"My two boys, whom I obtained with my sword and my bow" - Capt. John Williams

Chronicling Dick Morey & a CT Minister who mortgaged an enslaved man

Welcome! Would you take a moment to forward this email or recommend Open Notebook on a social channel? Your help is appreciated! - Wayne

JP’s Loring Greenough House, Dick Morey, and J. L. Bell

Attentive Open Notebook readers may remember that Boston Archeology initiated an excavation at Jamaica Plain’s historic Loring Greenough House. A Facebook post highlighted the connection to slavery at the 1760 mansion. It probed the blurring and legal manipulation of gradual emancipation in the burgeoning Commonwealth after slavery was ruled counter to the state constitution in 1783. The centerpiece was two original documents that detailed the 1785 sale of a five-year-old multiracial boy named Dick and his 1786 reclassification by the selectmen of Roxbury as an “indenture,” which is perhaps more accurately described as “term slavery.”

Beyond the primary documents and a visit to the Loring Greenough house, the best resource to explore Dick Morey’s life is J. L. Bell’s Boston 1775 blog. First, Bell sketches the circumstances in Boston that funneled once-enslaved Dick into the indenture system in Dick Morey “in the Capacity of a Servant.” Next, Bell looks at Dick’s original enslaver John Morey, his family’s backstory, and the conditions that precipitated Dick’s sale. Then, after I sent Bell a 1798 runaway ad placed by David S. Greenough, Bell gives a close read of the ad and surfaces new insights into the life of Dick, now Dick Welsh. Lastly, this close read segues into the fourth entry in the series, an astute contextualization of rewards for runaway servants in 1798.

If anything, the initiative taken by the Loring Greenough House and Boston Archeology, and Bell’s follow-up investigation, has given the public tools to understand better how Massachusetts navigated the murky waters of gradual emancipation.

Origin Story

Ever wonder how the Eleven Names Project got started? I wrote a guest post for The Partnership for Historic Bostons. Check out Pulling the Thread of Slavery.

Probate File of the Week: Capt. John Williams of Scituate, Mass.

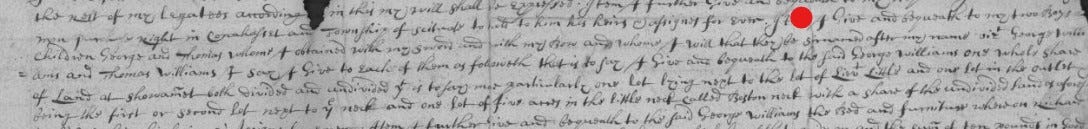

“I Give and Bequeath to my two Boys and children George and Thomas, Whome I obtained with my Sword and with my Bow and Whome I Will that they be sirnamed after my name viz George Williams and Thomas Williams. . .” - Capt. John Williams, 1694

In a previous newsletter, I highlighted the 1695 probate file of “Will Indian.” I noted that this was the earliest-indexed probate file of a non-white decedent in the three Plymouth Colony counties. So why was Will participating in English legal and property ownership systems? And what to make of land described as “given to him by Capt John Williams”?

Although the record is vague, Will was likely captured during King Philip’s War (c. 1676) by Captain Williams, alongside at least two young boys.

Captain Williams’ Scituate home is remembered as a landmark because it was a garrison for English settlers during the war. Today it still stands as a restaurant. When Indian forces sacked and burned Scituate, Williams was not among those garrisoned in his home; his 30-man ranger unit was patroling Middleborough and harassing King Philip’s encampment at Assowampsett.

Captain Williams and his Scituate men later attacked Mount Hope, Rhode Island, during King Philip’s last stand, where they assaulted Philip’s forces from the flank opposite Benjamin Church’s notorious regiment. Mount Hope, originally known to the English as Massasoit/Ousemequin’s seat, is also where Ousemequin’s son Metacomet (King Philip) kept his home and headquarters. Here, Metacomet was killed by an English-allied native named John Alderman. Metacomet's body was decapitated, mutilated, and then his head was displayed on a pike in Plymouth’s town square opposite the First Church for twenty years.

The genocidal King Philip’s War accelerated the exploitation of chattel slavery in New England. After the war, a thousand Indian men were sold to foreign slave markets, and roughly the same amount of Africans were enslaved in this region. Additionally, about 20%-40% of the surviving Indian population was held in bondage by white colonists. The Indians in John Williams' household may have been trophies of war-time victory.

Williams appears in many seventeenth-century records. For one, his headstone is a fine example of early New England stone carving, his estate was amongst the most impressive in the Old Colony, and he was a prolific litigant in Plymouth court—even by seventeenth-century standards.

Both Williams’ niece Deborah Barker and his wife Elizabeth (Lathrop) Williams accused Williams of abuse. Williams made a countercharge against his wife as being an unfaithful “whore” and claimed that the child she recently delivered was not his. Elizabeth eventually prevailed; she won the right to separate from Williams, to one-third of his estate, and to monthly support payments of £10. The record is not clear on Elizabeth’s child, and the child does not appear in Williams’ probate file.

