Slavery, Shipbuilding, and the South Shore

Slavery & Shipbuilding on the South Shore of Massachusetts, Edward Wanton & Intergenerational Slavery in Rhode Island, Phillis Wheatley & her Husband John Peters

Welcome! Will you take a moment to forward this email or share a link to this newsletter with other historians and genealogists? If you’re new, check out past editions and visit eleven-names.com for more. - Wayne

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. Andrew Peters

This Middleton, Massachusetts, minister held an unnamed enslaved man and a woman at his 1756 death. Vital records show that this is the minister who baptized John Peters, the future husband of Phillis Wheatley, in 1751.

For John Peters’ baptismal record, see Vital Records of Middleton, to the end of 1849. Cornelia Dayton’s scholarship on Phillis Wheatley Peters’ “lost years” points us to a 1780 deposition that states John Peters spent his early years with John and Naomi Wilkins before he was sold as an adolescent. Her work confirms that Peters was baptized as “Peter” and for some years identified as Peter Francis, then Peter Frizer.

Shipbuilding & Slavery on the South Shore

I’m creating a presentation for a local conservation group about slavery and the South Shore. In the spirit of keeping an “open notebook,” I want to share some resources regarding the South Shore shipbuilding industry’s connection to slavery.

First is this instructive passage from Dr. Eric Kimball’s unpublished dissertation housed at the University of Pittsburg. It notes that the South Shore received an economic boost in 1753 due to the slave trade:

Boston port records for 1753 reveal a brief shipbuilding boom in that year especially as the West Indian markets continued to expand and merchants needed more ships to bring provisions to sustain the plantation complex. Yet most vessels were not built in Boston. Of the 444 ships built in 1753, 378 hailed from shipyards in Massachusetts and totaled 22,251 registered tons. This represented over 88% of all registered tonnage. Boston-built ships constituted 71 of these 378, totaling 6,643 tons and accounting for over 29% of all Massachusetts’ built tonnage. The largest number of ships, 118 in all and constituting 5,184 registered tons or over 23% of all Massachusetts’ built ships, were from shipyards in the Plymouth region: Hingham, Hull, Scituate, Hanover, Bridgewater, Pembroke, Marshfield, Duxbury, Kingston, and Plymouth. . .Overall, about 70% of the ships listed in the port records for 1753 that were built in Massachusetts originated in ports outside the Boston area.

[ref: Kimball, Eric (2009) An Essential Link in a Vast Chain: New England and the West Indies, 1700-1775. [341-342] Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. (Unpublished)]

Furthermore, I used SlaveVoyages.org to examine what role the South Shore’s shipbuilding industry played in the context of the whole state. Here’s a spreadsheet that includes every Massachusetts “slave ship” building port. The ships, by and large, were not built explicitly or exclusively as stereotypical “slave ships,” rather these were ships built to service commerce in the New England region and the greater Atlantic World; enslaved humans were just one type of cargo along with sugar, molasses, salt, timber, and livestock that composed the triangular slave trade.

The four tabs in this workbook show, among other things, that the South Shore accounted for 9% of Massachusetts vessels that transported enslaved individuals and 7% of the slave voyages made by Massachusetts-built ships.

Next, zooming in, we can consult L. Vernon Briggs’ History of Shipbuilding on North River. Although this 1889 book does not chronicle enslaved and free Black life on North River as much as one might hope, sharp readers will find value. Surveying ownership of North River vessels, we learn that several ships were purchased and operated by Caribbean planters, including eight ships registered in Barbados and a 25-ton sloop called “Mayflower” built in Scituate in 1706 and purchased by Joseph and Isaac “Ryal” of Antigua. This, of course, is Maine-born and Dorchester-bred Isaac Royal, Sr., of the Royall House and Slave Quarters, in Medford, Massachusetts.

To learn more, visit the North River Early Black Heritage Trail, a virtual tour/story map I built earlier this year.

