UPDATE: Deyaha Moussa

John Hancock's Enslaved People, Full Circle for Medford Muslims, & the 1695 Probate File of Will Indian

Welcome. I’m still locked out of Twitter after two weeks. I count on the kindness of my readers to share, forward, like, and subscribe. Please tell some friends about Open Notebook. 😀

And if you’re new, catch up on previous editions of the newsletter and visit eleven-names.com.

Update on Deyaha Moussa

In May, I wrote in The Bay State Banner that:

Deyaha Moussa was a Muslim kidnapped in West Africa, purchased in Saint-Domingue by T.H. Perkins of the eponymous School for the Blind, and who witnessed the Haitian Revolution combust. Perkins’ brother trafficked Moussa to Boston in 1793. He died in 1831 and now rests anonymously in Mattapan under a giant Celtic cross.

Deyaha’s tale is compelling and complex. I was bothered by the story for months before I unlocked a critical clue. If you’re unfamiliar with Deyaha’s narrative, it’s a six-minute read, and it’s worth checking out before finishing this week’s newsletter.

In addition to the Perkins School for the Blind, the Perkins family fortune, founded on the slave trade and opium smuggling, played instrumental roles in the birth and growth of the Museum of Fine Arts, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Boston Atheneum.

Shortly after the article was published, Dr. Christina Michelon, Associate Curator at the Boston Athenaeum, emailed to tell me that Deyaha’s story would be included in the significant reinstallation of the library’s art collection. There was an initiative afoot to “re-read” the special collections that ran parallel to a renovation. After sixteen months of construction and curation, the new installation opened last Tuesday.

For ten dollars, visitors can explore the first floor of the five-story private library. Curious to see how Deyaha appears in the reinstallation, I found myself at the Athenaeum’s 10 ½ Beacon Street location on Thursday, ready to pony up a ten-spot and continue my quest.

The sampling of the collection on view is small but beautiful and more diverse than one might imagine. I found the space overlooking the Granary Burying Ground where the Perkins family portraits now hung, a small reading room off of the Henry Long Room adjacent to the wall where the portraits were previously prominently displayed.

