Thank you for reading Open Notebook! This edition examines five women who should be household names when discussing the history of slavery in Massachusetts. For some readers, these names are intimately familiar. To readers who are newly exploring the subject through my work, this may be their first exposure to these women. Either way, I hope I packed in some new details for everyone. - Wayne

Elizabeth Freeman

Elizabeth Freeman is remembered as the first1 enslaved African-descended woman to file and win a freedom suit. However, did you know that the original court transcript for that case, Brom and Bett v. Ashley, is available on FamilySearch?

Freeman was born enslaved in New York, and in the 1770s, she lived in the household of Colonel John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts. After enduring physical abuse from Ashley's wife, Freeman fled and refused to return to the Ashley household.

She sought and found an ally in attorney Theodore Sedgwick.2 Freeman overheard white men discussing freedom from tyranny and “enslavement” from England and applied the concept to her court case. In 1781, with Theodore Sedgwick's help, Freeman initiated Brom and Bett v. Ashley, winning and setting a solid precedent for abolition in Massachusetts. Notably, this case was adjudicated less than a year after ratifying the state’s constitution and did not depend on a statutory violation by enslaver John Ashley.

After gaining her freedom, Freeman worked as domestic help in the Sedgwick household, helping with child care. Freeman and her sister later bought property in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and passed away on December 28, 1829, at 85 and is buried in the Sedgwick family plot.

For context explaining how important Elizabeth Freeman is to our region and nation’s history, watch this lively and provocative panel discussion from WGBH’s Basic Black, or listen to it as a podcast.

Host Callie Crossley will be joined by: L’Merchie Frazier, a Visual Activist and Director of Education for the Museum of African American History in Boston and Nantucket; Sophia Hall, Deputy Litigation Director for Lawyers for Civil Rights in Boston; and Kyera Singleton, Executive Director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford.

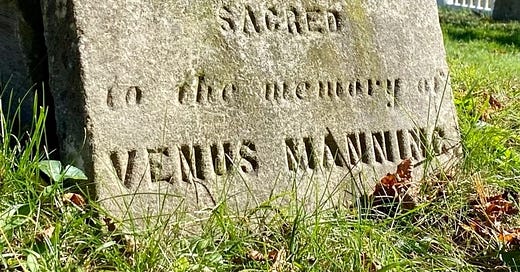

Were Venus Manning & Maria Stewart friends?

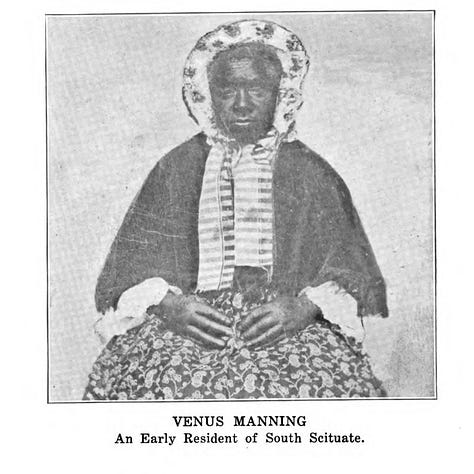

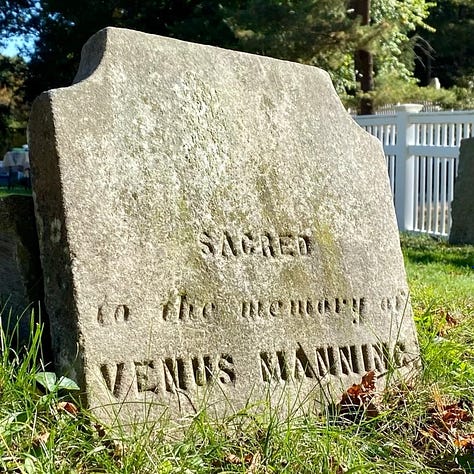

I frequently mention Venus Manning, partly because she lived a remarkable life and partly because there is a large hunk of that life—a 35-year stint in Boston and Roxbury—with very few data points. And I want to widen my search net through my readers.

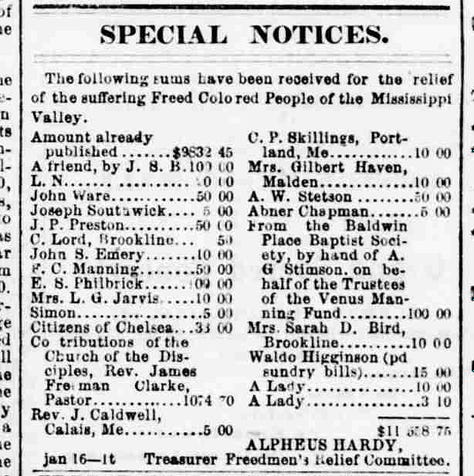

Venus, who you may remember from the February 15 edition of Open Notebook, was born in 1777 enslaved, the fifth child of a couple enslaved by a shipbuilder working in Hanover/Scituate, Massachusetts, along the North River. She relocated to Boston, and at age 28 she chose to be baptized at the Baldwin Place Baptist Church. In the ensuing years, Venus married Thomas Manning, gained financial literacy, became a life member of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, and donated to Baptist foreign missions.