Sidebar: Edward Wanton

England-born Edward Wanton was a Boston Congregationalist who, as tradition goes, assisted in the execution of the Boston Martyrs—Quakers that Puritans executed for practicing their faith. Disturbed by the injustice, Wanton adopted Quakerism and faced persecution, even after moving to 80 acres in Scituate, Massachusetts. He was a sucseful religious teacher and established a shipbuilding business, the location of which is in today’s Norwell that you can visit it if you paddle the North River.

The Wanton name is prominent in New England slavery, and it begins with Edward. Below we see a 1712 ad where the Quaker ship carpenter is seeking Daniel, a 19-year-old man, tall, with “thick curl’d Hair with a bush behind, if not lately cut off.”

In 1714, Daniel is still Wanton’s property, but he has been hired out to his son-in-law, John Scott of Newport. Note that Daniel is a skilled tradesman and is described as a “Ship Carpenter.”

Wanton’s sons removed to friendlier religious climes in Rhode Island. Two of Wanton’s sons and two grandsons became governors of the wealthy slave-trading hub. Not only did Edward Wanton’s descendants continue his Quakerism and slaveholding traditions through generations, but they also profited greatly from the slave trade.

As a testament to the obscene wealth made by the Wantons and other slave traders, Joseph Wanton (d. 1780) is shown at the center of Sea Captains Carousing in Surinam, a 1754 John Greenwood painting likely commissioned by Capt. John Jenkes. The painting depicts a decadent scene of Rhode Island merchants playing cards, smoking pipes, reveling and over-imbibing. There are also four enslaved near-nude figures—two women serving the captains and two people, perhaps children, asleep in the bottom left corner. Wanton, too, is passed out. He is the man in the blue coat having a bowl of liquid poured over him and, fittingly, is being vomited on.