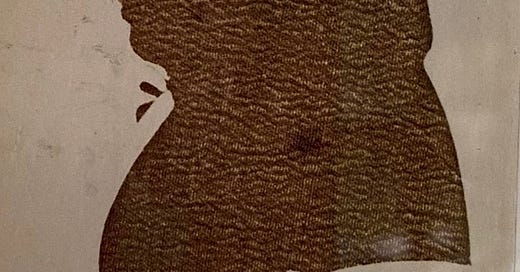

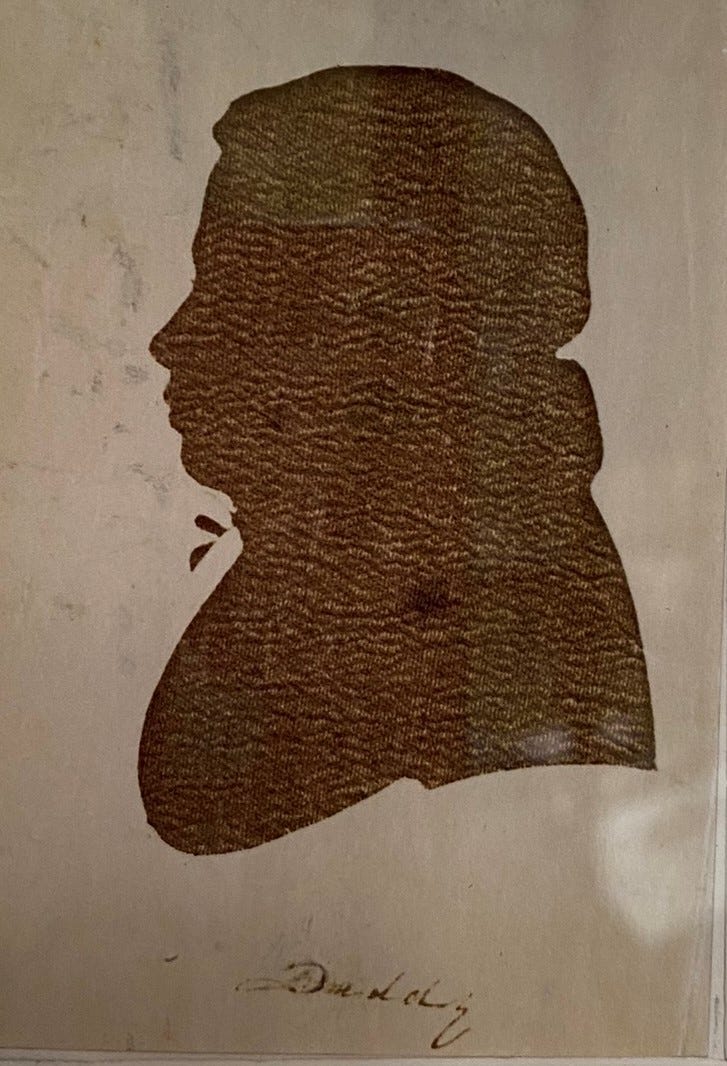

Opposite Gilbert Stuart’s seven-and-a-half foot portrait of T.H. Perkins hangs a frame that is primarily white space occupied by the matting. On the left side, centered from top to bottom, is a copy of Deyaha’s 1831 obituary. Then, on the right side, a revelation—a 2" x 4” silhouette of Deyaha with the handwritten caption of “Daddy.” It was a jolt of excitement to lay eyes on new-to-me evidence of Deyaha’s existence and life in Boston.

An interpretive panel relates that the silhouette was gifted to the Athenaeum in 2019 with the rest of the Perkins Family Papers. The panel gives further insights into Deyaha’s domestic life, stating, “Deyaha was known to most as Mousse. And the young Perkins family members, whom he helped raise, called him ‘Daddy Mousse.’” Another interpretive panel written by historian Dr. Martine Jean explains, “Deyaha’s silhouette is fascinating because it underscores his ties to bondage to the Perkinses and the family’s attempt to render that relationship invisible through intimacy by calling him ‘daddy.’ ‘Daddy’ is reminiscent of the black ‘mammy’ of Southern slaveholders.”

It was a thrill to see the only known image of Deyaha Moussa, a man whose mystery I spent months deliberating and learning about his life; if you’re in Downtown Boston with some free time, check it out.

[P.S. — If you are a fan of Roxbury icon Allan Rohan Crite, the new installation features nine of his paintings.]

Full Circle: Medford Muslims Enjoy Fruits of Wealth Generated by Enslaved Ancestors

In May, after Claire Sadar shared her DigBoston Sacred Spaces feature with me, it struck me how the topic of that piece, the Islamic Cultural Center of Medford, is now housed in a colonial mansion. These mansions were built by wealth gained due to the business of African slavery.

...So, I looked into it. The home housing the ICCM is known as the Isaac Hall house. It stands in Medford Square at the High Street and Bradlee Road corner. It was erected circa 1720 by Andrew Hall.

Hall and his family were wealthy—and slaveholders. People enslaved in Hall households appear throughout Medford's vital records. Andrew enslaved at least one girl named Phillehas who likely lived in this home.

Andrew undertook several enterprises with direct ties to slavery. One example: Hall owned a Medford distillery. He bought molasses shipped from brutal West Indian slave labor camps to Medford docks. Enslaved labor may have been used to make the Rum and its barrels. And Hall rum was likely purchased and shipped overseas to trade for enslaved people.

And the wealth spread. Hall’s sons Richard and Benjamin and his brother Stephen were also slaveholders. Andrew's sons built a cluster of five Medford Square mansions; only the Isaac Hall House survives. The Isaac Hall House is so named for Andrew's son, the captain of the Medford Minutemen; the home was a stop on Paul Revere’s ride. At the dawn of the Revolution, the brothers were still in the rum business, and Benjamin owned 17 ships circulating in the triangle trade, a/k/a the business of slavery.

