blackmore, who joined the Dorchester church of her enslaver, Israel Stoughton. It’s worth noting that membership did not mean that an enslaved person was released from slavery.