Abigail Adams' enslaved Black "parent"

Did Phoebe model qualities recognized today as Abigail Adams' trademark feminism?

Hello, everyone. Substack tells me that this post is too long for email. You may need to finish this in your browser. Also, I’ve been in the news lately; catch up here and elsewhere. And don’t forget to share this with friends.

- Wayne

The Three Phebes

Introduction

John Quincy (1689-1767), for whom the city of Quincy is named, was an enslaver. In 1728, Phebe, an enslaved child, was born into John’s Braintree household; she went on to help raise Abigail Adams and was supported by Abigail and John Adams until she died in 1812. Archival evidence demonstrates that the baby Phebe who was baptized in John Quincy’s household in 1728, Phoebe Abdee of the Adams Papers, and Phebe Savil Oliphant of Quincy vital records are the same person.

Stunningly, Phoebe Abdee is indexed more than 70 times in the Adams Family Correspondence and she likely appears in more documents not currently online.

Woody Holton mentioned Phoebe several times in 2009’s Abigail Adams: A Life, and he published an essay about Abigail and Phoebe’s relationship in 2010. Yet, it’s conspicuous that sixteen years later more hasn’t been written about her; I can’t think of many Black Massachusetts residents of this era, free or enslaved, who appear in the archives seventy times. Perhaps Prince Hall does, but I’ve never counted.

The sheer number of archival appearances entice a fresh look at Phoebe, and details about her in the Adams correspondences beckon further. In 1787, Abigail wrote to her sister Mary Smith Cranch from London, noting, “I inclose a pamphlet upon darying which when you have read, be so good as to give to Pheby provided she becomes my dairy woman.”1 The casual instruction tells readers not only is Phoebe literate, but she was able to digest a technical manual and was expected to implement her newfound knowledge competently. Phoebe was educated and industrious.

In a 1798 letter, Mary wrote to Abigail in Philadelphia regarding a troubling incident in which a Black maid and her child were unjustly ejected from her white employer’s home on a snowy winter night, and who later arrived at Phoebe’s house on the Adams’ property. This arrival was not unusual as Abigail’s family routinely complained about Phoebe taking in Black lodgers. Mary continued, “this morning Phebe sent a Letter which she had written to mr Rawson for us to send.”2 So not only is Phoebe literate, she wrote letters. This suggests the possible existence of letters or other ephemera bearing Phoebe’s handwriting languishing in the archives. Notably, these holdings would not be attributed to or indexed as Phoebe Abdee, a name likely never used until the 1960s.

The letter further shows that Phoebe stood up for her community and resisted marginalization. Remarkably, much of what has been said about Abigail Adams can be said about Phoebe Abdee. This fact is revelatory when we recognize that Abigail loved and looked up to Phoebe, whom she once called her “parent.” Phoebe’s activism and the intelligence, literacy, competency, and independence revealed through letters prompt readers to wonder what kind of role model Phoebe was during Abigail’s childhood and young adulthood. Phoebe was undoubtedly an alternative model to the femininity displayed by Abigail’s affluent white mother, Elizabeth Quincy Smith. Also, it’s worth asking what Afro-indigenous traits and qualities Phoebe inherited from her mother and grandmothers, and are these traits recognizable in Abigail’s personality?

How much of Abigail Adams’ trademark feminism was modeled and nurtured by Phoebe? Future feminist historians and scholars of early Black American history will grapple with and identify Phoebe’s influence on Abigail. For now, I will leave you with a road map to Phoebe’s remarkable life.

Timeline

The name “Phoebe Abdee” has yet to reveal itself in the archives; it seems the editors of the original Adams Papers volumes published in the 1960s constructed this name. Despite this, I will refer to her as Phoebe Abdee for continuity and clarity.

1728 - Dutchess and Peter baptized their daughter Phebe and were listed as enslaved servants of John Quincy. I will refer to this Phebe as Phebe-1728 henceforth.

1740 - Elizabeth Quincy, daughter of John Quincy, married the Rev. William Smith of Weymouth; these are the parents of Abigail Adams. Does 12-year-old Phebe move with Elizabeth to the Smith household?