Williams further appears in court to press trespassing charges against his neighbors and to answer charges that he sold cider and rum to local Indians. Williams is also the Scituate slaveholder previously discussed by Open Notebook who in 1696 pressed burglary charges against a man he enslaved named “John Negro”, who was sentenced to “stand at the gallows an hour [&] burnt in the hand with the letter B.”

Willliams’ probate inventory values Indian men Will, George, and Tom at £60. However, no people of African descent appear in this document, and John Negro’s fate remains unclear.

But what of Williams’ legacy to Will? And what did John Williams bequeath to his “children,” whom he “obtained” with his sword and bow, beyond his surname? Below is a (mostly) accurate transcription of some items in Williams’ last will and testament.

I Give and Bequeath to my two Boys and children George and Thomas, Whome I obtained with my Sword and with my Bow and Whome I Will that they be sirnamed after my name viz^ George Williams. . . and Thomas Williams.

[to] George Williams. . .one whole share of land at Showamet. . .one lot of five acres in the little neck called Boston. . .the Bed and furniture whereon Richard Cox usually Lodgeth. . .one of my Guns which he shall choose, my Black horse which he useth to Ride on, and the sum of twenty pounds. . .

[to] Thomas Williams. . . my corne mill and lands in Middleborough. . . one whole share of land at said Showamet. . .and one five acre land in said Boston. . . the sum of twenty pounds. . .the bed he usually lodges on with the furniture belonging to it. . .the mare usually called his and her [colt]--and two cows.

[to] my servant Will. . .the bed and furniture whereupon [tattered], one horse, and one half a share of land at Showamet which I purchased of Daniel Hicks. . .one half a share in the undivided land of said Showamet. . five acres in the little neck called Boston neck.

I hereby set free my said boys George Williams and Thomas Williams and my said men servants Thom Bayler and Will; I commit the oversight of my said boy Thomas Williams to my friend and Neighbour Joseph Woodworth of Scituate and appoint him guardian.

The Showamet lands Williams referred to were in Swansea not far from Mount Hope.

Flippantly, Williams referred to our current state capital as “that little neck called Boston,” as if he anticipated Scituate was instead destined to be the proverbial hub of the universe. And it appears that he bequeathed 15 acres to his captive legatees in Boston. What happened to these lands and what stands on these properties today? Comment below if you have any leads.

It’s also interesting to note that Williams categorized Will as a “man servant” and George and Thomas as “my boys.” I wonder what the age difference was between Will and his younger brethren, and if any of the men were related? Also, a guardian was appointed for Thomas Williams, indicating that he was younger than 21 years old. The will was probated in 1694, and King Philip’s war hostilities ended in Southern New England in 1676. If Thomas was kidnapped as a result of the war, then he was captured as an infant or a toddler.

What do we make of these bequests? Williams’ probate file does not acknowledge surviving genetic children. And while Williams’ bequests may be evidence of affection held by the old captain for his captives, he was also legally responsible for their support. If these men were left in poverty, assuming that they stayed in Scituate and did not join a tribal community, it would be the town's responsibility to support Will, George, and Thomas. And if Scituate found themselves with three paupers to support, it would be within the town’s rights to sue Williams’ estate for money to support the men. By writing bequests to these men, Williams remains in control of how his estate supports his former bondsmen.

What’s more, we must consider that Captain Williams may bear responsibility for the deaths of these men’s parents and family. Or perhaps the two children were not orphaned and were stripped from their mothers’ care. Furthermore, these men were forced into 18 years of bondage that they did not agree to and at least two of them were too young to communicate and consent to such an arrangement. And that’s before we consider the cruelty of deeding Indian men land that was Indian land in the first place. If learning about the legacies that John Williams’ left his Indian “children” and “man servant” inspires an urge to grant John Williams a redemption arc, resist it.

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. Peter Pratt

According to tradition, the Rev. Peter Pratt of Sharon, Connecticut, facing financial trouble, mortgaged an enslaved man. The practice of mortgaging enslaved people was common in southern states, but it appears to be rare in the north. This mortgage illustrates how slavery was not just about labor; it was nakedly capitalistic. Enslaved bodies offered opportunities to store, grow, and transfer wealth and capital.

Also not a good look: the fact that the author wonders if the man enslaved by Pratt is the same man enslaved by another minister named Lee.

Essential Links

The Old North Church, a Boston landmark, reckons with its role in slavery, WBUR

Which Native American tribes live, or once lived, in present-day Rhode Island?, The Newport Daily News

The Grimkes: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family, WCVB

Hartford's North End: The Making of an African American Community, Connecticut by the Numbers

Tensions arise over Native American curriculum in Connecticut schools, News 12, Brooklyn

History Cambridge has a new partnership, joining with Slave Legacy History Coalition, Cambridge Day