The Hall family lived 1/2 mile from their friend, prolific slaveholder and Loyalist Isaac Royall, Jr. Royall was so enthusiastic about slavery that his family’s legacy, the Royall House and Slave Quarters, is a museum dedicated to propagating an authentic history of slavery in Massachusetts. In a 1776 letter, Royall indicated that Benjamin Hall offered to purchase Hagar for £100.

To bring this full circle, I'm contemplating the Islamic Cultural Center because of the thousands of enslaved West African natives who contributed to the wealth that built the Hall family houses; some of them were certainly Muslim—like Deyaha Moussa. Unfortunately, I can’t pinpoint a known Muslim burial in Massachusetts before Deyaha’s 1831 entombment. Yet, the earliest Muslims buried in New England were trafficked here via the Atlantic slave trade, perhaps as early as the 1640s. And now a home that was built as a temple to mark wealth created on the backs of enslaved Africans is today an Islamic center.

Other Boston Stops

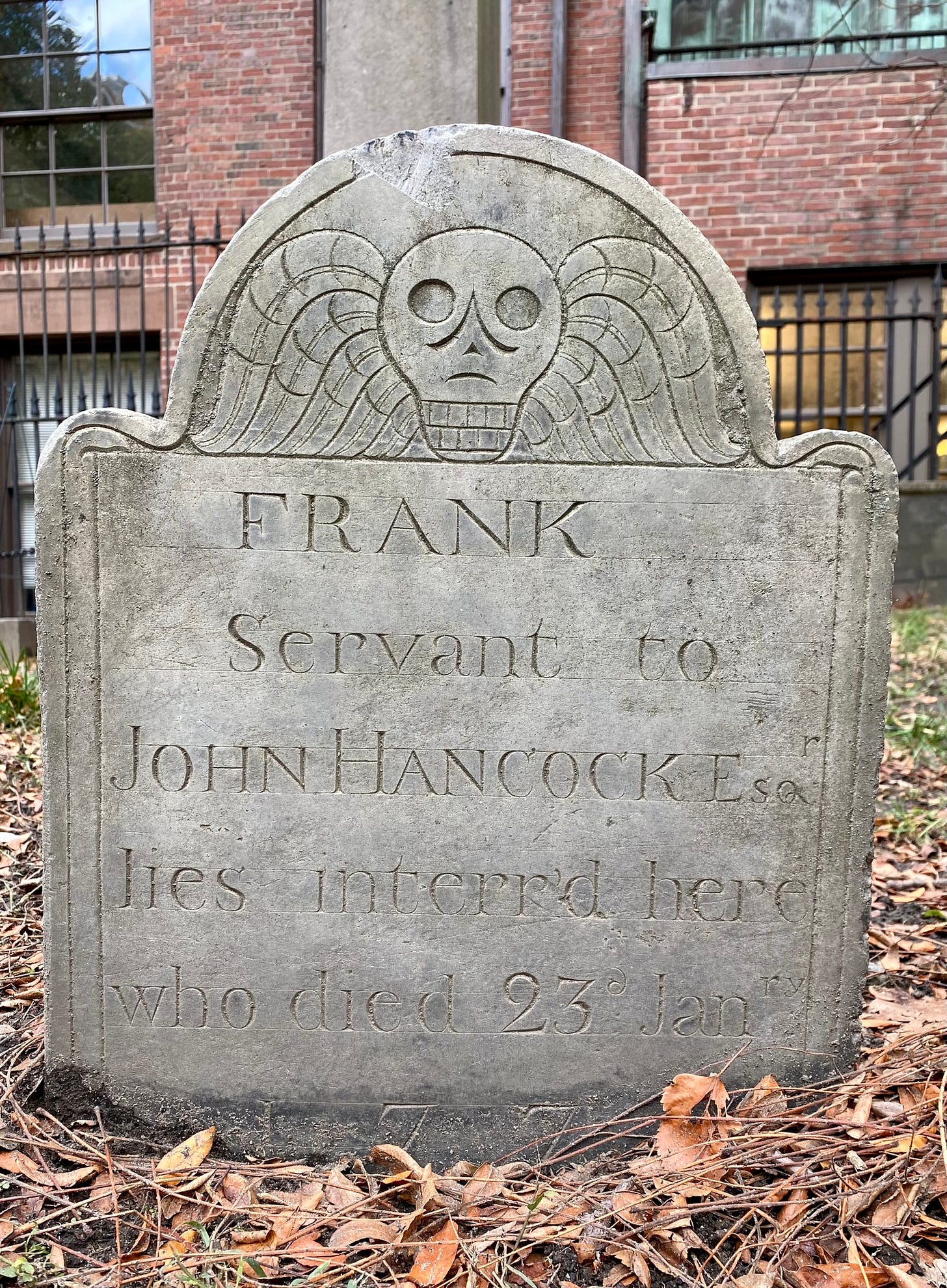

Since the Athenaeum is adjacent to the Granary Burying Ground, I snapped a photo of Frank, a man enslaved by John Hancock. On my walk to my meeting in the Charlestown Navy Yard, I stopped at Copp’s Hill Burying Ground to pay respects to Prince Hall, founder of the Black branch of Freemasonry named after him. Read about Frank and five other people enslaved by John Hancock at Vita Brevis, a blog from American Ancestors/New England Historic Genealogical Society. Also, read Yawu Miller’s piece on Prince Hall at The Bay State Banner.

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. Samuel Moody

Colonial New England towns were required to support their ministers, and it was, at times, a competitive market to entice ministers to come to a parish in need. Salary and generous land grants were part of compensation packages. Towns also provided other amenities such as firewood and food items.

The description of the parish records of York, Maine, at the Congressional Library and Archives notes another benefit sometimes afforded to ministers by their congregations: in 1734, “[a] committee of assessors was formed to raise 120 pounds and procure a slave ‘to be Imployed in his Service during the Parish's Pleasure,’ identified only as ‘the Negro man named Andrew’. In 1735, the records indicate that the committee voted to sell Andrew and hire a domestic worker instead.”

Consult the entire record at the CL&A’s Digital Archive, images 11, 14, 15, 16, and 17.

Ref: Parish Records, 1731-1739, in the York, Me. First Parish Church records, 1731-1927, RG5392. The Congregational Library & Archives, Boston, MA.

Probate File of the Week: Will (Indian)