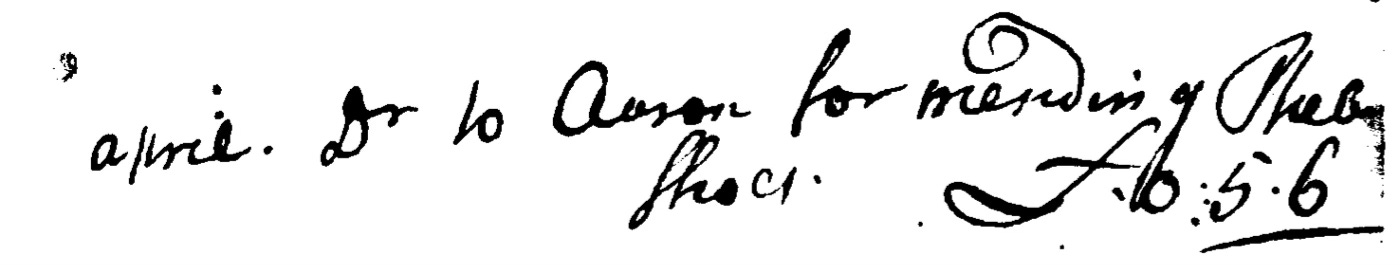

1749 – A log for Phebe’s shoe repair appears in the Rev. William Smith’s diary.

1777 - Phoebe Abdee (referred to as “Phebe”) enslaved by the Rev. William Smith, registered intention to marry Brester Sternzy in Weymouth (Phebe-1728 would be approximately 49 years old.)

1783 - Slavery is deemed incompatible with the Massachusetts Constitution.

1783 - September 17, the Rev. William Smith died. His will manumitted Phoebe. Subsequently, Phoebe moved to Abigail and John Adams' Braintree farm. In this probate file, an accounting of expenses for Smth’s estate also mentioned a person named Rose and an unnamed boy.

1784 - Phebe married Abdee (Abdi, Abda, Mr. Abdee, Abdy, indexed as William Abdee in the Adams Family Correspondence, although he is never referred to as William in the archives).

1792 - The northern section of Braintree, home of the Adamses and Phoebe, incorporated as the town of Quincy, named in honor of Phoebe’s first enslaver, John Quincy.

1798 - Abdee died on January 1.

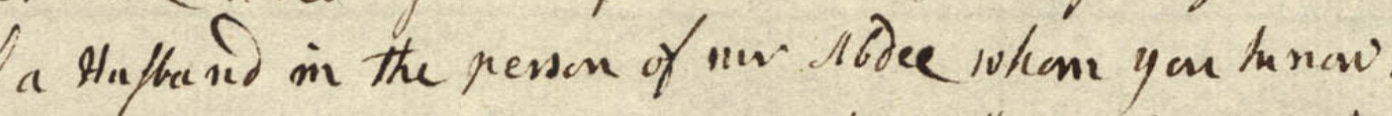

1798 - Abigail Adams lamented that Phoebe Abdee was “the only surviving parent I have.” This implies Phoebe Abdee is older than Abigail, who was 54 in 1798. Phebe-1728 would be about 70.

1799 - Phebe Savil marries William Olifant, September 19.

1799 - On October 17, John Adams mentioned Pheobe Abdee’s new husband, the earliest mention of this man. Adams also characterized Phoebe as an “old woman.”

1800 - Abigail Adams confirmed Phoebe Abdee’s new husband’s name is William.

1812 - Abigail Adams noted Phoebe Abdee being on her deathbed on September 12. She presumably died shortly after.

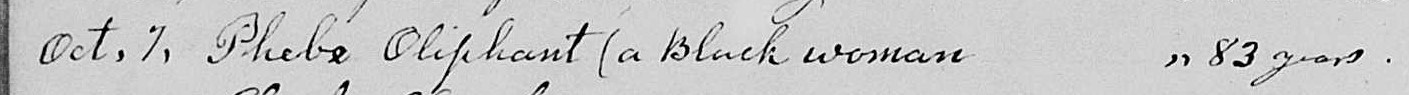

1812 - Phebe Savil Oliphant died on October 7 at age 83, putting her birth year as 1729.

Discussion

Phebe-1728 was baptized in 17283, likely as an infant. She was the daughter of Dutchess and Peter, and part of an Afro-indigenous nuclear family with five siblings. Elizabeth Quincy, daughter of Phebe’s enslaver John Quincy, married the Rev. William Smith of Weymouth in 1740.

Although no records exist of enslaved people leaving the John Quincy household for the William Smith household, it was common for white Massachusetts women to bring enslaved people from their fathers’ homes into the homes of their new husbands. Phebe’s age of twelve also falls within the range that historians like Jared Hardesty identify as ideal for acquiring servants or enslaved individuals.

