A Conversation with Kyera Singleton

The Royall House director on asking new questions and history as a liberation project.

The humanities are alive and well because humans are relentless truth seekers. We question what we hear and we create ways to understand our world.

The public humanities depend on humans who call our attention to the previously unknown or unseen, to the truths that lie hidden inside archives. We need institutions willing to excavate the truths that were buried by the misinterpretations or neglect of previous generations.

In an earlier era, the historic marker sought to consolidate a history and give a space meaning. Without them, we might walk past the building or across the field and miss out on its role in the lives of our ancestors.

I am a voracious consumer of these markers. The smallest plaque on a brownstone, a weathered square of text attached to a wood post near an old battlefield, the bronzed dedication of a minor monument—these things stop me in my tracks. I am attracted by what is there, and what isn’t. Why is this spot proclaimed important? How do the markers reveal their origins? Who paid for this description and what was their agenda? Is a rewrite in order?

An example: A historic marker stands just inside the fence that surrounds the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Mass. It reads:

Mansion built by Isaac Royall who came here from Antigua with his slaves in 1732. His son, Isaac Royall, a loyalist, founded at Harvard the oldest law professorship in the United States. Headquarters of General John Stark during the Siege of Boston.

The sign was the work of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentieary Commission, which celebrated the colony’s 300th anniversary in 1930 by erecting markers that you still spot around the Commonwealth. The landmarks remain useful: they reflect the worldviews of the people in charge of public history a century ago. They deserve your attention because they are so very incomplete.

