Welcome, readers. This week we consider “Black Loyalists,” the first printing press in Africa, fire and animal abuse as resistance, and the marriage of Mark who “was hung in chains.” As always, please don’t forget to SHARE Open Notebook with others! - Wayne

Massachusetts Residents in the Book of Negroes

Eleven Names readers know that many enslaved and free Black, mixed, and native peoples fought in the Continental Army and local militias during the revolution.

Less frequently discussed in terms of Massachusetts but written about often since the release of the 1619 Project is Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775, which promised freedom for any enslaved person who presented himself for service in His Majesty’s troops. While more than 5,000 soldiers of color fought for the Patriot cause, perhaps twice as many fought for the British. Dubbed “Black Loyalists,” women and children also sought refuge in British-controlled territory.

During the 1783 evacuation of New York City, the last major British stronghold, 219 ships carrying 30,000 loyalists sailed mainly to Nova Scotia, and 10% of those who disembarked were Black.

Three thousand names of those Black folk who fled and were granted their freedom were compiled in NYC by British Gen. Samuel Birch and comprise what is today known as the Book of Negroes.1

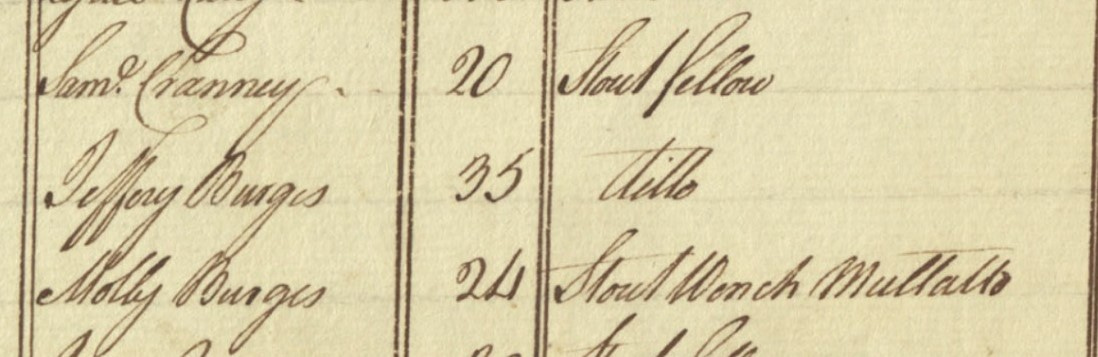

Of those 3,000 people, 30 formerly enslaved individuals hailed from Massachusetts. I’ve compiled the table below from a Library and Archives Canada database. In addition, there’s a link to the Google Sheets version of this table with several relevant links in the caption.

I was intrigued by the listing of “Butter Milk Bay, Massachusetts,” so I decided to see what else could be known about Molly Burges. It turns out Buttermilk Bay is a feature of the larger Buzzards Bay and is surrounded by the towns of Bourne and Wareham. Additionally, there’s a nearby neighborhood in Plymouth called Buttermilk Bay.

It is currently unknown how Molly made her way to NYC, but the Book of Negroes tells us that she self-emancipated circa 1779, and her former enslaver was Nathaniel Ball. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a Nathaniel Ball (or Bell or Beal) in the Plymouth/Bourne area in that period, so Molly’s early life is a further mystery.

On July 31, 1783, Molly was underway on the L’Abondance headed for Port Roseway, Nova Scotia. Listed one row above Molly is Jeffery Burges of Norfolk County, Virginia. I infer from the proximity and having the same last name that the couple is traveling as husband and wife, although I don’t have conclusive proof of marriage.

What we do have are records from the Port Roseway Associates.

During the American Revolution, the British and Loyalist forces evacuated New York in 1783. Hundreds of Loyalist refugees joined as the Port Roseway Associates with the intention of finding new homes and creating a new settlement together in Nova Scotia. These Loyalists, with their families, servants and slaves, founded the community of Port Roseway, shortly renamed Shelburne. The free Blacks amongst the Loyalists formed a separate enclave known as Birchtown.

In Birchtown, named for Gen. Birch, we find a 1784 record of Molly, aged 25, living in the household of Edward Pursley. At the top of the same page, we find Jeffrey Burgess, a sawyer aged 25,2 listed as head of a household with no other members. Perhaps the couple separated, or Molly lived in the Pursley household as a domestic servant so the Burges family could build a better life through a dual income. More research is required to bring Molly Burges’ life into fuller focus.

Although present in Birchtown, Molly and Nathaniel Burges are absent from the names of Black Nova Scotians who migrated to Sierra Leone.

In 1792, 15 ships departed with 1,100 Black Nova Scotians who were promised by the British government large plots of land to colonize a coastal tract of land that is now a section of Sierra Leone’s capital. Much has been written about Settler Town and Freetown, and it’s interesting to note that the number of Nova Scotia settlers in Sierra Leone represents about 1/3 of the number of original refugees from the Book of Negroes.

The Massachusetts connection to this migration is Boston’s Pompey Fleet. Pompey is well known by those who study pre-Revolutionary Boston. Pompey, the son of the very talented enslaved engraver Peter Fleet. Enslaver Thomas Fleet and his sons were printers, and Pompey learned the printing trade alongside his brother Caesar.

Pompey Fleet was on the list of passengers migrating to Sierra Leone. And as Jared Hardesty points out in Black Lands, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England, Pompey Fleet was likely the owner of Sierra Leone’s first printing press that was noted as “in constant operation” in 1794. This may have been the first known printing press in Africa.34

An Act of Resistance on Stonington

The beginning of this Month a large Barn at Stonington was consumed by Fire, together with ten Horses and a yoke of fat Oxen, twelve Ton of Hay, and some Oats: a Negro Boy has confessed he set Fire to it on purpose, because he was tired of tending the Creatures.

From New England to the West Indies, enslaved people injuring or killing draught animals was a common form of resistance. For example, Abington’s Cuffy Rosaria was reputed to have killed and maimed oxen owned by his enslaver Squire Josiah Torrey. In the West Indies, it was common to kill or injure the horses and mules that powered the sugar mills as a way to get a respite from the grueling forced labor that was working enslaved people to literal death. And setting fires was another common act of resistance to enslaved labor throughout the colonies.

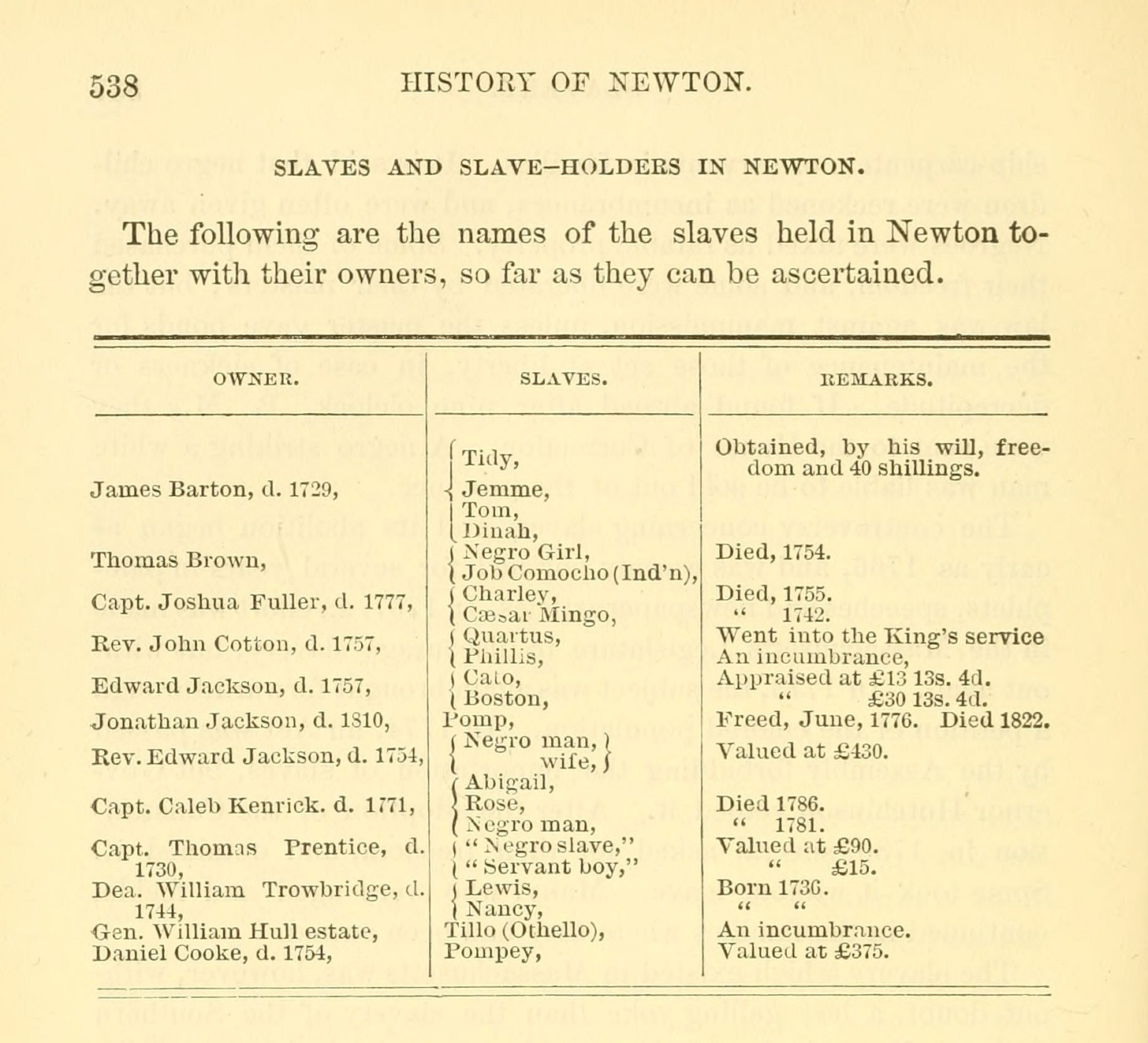

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. John Cotton

The Rev. John Cotton of Newton, Massachusetts, Cotton enslaved at least two people of African descent. This John Cotton appears to be a direct descendent of the Rev. John Cotton, the Puritan minister and grandfather of enslaving minister Cotton Mather. Beyond that, John Cotton seems as boring as one may imagine. Still, the author of an 1880 history of Newton felt compelled to list Cotton among the town’s slaveholders.

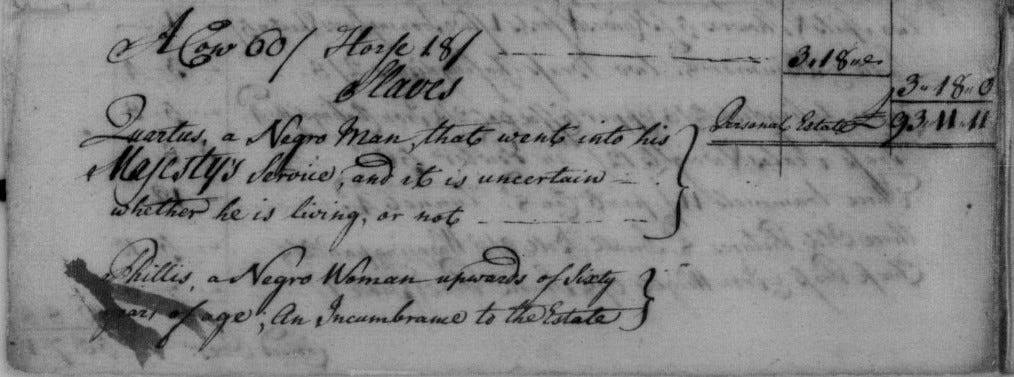

Cotton enslaved Quartus and Phillis. Quartus entered into His Majesty’s Cotton during the French and Indian War (although the estate appraisers didn’t know if Quartus was alive or dead, he was still the property of Cotton’s heirs). At the same time, Phillis, in her sixties, was deemed “an incumbrance to the estate.”

Quartus and Phillis were not the only laborers once bound to Rev. John Cotton— In 1730, we find this ad where Cotton seeks John Waughan, a runaway Irish indenture.

(*NB: We must acknowledge that British colonizers treated the Irish abhorrently, and the indenture system was brutal. But “Irish slavery” is a myth adopted and propagated by white supremacists. Irish servants in colonial New England were not enslaved and did not suffer the racialized chattel slavery for life that Africans and native peoples did.)

Media Recommendation: Paul Revere’s Ride and the Mark of Urban Slavery

I frequently share Old North’s Illuminating the Unseen series, and I hope it doesn’t seem like a crutch. Nonetheless, this is an excellent presentation and there’s a South Shore link to this now-famous story that I want to note below the video.

In this episode of Illuminating the Unseen, Jaimie explores an often-overlooked detail of Paul Revere's ride. In a letter recounting his historic midnight mission on April 18, 1775, Revere mentions that he "passed Charlestown Neck and got nearly opposite of where Mark was hung in chains." Who was Mark and why was he hanged? As you will learn in this video, Mark was an enslaved Black man convicted of poisoning his enslaver, John Codman, in 1755. Jaimie examines Mark's story and its significance to the history of colonial Boston and the American Revolution.

In the vital records of Scituate, we find this marriage intention:

Mark “negro Serve. to John Codmont of Charlestown,” and Ruth Rose, int. Apr. 6, 1745.

I don’t know if the marriage was performed, and I don’t know if Ruth in 1745 was Mark’s Boston wife in 1755. Furthermore, Ruth Rose is a mystery. In these old ‘Vital Records to 1850” books, every marriage is indexed twice, once under the groom’s name and once under the bride’s. Curiously, when this intention is indexed under Ruth’s name, it is not indexed under the segregated “NEGROES” heading where we find the above entry. And the only other genealogical records I can find for women named Ruth Rose around that time all appear to be for white women.

While I wouldn’t read too much into these peculiarities, I bet we will find a fascinating story if we learn more about this record.

Essential Links

Joint Press Release from Harvard University and the Royall House and Slave Quarters, Royall House Facebook page. (HLS pledges $500,000 gift to the Royall House.)

The 1619 Project docuseries premieres today on Hulu. Nikole Hannah-Jones Gets Deeply Personal In 'the 1619 Project' Docu-Series, Ebony

Letter: Slavery & insurrection in NH, The Concord Monitor

NH Highway marker notes former slave who became town’s nurse, WCAX

The story of the Nova Scotia Black Loyalists was adapted as a 2007 novel by Lawrence Hill, which was later adapted into a 2015 miniseries titled The Book of Negroes.

In the Book of Negroes, Jeffery is listed as aged 35.

See: Jared Hardesty. 2019. Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds. (p. 134) In the end notes (p. 168), Hardesty references James W. St. G. Walker (1992) The Black Loyalists, The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783-1870. (p. 204)

For further background on the enslaved Fleet family, consult the scholarly works of Dr. Gloria McCahon Whiting and Dr. Caitlin G. DeAngelis, as well as the public work of J. L. Bell at Boston 1775.