Phoebe Abdee entered the Rev. William Smith’s house in 1749 or before; a 1749 entry in Smith’s diary records, "April. . .for mending Phebe shoes. . .£0-5-6."4

We know that Phoebe Abdee was older than Abigail Adams. In 1798, Abigail lamented that Phoebe was “the only surviving parent I have.”5 If Abigail was 54 at the time, prudent researchers must ask how much older Phoebe would have to be for Abigail to consider her a parent rather than a sibling. We know that Phebe-1728 was born sixteen years before Abigail, meaning Phebe-1728 would have been in her twenties during Abigail’s childhood and her early thirties in Abigail’s later teen years leading up to her 1764 marriage to John Adams.

Phoebe Abdee reclaimed her freedom via Reverend Smith’s 1783 will.6 In Cotton Tuft’s 1784 accounting of the Rev. William Smith’s estate, readers find a person named Rose and an unnamed “Boy.”7 Readers cannot glean further information on this pair; their races, ages, and relationship to the Smith household and each other are unknown. Expenses for shoes and britches for the boy appear on the same line as expenses for Phoebe Abdee.

Phebe-1728 would have been 56 years old in 1784. Phoebe Abdee was at least 40 years old in 1784 because that was Abigail Adams’ age in 1784. An age range of 46 to 56 opens the possibility of Phoebe Abdee having adult children and grandchildren. Unfortunately, descendants of Phoebe Abdee have not been found. Yet, researchers should remain receptive to the idea that Rose and the boy are Phoebe Abdee’s adult daughter and grandchild.

Furthermore, given that some interpretations of the Adams Papers treat Abdee as Phoebe’s “first husband” and William as her “second husband,” researchers should remain curious about Phoebe Abdee’s possible marriages or long-term romantic partnerships pre-1777. It strains credulity that Brester Sternzy8 was Phoebe Abdee’s first suitor when she was likely approaching age 50, and it’s possible that Phoebe married in her twenties and had a child or children.

While it’s difficult to reconcile Rose and the boy’s absence from Rev. Smith’s will, it’s easy to imagine that Rose labored, as an enslaved or free woman, in a different household and, in 1784, gained the freedom to spend time with Phoebe and visited the Smith household. Furthermore, it is inconvenient that Rose and the boy appear absent from the Adams Papers. Still, archival silences concerning Phoebe’s biological family should not negate the possibility that these are Phoebe Abdee’s blood relatives.

In 1784, Phoebe married “Abdi,” the man indexed as William Abdee in the Adams Family Correspondences (MHS’s Adams Papers Digital Edition). Undated manuscript extracts of Quincy's vital records use the Abdi spelling;9 the Weymouth town clerk’s records log him as “Abda.”10 Mrs. Adams first mentions him in 1784, noting in a letter to John that Phoebe married “Mr. Abdee whom you know.”11 But most curiously, the first time readers find the name William connected to Phoebe’s husband is in 1800, two years after Abdee’s death when Abigail identifies Phoebe’s new husband as William.12 Abdee is only called some variation of Abdee/Abdy/Abdi or simply Phoebe’s “husband” in original letters. He is never called William between his first mention in 1784 and after he died in 1798.

Furthermore, in 1754, “Abde Deacon Savil’s negro man,” married Esther, a woman enslaved by the Rev. Samuel Niles of Braintree, who officiated the ceremony and recorded it in his diary.13 The odds of two men in Braintree/Quincy being named Abdee are low, except for a father/son pairing. No birth record for anyone named Abde or similar spellings has been found in Braintree. Further, if Deacon Savil’s Abde married as a young twenty-something man in 1754, it would make him a perfect age range to marry a woman like Phoebe Abdee, who was likely in her fifties in 1784.

The absence of “William Abdee” from primary texts is significant because if Abdee never identified as William and no one ever called him by that name, it undercuts the notion that Abigail Adams’ companion Phebe was ever known as “Phoebe Abdee.” The earliest mention I can find of “Phoebe Abdee” is the first edition of the Adams Papers printed by Harvard University Press in 1963; the Massachusetts Historical Society transformed these volumes into the Adams Papers Digital Edition, now hosted on its website.

Knowing this, researchers can explain why “Phoebe Abdee” doesn’t appear in Quincy's vital records or genealogical databases. Furthermore, researchers should recognize that we don’t know which surname Phoebe Abdee chose to identify herself, which means endless possibilities exist.

However, a close parallel reading of the Adams Family Correspondence and Quincy’s vital records surfaces Phebe Savil,14 who married in 1799 and died as Phebe Oliphant in 1812.15 These years also correspond with Phoebe Abdee’s remarriage and death.