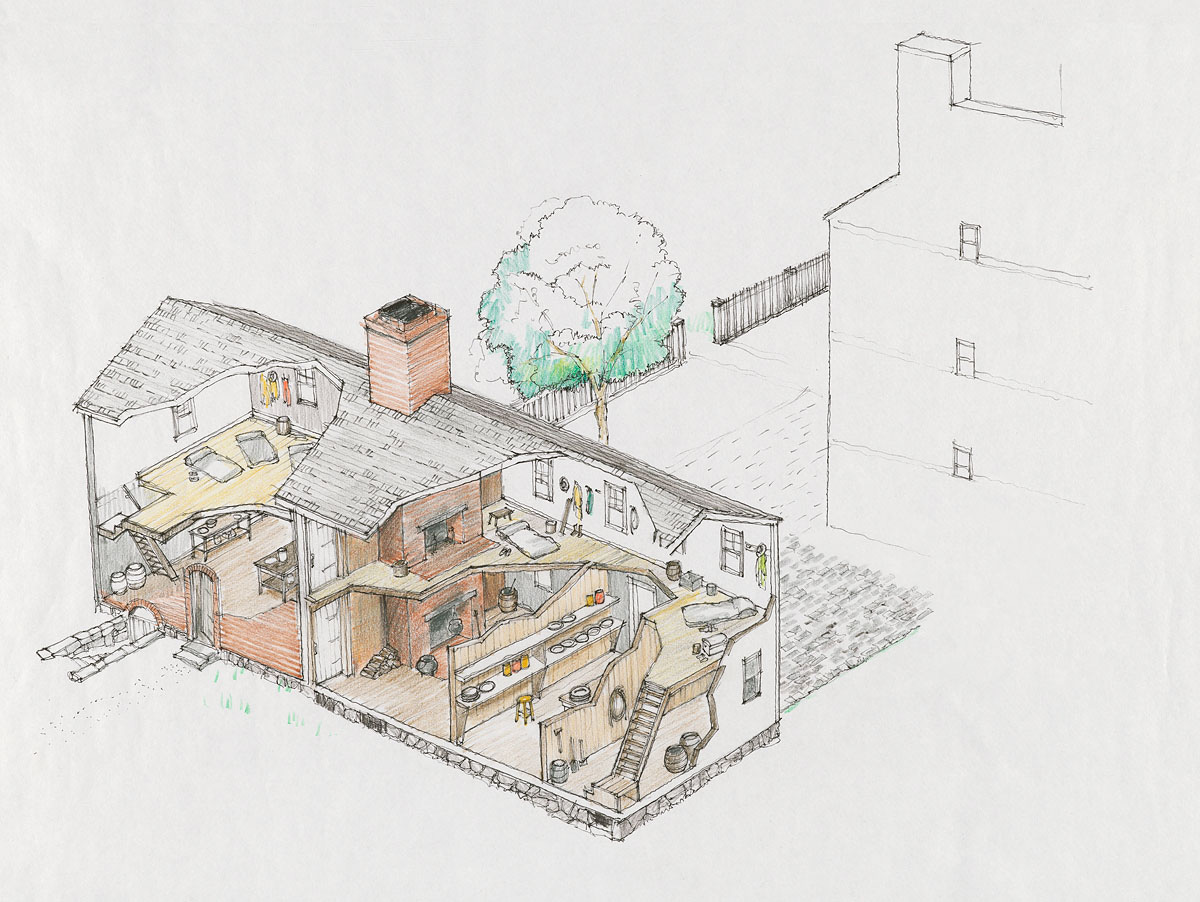

The story of Isaac Royall and this corner of Massachusetts is so much more complicated and provocative. You can read more about Royall House and Slave Quarters here. Per their website, the property includes the “only known extant separate slave quarters in the northern United States.” The story of these buildings and the people who lived here is vital to our understanding of the past and pressingly relevant to our present.

Fortunately, this marker is not the last chapter in that story. Today, Royall House is a must-visit location for anyone seeking to understand the history of Northern slavery. It is a vibrant humanities space led by Kyera Singleton, a scholar dedicated to turning the gaps in the record into sparks of repair and equality.

I’ve been fortunate to get to know Singleton over the last three years. Her human-centered approach to the archives makes a tour of the museum into a reckoning. Each time we talk or I get to visit Royall House, Singleton’s vision seems to grow clearer, buoyed by new discoveries and insights.

We talked via email this time. Below is an edited version of the conversation.

When did you start as Executive Director at Royall House?

I, officially, started on April 1, 2020. I actually accepted the position the day before the country shut down, during the first month of the pandemic. What a time to start a new position! It’s been a whirlwind but in the best ways possible. We have navigated the ongoing pandemic successfully and have grown in new and exciting ways.

You and your team continue to unearth new facts and connections from the archives. What do we know today about life at Royall House that we didn’t know five years ago?

The archive represents both a site of discovery and frustration when conducting research on the lives of enslaved people. Oftentimes, we are looking through box after box in the hopes of finding a document, a name, or any piece of evidence that helps us understand, and ultimately, memorialize the Black women, men, and children who were enslaved by the Royalls.

By asking new questions of the same archives, we’ve been able to unearth a lot of new information. For example, a fellow researcher sent us a document about Plato, a man who was enslaved on the Royall Plantation and who is listed as dying in 1768 in the Medford Vital Records. However, we now know much more about Plato’s death after looking into the judicial records. Plato actually drowned on June 8th, 1768, while washing a horse in the Mystic River in Medford. This information gives us new insight into the type of labor performed by Plato and the circumstances of his death. We are able to think more fully about sites around Medford in which enslaved people would have been compelled to perform labor at, and how they would have come into contact with other enslaved and free Black people at times as well.

However, the archive is still a site of frustration for me because the new information we learn does not necessarily give us more insight into Plato himself so we also have to contend with the silences of the archives. To be clear, my frustration with the archive just presents us with an amazing opportunity to bring in literature, art, archaeological evidence, and other primary and secondary source materials to expand and build the world of the enslaved people on the Royall Plantation.

Thanks to a generous grant from Mass Humanities, we are learning new information about Belinda Sutton and her family members. I am so excited to present that information later this year!

Relatedly, what are you hoping to learn and connect over the next year?

There is still so much that we do not know about the Black women, men, and children enslaved by the Royalls and not only in Medford (also what were then Freetown and Stoughton, Massachusetts), but also in Rhode Island, Antigua, and Surinam. I get excited just thinking about all of the different possibilities that can come out of doing this research.

Over the next year, I am really hoping to learn more about the enslaved people who were left behind after Isaac Royall Jr. left Massachusetts during the Revolutionary War.

Can you talk about the Royall’s ties to the Caribbean and the ways that allows us to see this larger global system of enslavement?

Isaac Royall Sr., who grew up in Dorchester, actually established and ran a sugar cane plantation in Antigua, which is how he built the Royall family’s wealth. In addition to enslaving and trading Black women, men, and children, he was also involved in the business of slavery through trading in goods such as sugar and rum.

You consulted on the new exhibit at the MFA on the Edgefield potters. Where do you see their work in the longer story of enslavement and resistance?