One detail I’ve never shared is that 1820 census records show a Thomas Manning and a woman of a similar age living on Belknap Street (today’s Joy Street on Beacon Hill.) Both were enumerated as “Free Colored Persons.” Later records hint that the Mannings may have lived in the North End close to the docks. Manning returned to what is today Norwell, a widow sometime between 1841 and 1850.

Beacon Hill was the center of nineteenth-century Black Boston,3 ground zero for Black activism, a vital hub of the Underground Railroad, and home to important historical Black figures such as Harriet and Lewis Hayden, William Cooper Nell, Primus Hall, and numerous others.

Steps from the Manning household was an important building that still stands: the African Meetinghouse. Venus Manning was baptized at Baldwin Place the same year this church was established in 1805, and the structure was built a year later. Today the church houses the Museum of African American History and is the oldest standing Black church building in the U.S.

Back then, beyond serving its Black neighbors' spiritual lives, the Meetinghouse hosted educational programs for children and adults as well as conferences and speeches for various abolitionist groups and speakers. Although she worshipped elsewhere, I cannot imagine a scenario where Manning, a life member of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society who once lived within shouting distance of the Meetinghouse, was not tuned into its abolitionist programming.

One speaker who appeared at the Meeting House was Maria Stewart. Stewart was a pioneering abolitionist, lecturer, and writer who significantly impacted the Boston anti-slavery scene. And, like fellow Black abolitionists Manning and David Walker, the inspirational radical by whom Stewart was heavily influenced, Stewart was once a Belknap Street resident.

Born in Hartford in 1803, Stewart grew up orphaned and indentured. She moved to Boston in 1826 and worked as a domestic servant. During this time, she became involved in the abolitionist movement and delivered powerful speeches supporting abolition and women's rights.

Stewart was amongst the first women of any race to speak out publicly, much less against slavery, and advocate for the full citizenship and rights of African Americans and women. Stewart fearlessly challenged racial and gender conventions and delivered her speeches with conviction and zeal.

One of Stewart's most famous speeches was delivered on September 21, 1832, at Franklin Hall in Boston. The speech, titled "Why Sit Ye Here and Die?" was a call to action for African Americans to resist oppression and work toward their liberation. In the speech, Stewart urged black men and women to take up the cause of abolition and to fight for their rights as full citizens of the United States. She also criticized black men who refused to support the cause of women's rights, arguing that true liberation required the full participation and equality of all people.

I am also one of the wretched and miserable daughters of the descendants of fallen Africa. But, do you ask, why are you wretched and miserable? But, I reply, look at many of the most worthy and interesting of us doomed to spend our lives in gentlemen’s kitchens. Look at our smart, active and energetic young men with souls filled with ambitious fire; if they look forward, alas! what are their prospects? - Maria Stewart, "Why Sit Ye Here and Die?"

Stewart left Boston in 1834, and in addition to her brief influential career as a public speaker, Stewart continued to work for social justice in other ways. She wrote articles for abolitionist newspapers, taught school, and helped to found the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society, an organization dedicated to promoting education and self-improvement among black women.

Maria Stewart's speeches and writings challenged her time's prevailing attitudes and helped pave the way for future activists and reformers. And knowing Stewart’s story allows us to imagine a rich and active life for Venus Manning’s lost years; there were possibilities for Black women to contribute to and support abolitionist causes beyond passively sitting in segregated pews listening to white clergy give anti-slavery sermons.

I recommend looking into Stewart further. Start with Clint Smith’s insightful treatment of Maria’s life for Crash Curse and then read Maria’s speeches; they’re brief, concise, and (mostly) on point.

Belinda Sutton

Belinda Sutton was an enslaved woman who lived in Medford, Massachusetts, in the 18th century. She was born in Ghana and brought to America as a child. Sutton was enslaved by the notorious Royall family and was abandoned when enslaver Isaac Royall, Jr., and his family fled Massachusetts during the Seige of Boston.

Eight years later, in 1783, Sutton petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for a pension from Royall’s estate. She won but received only two payments, so she had to petition the General Court five more times. She never got paid, but Harvard sure did.

There’s more to the story, and the best place to learn more about Belinda Sutton’s historic activism is the museum at her former home, the Royall House and Slave Quarters. Also, to support another independent creative, I’ve linked to Jazz’s Black Gems Unearthed episode filmed in front of the Royall House when it was closed for COVID.

