Gender Nonconformity as Resistance to Slavery

Issue 10: Betty Cooper, Dill Oxford and Illustrating Hard Histories

Welcome, readers. Did you know this newsletter is easily forwarded or shared on social channels? Personalized recommendations are the best way to keep Open Notebook growing. Thank you. - Wayne

Miss Betty Cooper

Today we’re going to examine two Massachusetts gender non-conformists during the time of slavery.

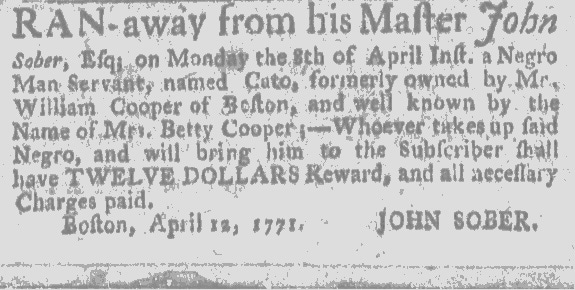

The first example is Betty Cooper of Boston. Dr. Caitlin G. DeAngelis first alerted me to Betty on Twitter, and her article in Notches is our best resource on Betty’s life. DeAngelis points us to a runaway ad that discloses Betty was given the male name Cato at birth.

RAN away from his Master John Sober, Esq; on Monday the 8th of April Inst. a Negro Man Servant, named Cato, formerly owned by Mr. William Cooper of Boston, and well known by the Name of Miss Betty Cooper; — Whoever takes up said Negro, and will bring him to the Subscriber shall have TWELVE DOLLARS Reward, and all necessary Charges Paid. JOHN SOBER, Boston, April 12, 1771.

In her analysis, DeAngelis notes that Betty’s “erstwhile enslaver, William Cooper, was a respected member of the city’s Sons of Liberty,” and the advertisement that Cooper took out suggests “a gender expression that resisted the binary, body-based categories of European colonizers.” Dr. DeAngelis provides further historical context, noting:

Many enslaved people were born into societies whose gender categories did not match European expectations. Captives brought this diversity with them through the Middle Passage, and colonial records everywhere from the Portuguese Inquisition in the sixteenth century to the New York City trial of Peter Sewally/Mary Jones in 1836 preserve partial stories of African-descended people who transgressed Euro-American gender boundaries in ways that can be understood both within a larger transgender history and in the specific context of Black resistance to colonizer’s ideas about gender.

Please visit “Well Known as Miss Betty Cooper”: Gender Expression in 18th-Century Boston (Nov. 28, 2018) in Notches for the full article.

Dill Oxford

“She was highly esteemed in the family and neighborhood. Her rig was peculiarly hermaphroditical — wearing a skirt or petticoat like a female, and a coat after the fashion of a man. Such was her ordinary and holiday appearance.”

Dill Oxford expressed resistance through both gender nonconformity and fashion. She is mentioned in two separate antique histories of the Massachusetts town of Marlborough, which note both her popularity and her androgyny. In a 1910 volume, readers learn:

In 1777, before Rev. Mr. Smith1 was dismissed, he sold a negro servant or slave, Dill Oxford, to Joseph Howe Sr., for 66 pounds. The Constitution of 1780 made all such persons free. Dill, from choice remained in the family of father and son till the day of her death. She was highly esteemed in the family and neighborhood. She always attended the trainings and musters and was very popular with both boys and girls, being always very generous in the handing around of pepper mints and gingerbread. Wearing a gown and petticoat, with a man's hat, coat and boots she made a queer appearance stalking up the streets.2

And found in a 1862 history, we see:

She was highly esteemed in the family and neighborhood. Her rig was peculiarly hermaphroditical — wearing a skirt or petticoat like a female, and a coat after the fashion of a man. Such was her ordinary and holiday appearance.3

A close read hints that the second quote may be one source of the first, or perhaps they’re both plagiarizing from a third source, but I enjoyed the two interpretations of Dill’s personal style.

We must note that affectionate writing about “beloved” enslaved people and servants who "choose" to stay with enslaving families is often wielded as a cudgel of whitewashing. Still, with that in mind and acknowledging that even earnest reminiscences of enslaved companions obscure the cruelty of slavery and its aftermath,4 it's still credible to me that Dill was well-liked by both the Howe family and her neighbors.

Additional insight into Dill’s life is gained through Marlborough’s vital records. In 1766 we find an entry noting, “Dill, ch[ild] Oxford, bap[tized] June 29, 1766. . .[Negro.]” So Dill (a shortened version of the archaic name Deliverance) carried her father’s first name as her surname. Assuming she was baptized close to her birth, Dill was approximately 11 years old when the Rev. Aaron Smith sold her into the Howe household. We also learn that Dill’s father was baptized as an adult in 1762 while enslaved by Mr. Speakman and that Dill had an older sibling, Daphne. It’s unclear if Daphne survived and grew up in proximity to Dill. Furthermore, Dill’s unrecorded mother could have been enslaved by several local white families, but it’s not unfair to speculate that she was enslaved by Rev. Smith, and that is why Dill was his to “dispose of” in 1777.