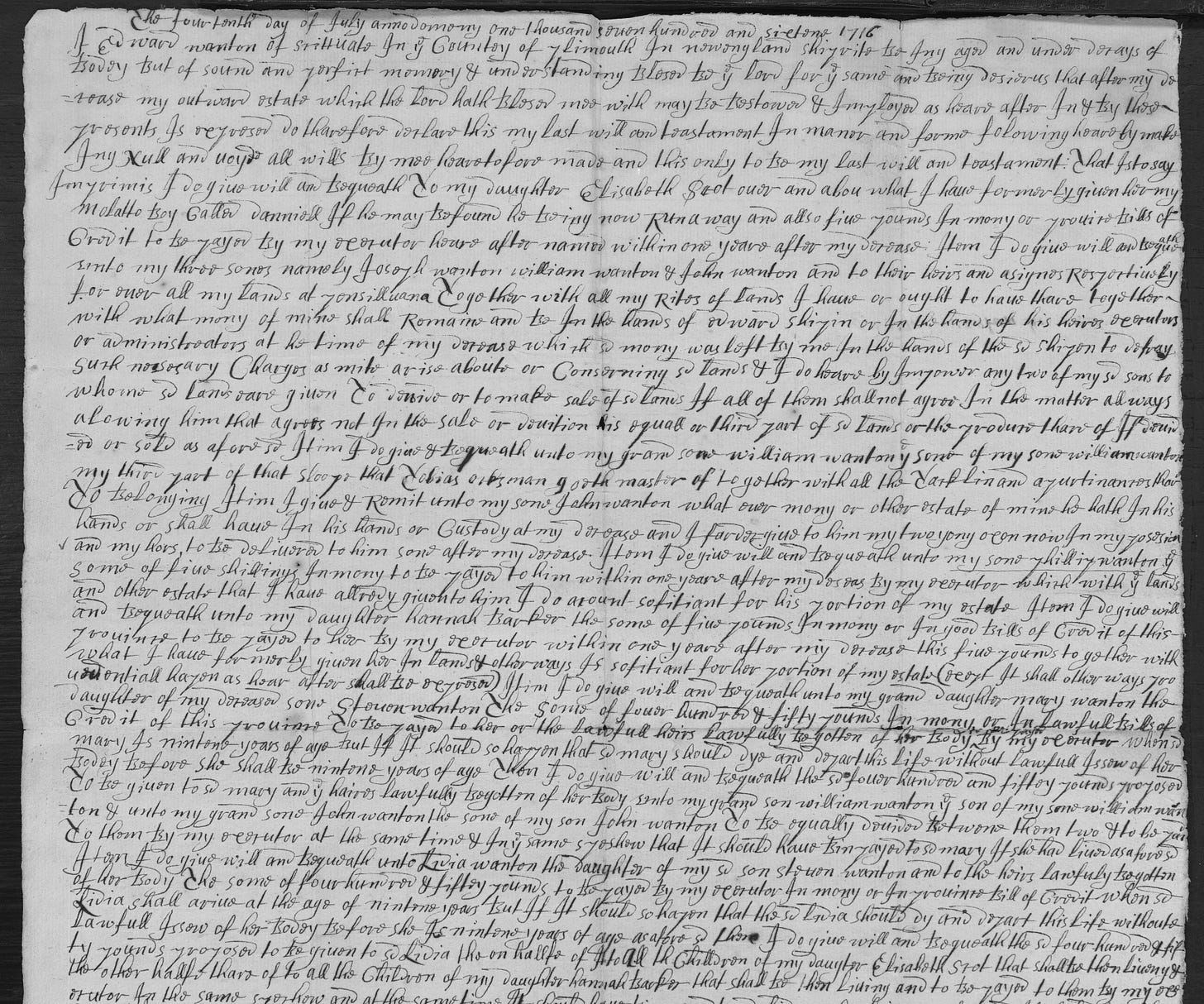

Probate File of the Week: Edward Wanton (1716)

To daughter Elizabeth Scot, over and above what I have formerly given her, a mulatto boy called Daniel, if he be found, he being now run away.

1716: Daniel is yet again, or perhaps still, seeking freedom. For a deep dive into Edward Wanton and his descendants, read this entry in the genealogical blog Miner Descent.

From Plymouth County Court Records: Sarah Curtice and Jo

Corporal punishment was widespread in Plymouth County, especially for men and women who conducted sexual relationships across racial lines. Fornication had long been punishable by whipping, but many cases were disposed of through the collection fines. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, when white couples could mitigate punishment by getting married, mixed-race couples disproportionally faced a sentence of whipping. Especially vulnerable were Black men who did not earn an income and therefore could not pay the cash fine. The 1698 case of Jo and Sarah Curtice is one example.

Jo a Negro servant. . .is sentenced to be publickly whipt ten stripes which was accordingly inflicted on him.

Transcript:

Sep 22 1698. . .

That Jo a Negro servant to William Holbroke of Scituate convict of committing fornication with Sarach Curtice of Scituate as up on oath she affirmed is sentenced to be publickly whipt ten stripes which was accordingly inflicted on him.

The above sd Sarah Curtice convict as abovesaid by her own confession sentenced to pay a fine of fifty shillings or be publicly whipt ten stripes who paid said fine to [the] sheriff…2-10-0

Sarah Curtice above named made oath in court [the] day about to that Jo negro and no other person is the real father of [the] bastard child lately born of her body & that he begot the same upon her. And she also confessed hath provided fifty shillings of him since [the] birth of sd child.

Media Recommendation: “Recovering the Lost Years of John Peters and Phillis Wheatley Peters”

In 1780, John and Phillis Wheatley Peters returned to John’s childhood hometown of Middleton, Massachusetts, where he was conditionally deeded a 110-acre farm by his former enslaver. Watch professors Cornelia Dayton and Henry Louis Gates discuss the conditions that brought Phillis and John Peters to Middleton in this virtual presentation to the American Antiquarian Society.

Essential Links

Photo Essay: the Pokanoket Wampanoag at the John Alden House,

for theDick Morey “in the Capacity of a Servant” and Seeking John Morey in Roxbury by J. L. Bell at Boston 1775.

Considering History: Wamsutta James, Thanksgiving, and the National Day of Mourning,

for The Saturday Evening PostUntold stories of the past: Historic Northampton examines city’s legacy of slavery, The Daily Hampshire Gazette and the Results Of Historic Northampton's Slavery Research Project