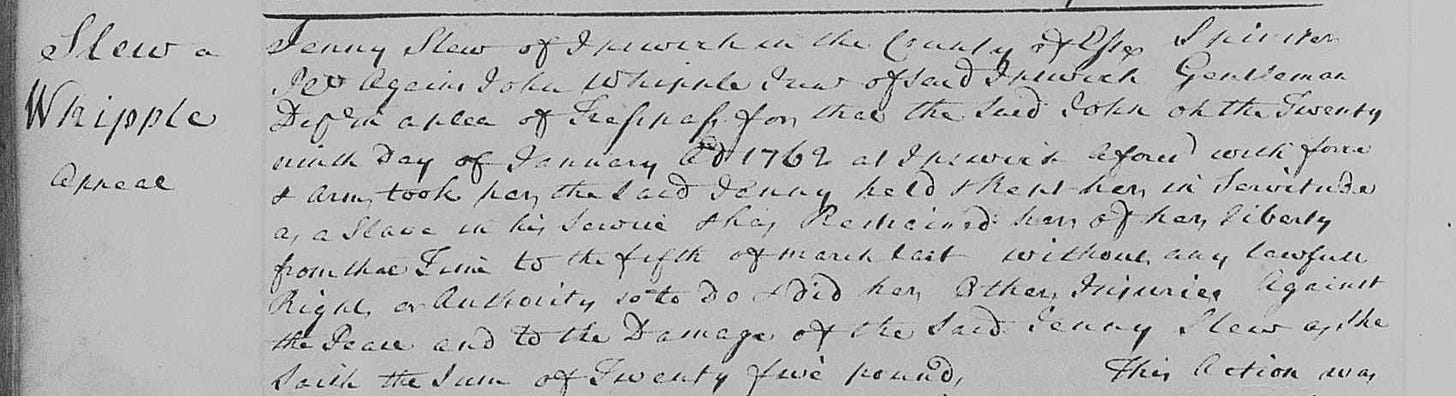

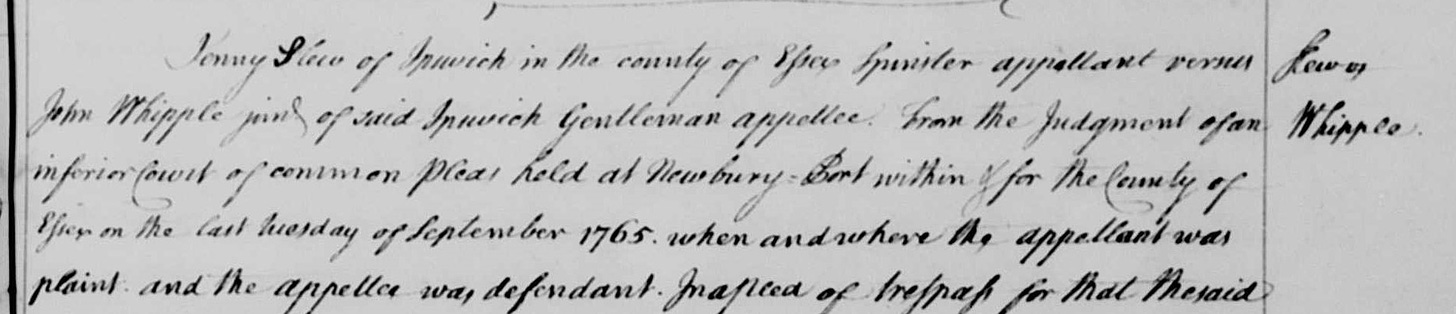

Jenny Slew

Jenny Slew was born in 1719 to a white free woman and an enslaved Black man. She lived freely until John Whipple4 pressed her into slavery illegally in 1762. Slew took legal action and sued Whipple for holding her in bondage, asserting that since her mother was free, she was free too. Whipple argued that he had a bill of sale for her purchase and that, as a married woman, she had no legal standing to sue him. Her petition was dismissed, but Slew appealed and won the case in 1766. The court ruled that Slew was a "spinster" and ordered Whipple to free her, awarding her £4 in damages and £5 in costs. Slew's lawyer, Benjamin Kent,5 successfully argued the case by pointing out Whipple's failure to produce a bill of sale.

I invite you to read Gordon Harris’s compelling work at Historic Ipswich, Freedom for Jenny Slew. It’s a great story with some excellent genealogical and biographical work, and Harris ties Jenny Slew to Abigail Adams.

Although Elizabeth Freeman was the first woman born into slavery to win her freedom via the Massachusetts courts, Mariah, a once enslaved woman, won her daughter’s liberty through a 1717 Scituate, Mass., court case. See also the Jenny Slew case above. These facts do not undermine Freeman’s brilliance or importance but add texture and context.

Theodore Sedgwick is notable as a member of the United States Congress and a slaveholder.

Here’s a virtual tour of the Black Heritage Trail of Beacon Hill from the National Parks Service. Click here for my Early Black Heritage Trail for Hanover, Norwell, and Scituate.

The Whipple name is inseparable from the region’s history of slavery. In addition to the five Ipswich Whipple enslavers mentioned in Harris’s article, the family’s New Hampshire cousins were also slavery enthusiasts. For example, Joseph Whipple tried to return Ona Judge to George and Martha Washington after the enslaved woman escaped the presidential residence in Philadelphia for Portsmouth, New Hampshire. (Listen to this excellent podcast episode!) And enslaver Gen. William Whipple was a signer of the Declaration of Independence for New Hampshire; he enslaved Pvt. Prince Whipple and his brother Cuffee.

For more on slaveholding attorney Benjamin Kent, see Open Notebook for November 7, 2022.

So many comma splices. 🤦♂️ And because this is a newsletter, my errors are preserved for ever.