As I mentioned while highlighting Susan Elliott’s story about Hagar in the second edition of this newsletter, I feel limited in my storytelling because the images I offer readers are restricted to old documents or photos of slaveholders’ headstones. Whether in education or culture, we’re bombarded with images of Pilgrims and Puritans, Salem “witches” and their accusers, and Minutemen and Red Coats. It’s easy to imagine white people in colonial New England. Yet, it is so hard for us to wrap our brains around the profound yet mundane existence of the enslaved and free Black, Indian, and mixed-race population in colonial Massachusetts because they are not represented in visual arts and illustrations. I hope we change that.

And Marek Bennett agrees. Bennett is an independent illustrator, musician, and educator in Henniker, New Hampshire, whose smash-hit The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby graphic novel series will publish Vol. 3 (1864) later this month. From Bennett’s website we learn:

Marek Bennett’s historical graphic novel series details the adventures of NH school teacher Freeman Colby & several contemporaries in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. Drawn entirely from primary source accounts, it portrays the day-to-day realities faced by a diverse cast of participants between 1861-1865.

Bennett also illustrated a compelling comic dedicated to formerly enslaved Massachusetts Revolutionary War soldier Jeremiah Crocker who removed to Henniker after the war and whose headstone stands out in a Henniker cemetery. The comic featuring Pvt. Crocker is available via Bennett’s Patreon site. This is a wonderful comic because it expresses artistically both Crocker’s life and Bennett’s journey in peeling back Crocker’s story; Bennett’s incredulity mirrors my own—wait, slavery in New England? Black Revolutionary soldiers?—and I imagine many Open Notebook readers can relate.

The Surprising Survival of Dill Oxford

This is cool.

Sampled towards the top is Marek Bennett’s Dill Oxford comic panel which blends historical text with his illustrations. The whole panel is lovely, and I hope you’ve already clicked through the link to read it.

Below is Bennett’s live-draw session where he brings Dill’s story to life. During pandemic isolation, Bennett connected with his community through video by providing step-by-step insight into his process of blending local historical texts with original illustrations.

I’m compelled by creative processes even though I’m not a visual artist. I am unlikely to draw my own characters, but I watched Bennett’s video with the same curiosity that I watch cooking shows while eating frozen dinners. Observing the process is enlightening, and viewers can pick up techniques that can be applied to other creative activities.

Also, this should serve as inspiration to young and aspiring local artists: sequestered in the antiquarian histories and hometown archives of New England are a plethora of compelling and astounding under-told stories that, if told visually, will reach a much broader audience than Substack newsletters and WordPress essays ever will.

Create visual art pieces that tell local hard histories!

Find Marek:

MarekBennett.com

at Patreon

at YouTube

Who were the Bucks of America?

This week’s media recommendation comes from the Object of History podcast from the Massachusetts Historical Society.

In this episode, we closely examine one of the most noteworthy items in the MHS collection: the Bucks of America flag. The flag is one of the only remaining artifacts of the Bucks of America, an African American militia based in Boston during the Revolutionary era. There is very little known about the unit with no official military record of their service. We discuss the few pieces of evidence that we have including the flag presented by Governor John Hancock after the end of the Revolutionary War.

This podcast was linked two newsletters back, but I wanted to make sure it received the highlight that it deserved.

Post Script: Haitian Independence Day

Sunday, January 1, was celebrated as Haitian Independence Day. It commemorates the 1804 proclamation of the Haitian Declaration of Independence and the end of the Haitian Revolution, the world’s first successful slave rebellion, and the formation of the world’s first Black republic.

Last May I wrote about one remarkable man who had a front-row seat:

Deyaha Moussa was a Muslim kidnapped in West Africa, purchased in Saint-Domingue by T.H. Perkins of the eponymous School for the Blind, and who witnessed the Haitian Revolution combust. Perkins’ brother trafficked Moussa to Boston in 1793. He died in 1831 and now rests anonymously in Mattapan under a giant Celtic cross.

It’s a compelling story that you can read in full at The Bay State Banner. And when you’re done, check back to Open Notebook issue # 4, for an Update on Deyaha Moussa.

Enslaving Minister of the Week: The Rev. Aaron Smith

Bigelow, E. A. (1910). Historical reminiscences of the early times in Marlborough, Massachusetts, and prominent events from 1860 to 1910. . . p. 299.

Hudson, C., Allen, J. (1862). History of the town of Marlborough. . . p. 396

See: Open Notebook, November 7, 2022, for a discussion on Abigail Adams and Phoebe Abdee.