Abdee died January 1, 1798.16 Quincy’s vital records attest to William Olifant marrying Phebe Savil on September 19, 1799.17 On October 17, John Adams mentions “Phœbe’s Husband.”18 I’ve examined all Adams correspondence which indexes Phoebe between Abdee’s death and this October 1799 letter, and there is no mention of Phoebe’s husband. Secondly, in an 1800 letter, Abigail confirms that this man is named William.19

In Woody Holton’s 2009 book, Abigail Adams: A Life, he details a letter found in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s microfilm collection of unpublished Adams Family Papers. On September 12, 1812, Abigail writes that Phoebe is “sick and dying,” and Holton claims this was “the last reference to her in Abigail’s correspondence.”20 In Quincy’s vital records, readers find that on October 7, 1812, Phebe Oliphant, “a Black woman,” died at age 83.21

It’s remarkable that the Adamses comment on Phoebe Abdee’s remarriage and death within one month of Phebe Savil Oliphant’s marriage and death. It would be further remarkable if vital records detailed Phebe Savil Oliphant's marriage and death but ignored the Phoebe who lived and labored on the former President’s estate. Logically, these must be the same women. And the best explanation of how Phoebe entered William Smith’s home is that she was Peter and Dutchess’s daughter and moved with Elizabeth Quincy Smith at around age twelve.

Acknowledgements

Joseph Weisberg deserves special thanks for building the foundation of this project. I also thank Kate Gilbert for our productive conversations about Phoebe and for pointing me to additional material at Founders Online. And thank you to Michelle Marchetti Coughlin for the tip about Phoebe appearing in the Rev. William Smith’s diary.

Notes

Abigail Adams to Mary Smith Cranch, 8 October 1787. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 8. Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 186.

Mary Smith Cranch to Abigail Adams, 23 February 1798. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 12. Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 415.

Phebe. Church records, 1688-1848 [Quincy, Massachusetts]. FamilySearch.org (Affiliate Library wall). p. 76, image 82.

“William Smith Diary.” 1749. William Smith diaries, 1728-1778. Massachusetts Historical Society. ProQuest History Vault: Revolutionary War and Early America. April.

Abigail Adams to John Adams, 11 February 1784. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 13. Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 289.

William Smith. 1783. Suffolk County Probate File Papers # 18039. AmericanAncestors.org, image 7.

Brester Sternzy and Phebe registered marriage intentions in 1777. Records of births, marriages and deaths, 1655-1805. Weymouth, Mass. Familysearch.org. p 93, image 56.

Abdi and Phebe. Church records, 1688-1848 [Quincy, Massachusetts]. FamilySearch.org (Affiliate Library wall). p. 17, image 51.

Abda and Phebe. Records of births, marriages and deaths, 1655-1805. Weymouth, Mass. Familysearch.org p. 173, image 106.

Letter from Abigail Adams to John Adams, 11 February 1784 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Abigail Adams to Cotton Tufts, 15 March 1800. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 14, Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 174.

Samuel Niles journal, 1697-1777, in the Braintree, Mass. First Congregational Church records, 1697-1871, RG5302, The Congregational Library & Archives, Boston, MA. 241.

William Olifant and Phebe Savil. Town and vital records, 1792-1890 [Quincy, Massachusetts]. Intentions of marriage, 1792-1850. FamilySearch.org. p. 8, image 10.

Phebe, Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. Vol, 1, Deaths, Quincy, Norfolk County, Massachusetts. Ancestry.com. p. 23. image 693.

Mary Smith Cranch to Abigail Adams, 7 January 1798. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 12, Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 350.

William Olifant and Phebe Savil. Town and vital records, 1792-1890 [Quincy, Massachusetts]. Marriages, births, 1792-1844. FamilySearch.org.

John Adams to Thomas Boylston Adams, 17 October 1799. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 14, Digital Edition. Massachusetts Historical Society. 16.

Abigail Adams to Cotton Tufts, 15 March 1800. Adams Family Correspondence, volume 14, Digital Edition. 174.

Woody Holton. 2009. “Abigail Adams: A Life.” Kindle Edition. 381, citing Abigail Adams to Elizabeth Smith Shaw Peabody, 11 September 1812. Microfilms of the Adams Papers Owned by the Adams Manuscript Trust and Deposited in the Massachusetts Historical Society, roll 414. Phoebe appears twice more in Abigail’s correspondence in letters to Ann Harrod Adams dated 13 September 1812 and 20 September 1812.

Phebe Oliphant. Church records, 1688-1848 [Quincy, Massachusetts]. FamilySearch.org (Affiliate Library wall). p. 201.

Nice detective work!

Wonderful puzzle piecing! thanks for this insight--