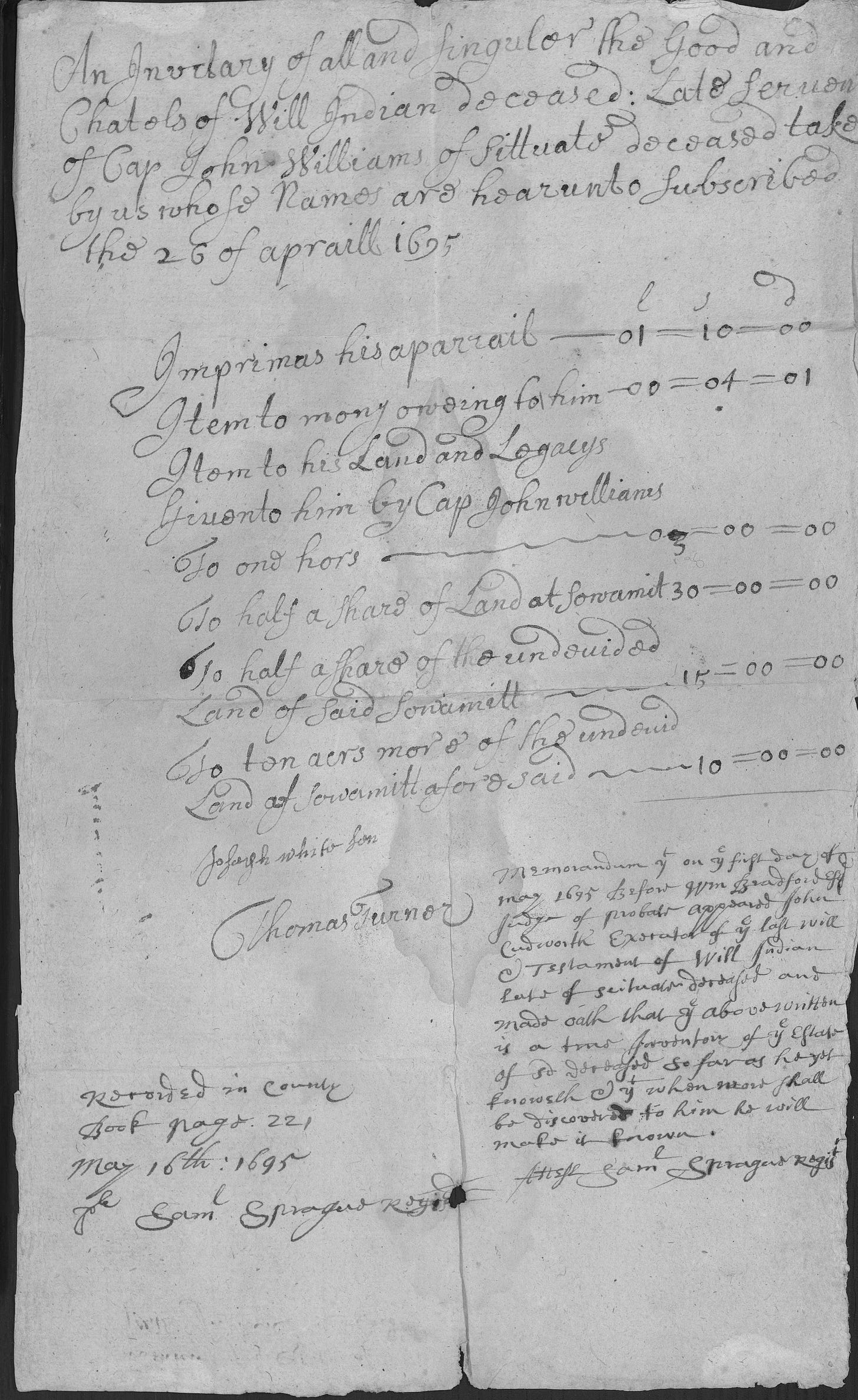

This 1695 probate file of “Will Indian” of Scituate, Massachusetts, is the earliest non-white person probate file I can locate in the old Plymouth Colony (Plymouth, Bristol, and Barnstable counties). It curiously notes that Will was the “late servant of Cap John Williams of [Scituate]” and that Williams gave Will some land.

The fact that Williams was a “Captain” and Will’s 1695 death occurred 20 years after King Philip’s War are clues worth investigating. What exactly was the relationship between Capt. Williams and Will?

Well, I can reveal that Captain Williams, who died a year before Will, will be featured in a future Open Notebook “Probate File of the Week,” and, spoiler alert, the relationship is probably what you think. If you haven’t yet subscribed, do so now so that you don’t miss the follow-up.

See earlier: Probate File of the Week: Francis Negro

Media Recommendation

Dr. Kellie Carter Jackson is a historian, Wellesley College professor, and a talented communicator of nuanced ideas. Dr. Jackson’s presentation on slavery in the Northeast dovetails nicely with other materials on slavery in New England. But it also connects local slavery to tangible conditions in today’s New England in ways that other works do not.

Essential Links

Boston Athenaeum, a remnant of the city’s Brahmin past, looks to engage an increasingly diverse population, The Boston Globe [Non-paywall via MSN]

The Forgotten Legacy of Boston’s Historic Black Graveyard, Dart Adams for Boston Magazine (From May)

City of Boston Archeology Finds Native Massachusett Pottery at Loring Greenough House, Facebook

The Myth of Native American Extinction Harms Everyone, The Boston Globe