I did! It’s such an amazing show and the entire team at the MFA really is spectacular and handled the stories of the potters with such care. It was an honor to contribute to the exhibit.

I’m going to answer this question in two ways.

When it comes to the history of decorative arts in this country, we do not often think about how essential enslaved labor was to shaping and making the goods of everyday life in places like Edgefield and Boston. These vessels, which are heralded as important pieces of art today, were made by Black potters. And while these potters were compelled to do this labor, we know that these Black potters made these vessels their own by inscribing poetry, dates, their names, and playing with the shape and size of these sacred objects. In thinking about resistance, we see that potters like Dave, who signs his pots, quite literally etches himself into history. He not only refuses to be forgotten, he also forces us to bear witness to his craft and survival through the art he created that is now on view at the MFA.

As a historian, I am always thinking about local histories so I just knew I had to talk about Jack and Acton, who were two enslaved potters in Charlestown, which is now a neighborhood in Boston. For me, it was important that people know that the story of enslaved potters was not just a southern story. The team at the MFA agreed and they allowed me to write about Jack and Acton, which I did by building on research by Boston archaeologist Joe Bagley and historian Jared Hardesty, who told me about the potters.

However, it wasn’t enough to just say there were enslaved potters in Boston, too. I never want to reduce enslaved people to their production. So I was able to do my own research and I uncovered that in 1742 Jack married Flora, a woman enslaved by Joseph Gowen. It is essential that we always remember that enslaved people built lives for themselves and that we have a responsibility to do the work to learn about them beyond the goods they produced!

We’ve talked about the demands on your schedule in a time when so many institutions—museums, funders, academia—are looking for guidance as they come to terms with the legacy of slavery. How are you choosing the spaces and partnerships you contribute to?

This is a great question and a really hard one to answer.

I am extremely humbled that I get to do what I love every single day. And because I am passionate about the history of slavery, I want to do everything and I want to partner with everyone. I am fortunate enough to have colleagues who see me and call my name in rooms even when I am not there.

However, I am still learning how to balance all of the different demands on my schedule, and it’s been a steep learning curve, if I am being honest.

First and foremost, I believe history is a major vehicle through which we can understand and affect the conditions of the present in order to build a better future. For that reason, I am invested in spaces and partnerships that are aligned with my mission to talk about how the legacies of slavery impact Black and Brown communities every single day in this country. I often choose spaces and partnerships that are community centered and deeply care about making the work on slavery accessible. I see the work that I do as part of a liberation project. I hope that work and the life I lead helps us all get a little bit closer to freedom every single day.

You have a compelling vision for Royall House evolving into a national center for the study of Northern Slavery. First, am I describing that correctly and are you willing to share that?

I am biased, of course, but the Royall House and Slave Quarters is in a unique position in Massachusetts to tell a local, national, and global history of enslavement and Black resistance. Thus, my vision, and my plan, is to make the Royall House and Slave Quarters the center of the study of Northern Slavery, and a place where people can come to reckon with the past and the right now.

From my perspective, this would be transformative for Boston and for the country, both for the way we see the past, but also to amplify the accountability we feel towards repair and justice. More Americans should feel a part of this story–and the way we move closer to freedom.

How can people help you make this vision a reality?

People can help in a myriad of ways–both big and small. I’ll share one of each.

One of our organization’s main goals is to restore the Slave Quarters back to what it would have looked like in the 18th century before it was renovated by the Daughters of the American Revolution. This is a large project but an extremely important one.

The other way people can help is to get involved with the museum, and to talk about the work we are doing. Come visit the site to see how transformative it is, become a volunteer, become a member, join us for a public program, and bring your family and friends on a tour. The history of slavery is not just Black history, it is American history. More importantly, we are all stakeholders in raising the visibility of slavery and Black freedom movements in Massachusetts.

Last question: Why do we need the humanities?

The humanities are essential to how we understand society through the cultural texts people create. Where would we be without the people who document and tell their own stories and the histories of others—especially those of marginalized communities?

Click here to support Royall House.

Read more:

National Humanities Alliance: “Interview with Kyera Singleton”

WBUR: “Pottery exhibit at the MFA spins a tale of artistry despite the odds”

Apply:

Royall House received a 2021 Mass Humanities Expand Mass Stories grant. The deadline to apply for 2023 grants is May 20. More here.

Watch: My conversation with Kyera Singleton back in October 2020: