Thank you for reading this week’s Open Notebook. A note: his edition mentions sexual violence. I understand if you want to skip this one. - Wayne

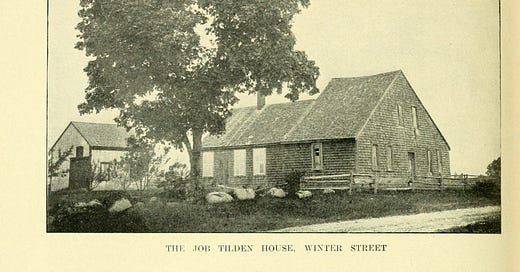

The Job Tilden House

This entry is adapted from my 2022 publication, Slavery in Hanover, Massachusetts, 1727-1783. See also: The Cause of Her Grief: The Rape of a Slave in Early New England by Wendy Warren.

“This house is presented as being especially interesting, because of the fact that slaves were raised here for the market."

Job Tilden held at least six people in slavery at his residence which sat close to today's 325 Winter Street. We can locate this house via Whiting's 1849 "Map of Hanover, Mass." which depicts the house of "Widow Tilden."

Job Tilden was said to have "raised slaves for the market." This was a rare enterprise in New England. What's more, this means that Tilden saw enslaved people as more than just extra hands on the shipyard or as help around the house—he saw enslaved people as capital, a way to store, grow, and transfer wealth.

The obvious question is, how was Tilden planning to "raise slaves?" Did Tilden's plan include rape and involuntary pregnancies? Job Tilden's enterprise recalls English travel diarist John Josselyn's visit to Samuel Maverick on Noddle's Island in Boston Harbor. The year was 1674, and Josselyn noted that an African woman came to the window of the room he was staying in, distressed but speaking a foreign language. When Josselyn inquired with Maverick about the incident, he learned that:

Mr. Maverick was desirous to have a breed of negroes; and therefore seeing she would not yield by persuasions to company with a negro young man, he had in his house, he commanded him, will'd she, nill'd she, to go to bed to her ; which was no sooner done, but she kicked him out again. This she took in high disdain, beyond her slavery, and this was the cause of her grief.

- From John Josselyn, Two Voyages to New England, 1674, quoted in Warren’s The Cause of Her Grief.

Currently, the mechanics of Tilden's scheme are lost to history, and we don't have enough data to evaluate Tilden as a success or a failure. Perhaps there were more than the six known enslaved people at the Job Tilden House. However, if the six people that can be identified are the only enslaved people trapped in Tilden's racket, we find the endeavor wasn't viable as a main source of revenue.

Jack and Bilhah were married by the Rev. Benjamin Bass in 1751 and are perhaps the same Jack and Bilhah later enslaved by foundryman Col. Aaron Hobart of Abington. The only confirmed example of a successful Job Tilden transaction is attested to by a bill of sale detailing Tilden selling a nine-year-old girl named Florrow. This bill of sale is transcribed in the 1921 book Old Scituate. It is unclear if Florrow (perhaps a misspelling of Flora) and the two enslaved children who died at Tilden's House, one in 1754 and the other in 1760, were the children of Jack and Bilhah. And it is unknown if the pregnancies that birthed these children were coerced or forced.

The best-documented enslaved resident of Tilden's house was Cuffee Tilden, a soldier who served with Lt. Job in the Continental Army under Col. John Bailey in the 2nd Mass. Regiment. Cuffee died of disease during the notoriously harsh winter at Valley Forge. It was not unusual for a slaveholder to have garnished the bounty owed to an enslaved soldier for military service; this raises the question of who received Cuffee Tilden's salary and bounty? Was Cuffee able to keep his money come payday, or was Job Tilden paid twice, once for his own service and then again for the use of his property?

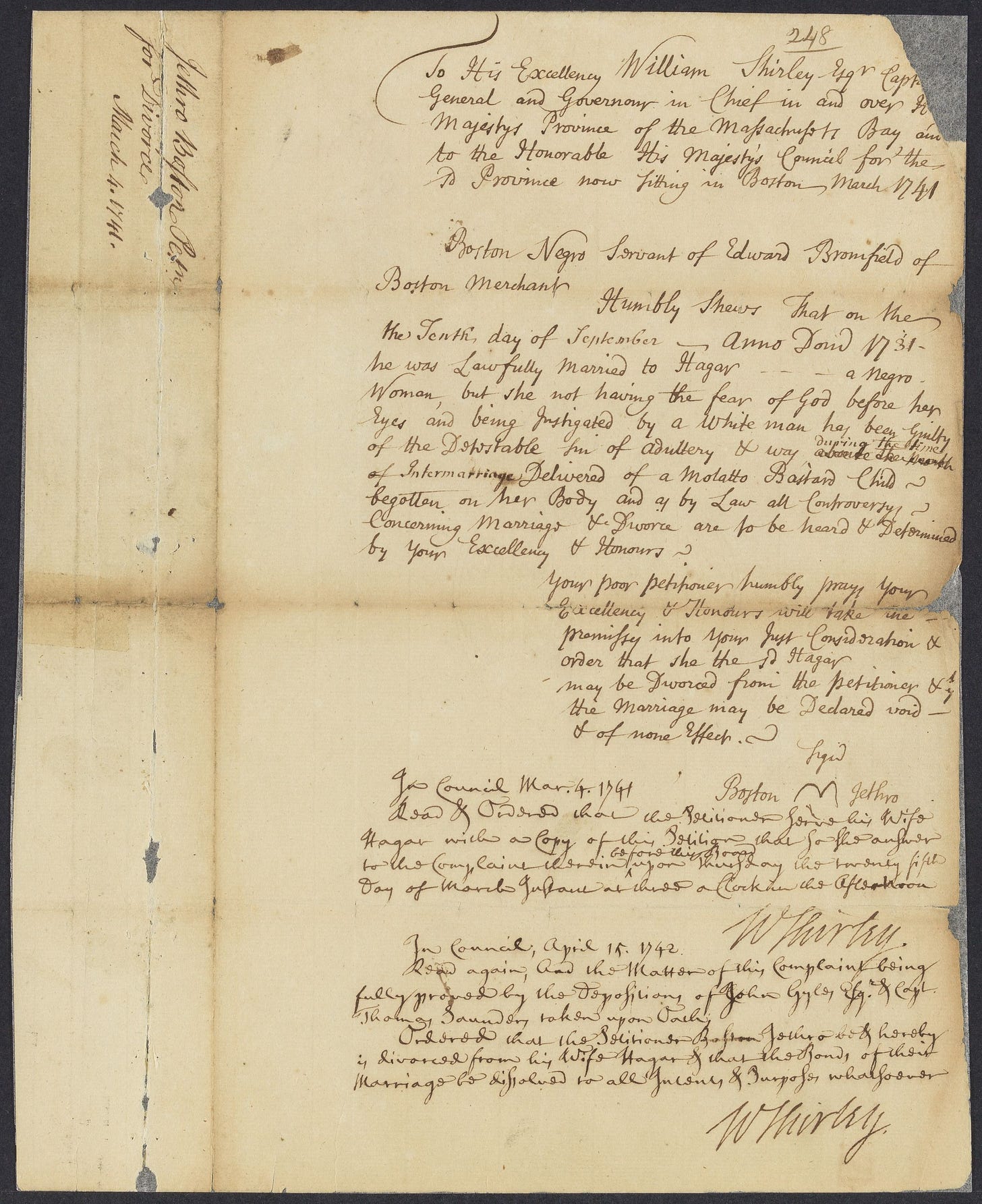

From Antislavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse: Petition of Boston, Negro Servant to Edward Bromfield.

Boston Jethro wanted a divorce.

To His Excellency [Gov.] William Shirley. . .Boston, March 1741. . .

Boston Negro Servant of Edward Bromfield of Boston Merchant, Humbly shows that on the tenth day of September—anno dom 1731-he was lawfully married to Hagar - - - a negro woman, but she not having the fear of God before her eyes and being instigated by a white man she’s been guilty of detestable sin of adultery & was during the time of intermarriage delivered of a mulatto bastard child—begotten of her body and by law all controversy concerning marriage and divorce are to be heard and determined by your Excellency & Honors.

Your poor petitioner humbly prays your Excellency & Honors will take [illegible] previously into your just consideration and order she the said Hagar may be divorced by the petitioner and the marriage may be declared void & of none effect. . .

Gov. Shirley signed off on the divorce on April 15, 1742.

I must confess that I don’t have smart context for this document—if you do, drop a comment below. But a few details pop out. It seems wild that the governor of a colony needed to sign off on a divorce. On the one hand, it seems even more insane that the governor involved himself in the married life of enslaved people. Conversely, it makes perfect sense that the enslaver class wanted to exert absolute control over every facet of Black peoples’ lives.

Furthermore, “instigated by a white man” is one hell of a euphemism. What degree of culpability does this man hold? Did the man assault Hagar? Did the man manipulate Hagar into consenting? Or was this a fling that Hagar entered into of her own volition? And was this man ordered to pay to support the child?

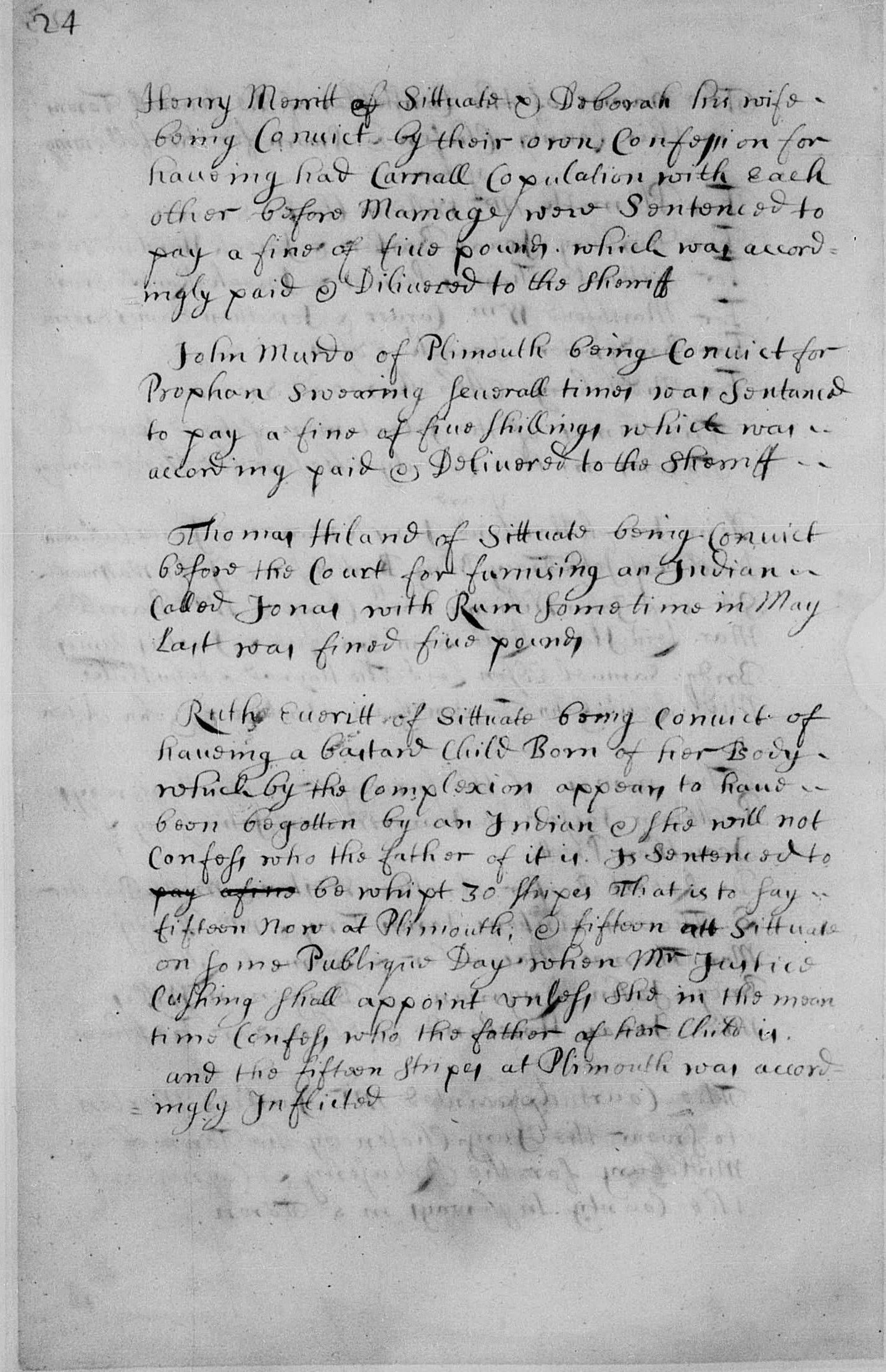

From Plymouth County Courts: Ruth Burrill’s child

I found this 1686 court extract while looking for something else. I share it today because it fits the theme of the dangers and abuses women in colonial Massachusetts endured. White woman Ruth Burrill faced a corporal punishment sentence for a sexual relationship assumed to be with an Indian man, and her child is now in the vulnerable position of being labeled both a “bastard” and “mulatto,” an offensive term applied to people of mixed race. Note that the option to pay a fine was crossed out; my guess is that no man in her family had the grace to step up and pay for her, but it’s possible the judge just wanted to be cruel.

Ruth Burrill of Sittuate being convict of having a bastard child born of her body such by the complexion appears to have been begotten by an Indian & she will not confess who the father of it is. & is sentenced to

payfinesbe whipt 30 stripes that is to say 15 now at Plymouth & 15 att Sittuate on going publique day when Mr Justice Cushing unless she in this moon time confess who the father of that child is and the 15 stripes at Plymouth was accordingly afflicted.

Enslaving Minister of the Week: Rev. Jonas Meriam

“Finding Pamela” is one of New England's most excellent digital humanities projects concerning enslaved life. This exhibit probing the life of Pamela Sparhawk is engaging and pleasing to the eye, and I am in awe because it’s beyond my capabilities. I hope local historical organizations will find grant money (or talented technical & artistic volunteers) to embrace this visual storytelling style for hard histories.

Jerusha Fitch Meriam died in January of 1776, but her death did not bring freedom for Pamela. Mrs. Meriam’s will, made out the previous year, bequeathed Pamela to her husband. Pamela’s enslavement in the Newton parsonage would continue, and when the Rev. Meriam remarried the next year, Pamela would again have done the cooking, cleaning, and sewing to prepare. She was there, too, when the Rev. Meriam’s son Nathaniel died in 1777, maintaining the household through the family’s mourning.

This exhibit was designed and narrated by Cynthia Cowan. Click the image to view Finding Pamela, or follow the link here.

Media Recommendation

Along with the previously recommended book Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery, New England Bound by Wendy Warren are the most instructive texts concerning seventeenth-century slavery in Massachusetts and New England. Get a preview with this episode of Dr. Liz Covart’s Ben Franklin’s World:

Wendy Warren, an Assistant Professor of History at Princeton University and author of the Pulitzer Prize-finalist book New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America, joins us to explore why New Englanders practiced slavery and just how far back the region’s slave past goes.

As we investigate New England’s slave past, Wendy reveals the origins of the African slave trade and why American colonists preferred enslaved labor to free labor; When and how New England adopted the practice of slavery; And, details about how enslaved people lived and worked in early New England.